It’s a Thursday morning, and the band room at White Station Middle School is filling up fast. “Look, a baby bass,” one young player shouts, joyously embracing a new smaller-sized upright and plucking strings up and down the neck.

“It’s adorable,” another student squeals, and an admiring crowd gathers round. The classroom starts to hum with conversation and the sound of instruments coming out of their cases. In an instant, the practice space is too full to navigate easily, which means it’s time for orchestra director Kristi Harrington to raise her baton and start the class.

Harrington is a challenging director, pushing her sixth-, seventh-, and eighth-grade students to play music at a high school level. While Harrington works on a Beethoven piece with most of her orchestra, Marisa Polesky, a first-chair violinist for the Memphis Symphony Orchestra, takes a smaller group of string players out into the hall.

Polesky is one of the Memphis Music Initiative’s 33 music-in-school fellows. Her presence has made it possible for White Station’s students to explore chamber music. She works with several small performance ensembles within the orchestra, giving them the tools they need to work autonomously, leading their own rehearsals without the aid of a conductor.

“Working in small groups and working independently is a really big deal,” Harrington says. “It helps the orchestra, because when the players come back together as a group, they’re better listeners. It improves every aspect of their playing and adds an extra layer to what we do.”

“What did everybody think about that piece we just played,” Polesky asks her students after a solid first run-through of a potential performance piece. The unanimous answer from her students: “It’s too easy!”

Memphis Music Initiative founder Darren Isom asks a radical question about music education: “How do we make sure music is seen as a fundamental part of a proper educational experience for kids?” The question is radical because it cuts hard against the not-for-profit grain, and decades of research justifying art in schools only by showing some measurable relationship between arts engagement and improved test scores in reading, math, and other core subjects.

“There’s a lot of research on that topic,” Isom allows, in his prelude to a more direct thesis. “What we’re saying is this: Music engagement itself is valuable enough.”

The Memphis Music Initiative (MMI) is a grant-making organization that’s grown up inside of ArtsMemphis but is slated to become an independent entity in January. The anonymously funded art and artist-forward program pays a diverse team of Memphis rockers, songwriters, hip-hop producers, sidemen, soulsters, and symphony players a living wage to stay in Memphis, make music here, and work with MMI to enhance school music programs, while connecting young players to regional institutions and the broader Memphis music community.

This isn’t some proposed magic bullet aimed at improving ACT scores. MMI’s teaching fellows aren’t evangelists for any special music curriculum or style of learning. Instead, the program hires artists already active in the community and matches individual personalities and skill sets with teacher interest and the unique needs of participating school programs.

MMI’s director of in-school programs, Lecolion Washington, describes the matching process as a cross between speed dating and a fraternity/sorority bid night. The teachers pick their fellows, the fellows pick their teachers, and everybody works together with a team of MMI coaches to create dynamic teaching opportunities for music programs of every shape and size.

In addition to having a fellow in the classroom year round, MMI also creates field trips and clinic opportunities for the schools it partners with. This semester, for example, Harrington’s classically oriented students will take a workshop with country fiddler Ryan Joseph, best known for his work with Grammy winner Alan Jackson. The aim is to create as many connections and experiences as possible.

“Last year we went to see New Ballet Ensemble’s Nut ReMix,” Harrington says. She thought her players could learn from the Memphis company’s Tchaikovsky redux, with its updated music and fusion of ballet, modern, world, and urban dance. “MMI opens doors that might not otherwise be there.”

Opening doors is something Shayla Jones is interested in doing a lot more of. “I’m a trumpet player. That’s my profession,” she says. “And I’m a vocalist, too.”

Jones learned how to play at Memphis’ Overton High School, where she graduated in 2006. “That experience shaped my whole future,” she says. “And I don’t have any other formal training.”

Jones started working the wedding circuit as a horn player as soon as she graduated. She’s played on cruise ships, been a studio musician, and played with an impressive list of area artists, including Valerie June, Hope Clayburn, and the Bluff City Soul Collective. In college, Jones majored in psychology because she didn’t see a future in music. “I thought I’d keep it as a hobby,” she says. Life had other plans.

