courtesy Philip Pearlstein

courtesy Philip Pearlstein

Philip Pearlstein’s Female Model On Bed, Hands Behind Back

Of the roughly 9,000 works in the Brooks Museum collection, only about 3 percent are on display at any given time. Of that displayed 3 percent, fewer than half of those are delicate works on paper that are only allowed (by curatorial dictum) to see the light of day once a decade. A fraction of that fraction are contemporary and modern works on paper.

Courtesy Red Grooms / Artists Rights Society (ARS)

Courtesy Red Grooms / Artists Rights Society (ARS)

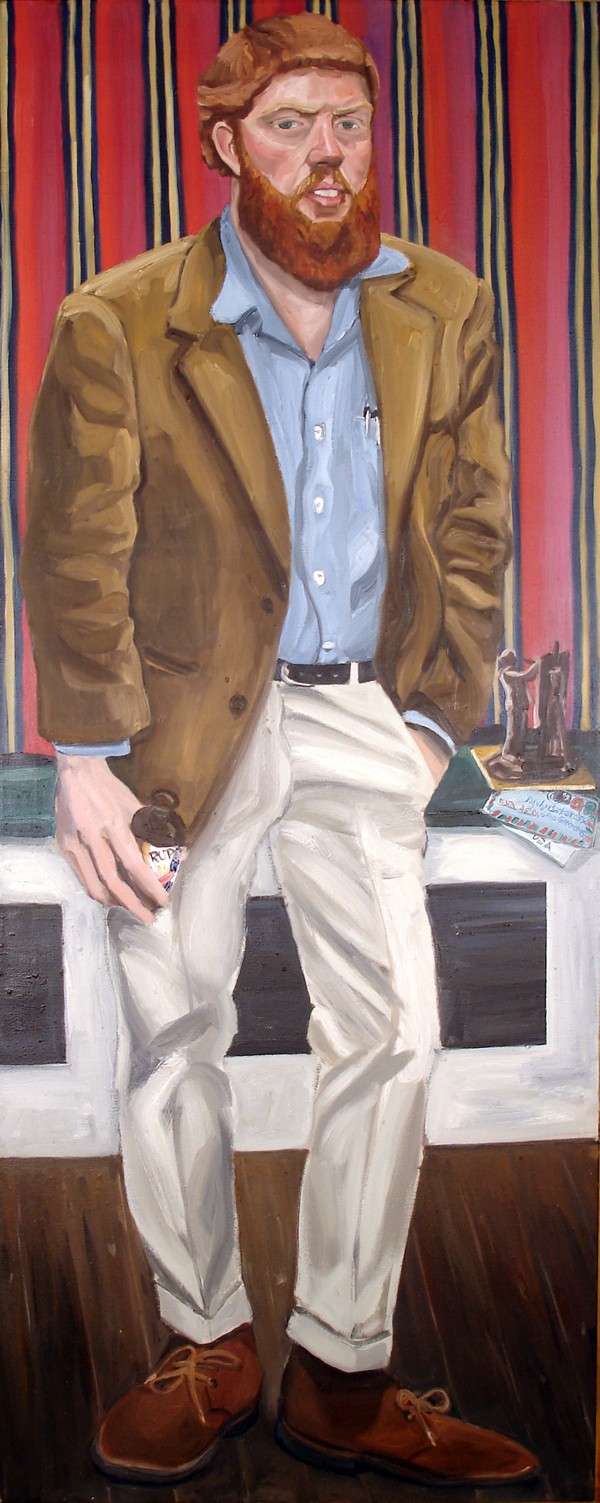

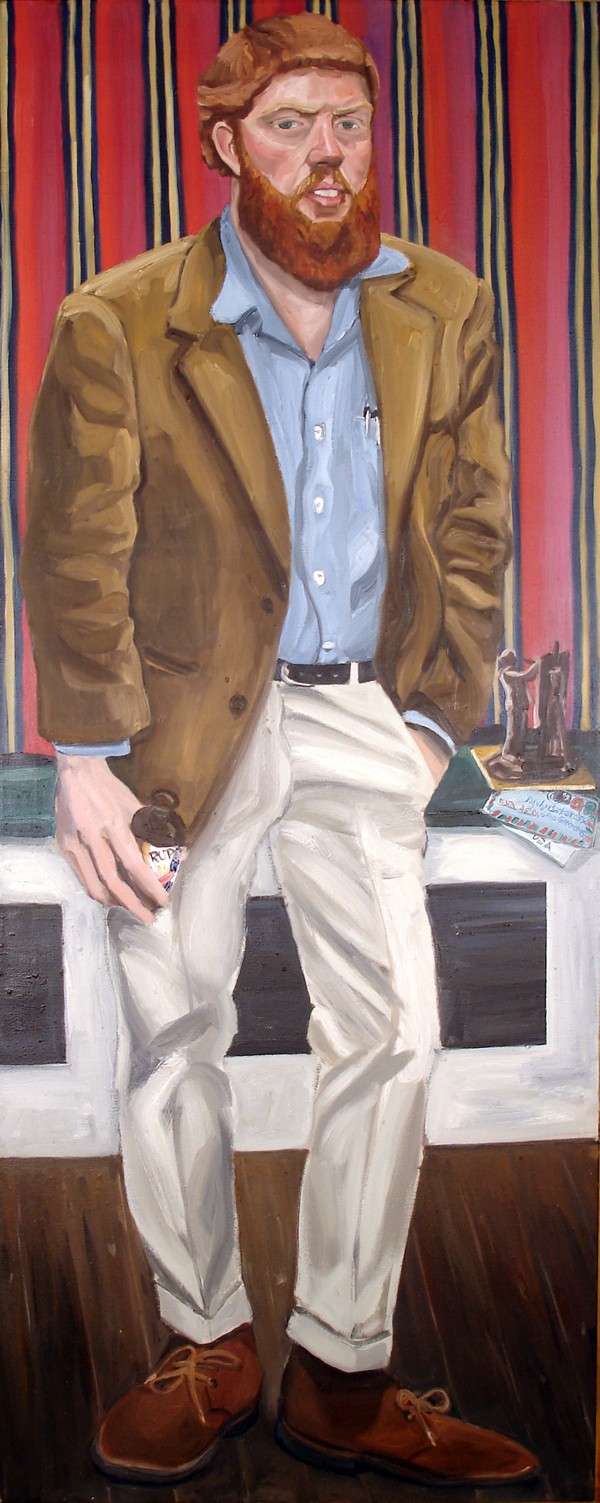

Red Grooms’ Portrait Of Paul Suttman

With this circumstance in mind, you should really make a trip to see the masterful 1973 Philip Pearlstein drawing Female Model on Bed, Hands Behind Back, currently on display in the Brooks exhibition “The Eclectic Sixties.” It is not one of Pearlstein’s more famous works (the artist is better known for his mammoth and psychologically rigorous nude oil paintings), but it is a candid and beautiful example of what simple line work can do to describe the human body.

The Pearlstein drawing, along with other works in the “Sixties” exhibition, is on display through September as part of the Brooks’ summer focus on the decade. “The Eclectic Sixties” and another small show are intended as support for an important retrospective of the works of mid-century artist Marisol, set to open in June. Marisol’s work will dominate the museum’s lower galleries with “The Eclectic Sixties” operating as a descriptive entry-point to the retrospective.