Like all the other in-school fellows, Jones teaches 20 hours a week. She splits her time between two schools — the diverse and collegiately oriented Maxine Smith STEAM Academy in Midtown and Memphis Business Academy in North Memphis, where the student body is mostly black and Hispanic.

“The two schools couldn’t be more different,” Jones says. “It’s important for young girls [at both locations] to see what I do,” Jones says. “There aren’t a lot of female trumpet players out there, and I’m successful at what I do, so it’s encouraging.”

Jones shares her professional experiences with students, pulling out her horn, teaching by example, and helping other brass players develop their tone and style. “It’s always encouraging to let them know something is going on in the world outside,” she says.

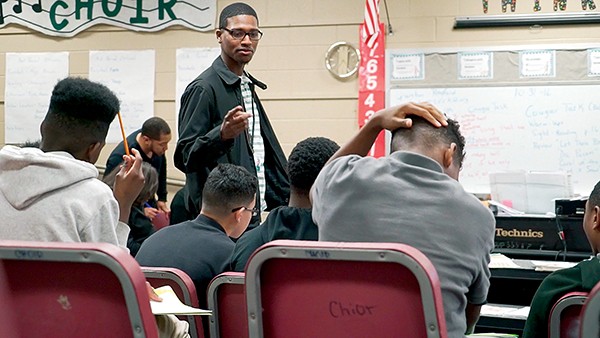

David Roseberry

David Roseberry

One of the things that sets MMI’s music fellows program apart from other engagement programs is the special focus it places on empowering its teaching musicians to be performing musicians. The 20-hour work week is designed specifically to give fellows the time and financial support they need to grow as working artists outside the classroom. MMI makes regular professional development opportunities available, and academic calendars mean summers off, allowing for touring schedules. It also allows musicians who might have chosen to live elsewhere to put down roots in Memphis.

Wes Lebo gets excited by breakthrough moments. “I have this philosophy that music teaches you about life, and life teaches you about music,” he says. The MMI fellow was most recently inspired while working with a young horn player at Ridgeway High School who was more into sports than music. Lebo, who also plays second-chair trombone with the Memphis Symphony Orchestra, remembers singing the melody line, trying to help the young musician develop a better sense of musicality, when the student started singing along. “And he had this beautiful voice,” Lebo says, still amazed. “Kids are usually too intimidated to do that, but he wasn’t. And I couldn’t believe he wasn’t singing in a school or church choir.” The mentor and his student agreed it was something that needed to change.

Lebo’s been playing trombone with the MSO for four seasons, while continuing to perform as a featured player and soloist in orchestras all over the Southeast. Becoming one of Memphis’ music fellows allowed him to move to Memphis and make the city his full-time base of operations.

“I was looking for an opportunity to be based in Memphis and not bounce around,” Lebo says in a phone interview from South Carolina, where he was rehearsing for a weekend gig. “I moved to Memphis this summer, right after I got the phone call. Now I can be there in the city and really be a part of it.”

Washington understands that music can just be a beautiful thing — music for music’s sake — or it can make a statement about the city where it’s being played and the things that city values. Opera Memphis’ recent production of Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro was a collaboration with Washington’s Prizm Chamber Orchestra and inspired by his vision of a cast and crew that are diverse as the city of Memphis. “It was transformative,” says Washington, who founded Prizm in 2005. “Most people could count the number of classical musicians they’ve seen who are black on one hand. And here was an orchestra with 20 people of color. It was special, being able to be around that and having it all be such high quality.”

Washington, who’s been helping Isom develop the MMI’s fellows program since before the pilot launch in 2014, wants MMI to facilitate more transformational experiences.

“We looked at other teaching artist programs,” he says. “But we wanted to innovate. We wanted to make something that uniquely speaks to the musicians we have in Memphis, the students we have in Memphis, and the schools we have in Memphis.”

Culture Club

Memphis Music Initiative Founder Darren Isom is a seventh-generation New Orleans native who took his schooling on the East Coast, got his start in not-for-profit consulting in San Francisco, and came to Memphis three years ago to work with ArtsMemphis in developing engagement strategies.

Darius Williams

Darius Williams

Darren Isom

Memphis Flyer : Let’s start by talking origin stories. What inspired MMI and the fellows program?

Darren Isom : I joke all the time that arts engagement is a euphemism for helping a white organization talk to black people. It wasn’t any different in Memphis. Memphis is a phenomenally interesting city. It’s a city with an extremely vibrant music and arts culture. It’s also a city that’s controlled by a small percentage of the population that lives out in East Memphis who don’t always know what makes the city interesting. So they’re still peddling what was important 30 years ago, 40 years ago. So you have cultural gatekeepers who don’t know what culture they should be keeping the gate on.

How do you shake that paradigm up?

This work became about making sure that the true cultural makers in the city — which often come from the poor black and brown populations — get the attention and support they need and don’t suffer from the same kind of generational starvation cycle that we’ve offered black and brown organizations in black and brown cities that deal with segregation. That work went really well, and, coming out of that work, a set of funders said, “We’re a music city with a music legacy. How do we make sure we position music in a way that it can be used to drive youth and music outcomes? How do we make that happen?”

And that’s when you were asked to stay on and develop the MMI project?

I did a six-month project working with consultants in New York, San Francisco, Oakland, New Orleans, and Memphis, and put together a strategy. And if there are any nuggets or gems that stick, it’s this: I remember doing an interview with a grandmother who lived out in South Memphis. As someone who does engagement, you ask things like, “Why haven’t you visited this institution that’s here for you?” “What are the barriers there, etc?”

I’m used to hearing the same three answers: “It’s too far away,” which is a geographic issue. “It’s expensive,” which is a cost issue, and, “I’m not sure what they’re doing,” which is a relevance issue.

You see this in every city, and for each of those answers, there are workable solutions. As I was getting ready to leave — and maybe she offered this to me because I was a black consultant asking something she’s never been asked by a black consultant — she says, “And you know that place isn’t for us anyways.”

That was the first time I’d heard anybody articulate this concept of something not being for them. I’m a black guy from a black city. I know what that means. That means you can offer a bus. You can make it free. You can even put up an installation about me and my culture, but ultimately you really don’t want me there. That’s the baggage of segregation.

How do you overcome things like that?

The work became making things that people see as being for them. That’s theirs. They aren’t being invited, they own it. That became the Memphis Music Initiative.

The idea that music education is enough sounds almost radical when you say it out loud.

I joke sometimes that in New Orleans, after Katrina, they put music in the schools so kids would come back.

There’s value to giving students things that make them look forward to school.

Exactly. That counts for something. Second, the goal was to have music fellows who were coming from different backgrounds. Whatever you do, if it’s musical, we’re all about it. We wanted to bring these people into the schools and have them support instruction — and not just quality music instruction, but quality mentoring that lets students see what success looks like in life. It’s important, particularly in underserved communities, to position kids as cultural leaders and give them something they can own and be good at, as they struggle with other things. You have to be good at something to struggle with everything else.

The fellows are MMI’s most visible element, but the strategy seems more comprehensive.

We’re a granting organization. And we recognized that outside of school only five percent of kids had access to quality music activities. In other cities like New Orleans and Nashville that number’s closer to 20-25 percent. Children bloom where there’s opportunity, and there’s just a dearth of out-of-school music activities. Underserved communities are where you double down on youth programs, especially after school and in the summer, when kids are likely to lose what they’ve learned or get involved in negative activities.

We work in a grant-making role with groups that are already working with children — groups like Stax Music Academy and the Visible Music College. We want to make it so when you walk into any space created for youth activity, you should be able to engage in a high-quality music-related activity. Because this is Memphis. This should be available at any Boys Club or Girls Club or the YMCA. If you walk into an organization that serves kids, you should have an opportunity to explore music.