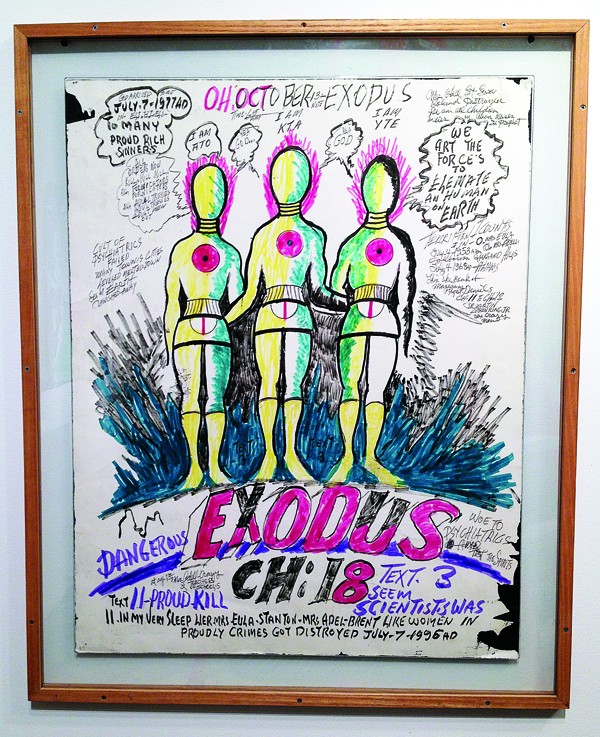

Courtesy Estate of ted faiers

Courtesy Estate of ted faiers

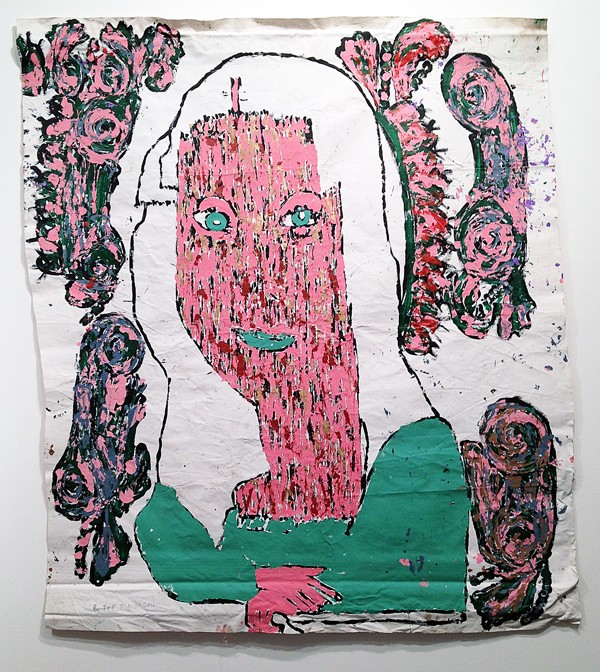

Ted Faiers’ Woman With Cat

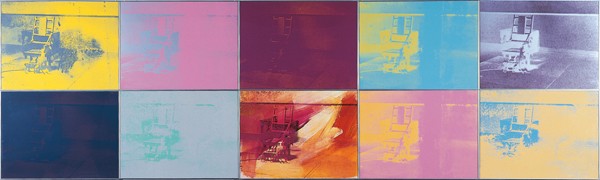

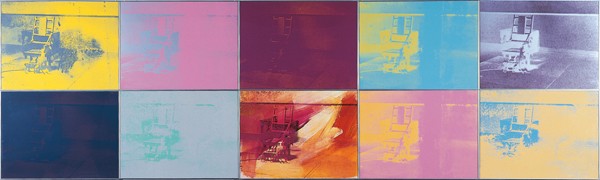

“The Eclectic Sixties” is entirely comprised of works culled from the Brooks’ permanent collection, including a loosely brush-worked portrait of sculptor Paul Suttman by Red Grooms, a 1971 psychedelic bust of a woman holding a cat called Woman With Cat by Memphian Ted Faiers, and a neon Andy Warhol series, “Electric Chair.” There is a cool 1966 “photolithography concertina” — an accordian-style photo book — by Edward Ruscha titled Every Building on Sunset Strip.

Courtesy David Parrish

Courtesy David Parrish

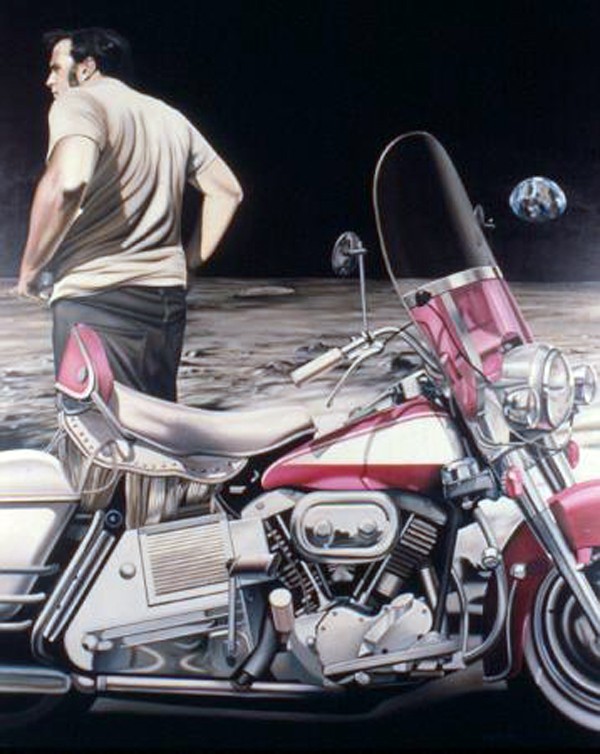

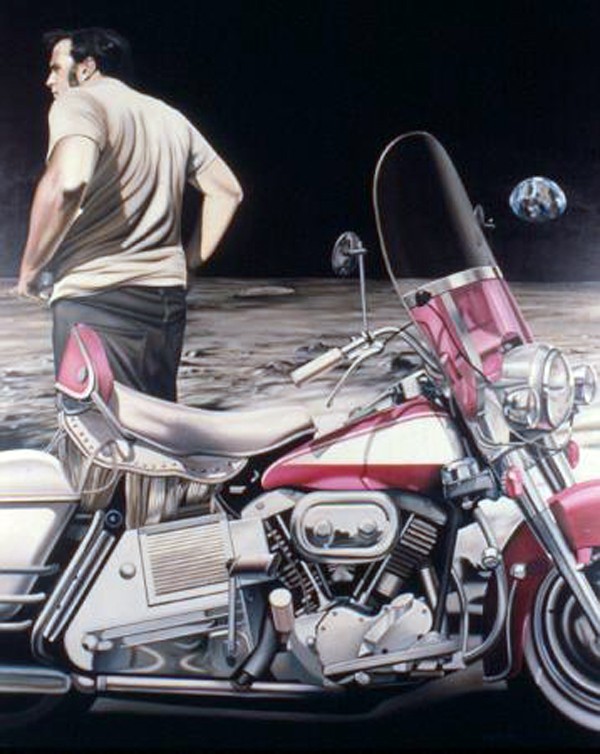

John Parrish’s The Eagle Has Landed

The exhibition is almost evenly divided between collage and assemblage-based works — the sort that might have been made from Alphabet City garbage and old Polaroids — and colorful pieces in the Pop Art canon. Most works are from the ’60s or early ’70s, though a few pieces are from much later and reflect a strong period influence. One of these later works, John Wesley’s 1998 Showgirls, is the purest Pop piece in the entire exhibition; it would be difficult to guess that it was painted 35 years after the peak of the style.

The inclusion of later works and the exhibition’s loose approach to hard genres (Pop! Op! Surrealism! Assemblage! et cetera) is refreshing. Too often, work from the period is curated with stiff reference to over-defined mid-century art movements or with reductive historical explanation about American counterculture and societal shifts. The Brooks exhibition sidesteps that. The works in the show feel intimate, left to their own devices.

Courtesy Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Courtesy Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Andy Warhol’s Electric Chair

The Eagle Has Landed, a large photorealistic oil painting by John Parrish, is the poster-child for the exhibition, not only because it is dominant and flashy (it depicts a greaser with his motorcycle on the moon), but because it brings together many of the other works in the show — it is figurative, accessible, and very human but has a hard-edged chromatic coloration that seems advertising-inspired. The headspace of the painting also seems dead-on: a moon that is a fantasy landscape that is the desert, somewhere between Las Vegas and the stratosphere.

“The Eclectic Sixties” at the Brooks through September 21st.

courtesy Philip Pearlstein

courtesy Philip Pearlstein  Courtesy Red Grooms / Artists Rights Society (ARS)

Courtesy Red Grooms / Artists Rights Society (ARS)  Courtesy Estate of ted faiers

Courtesy Estate of ted faiers  Courtesy David Parrish

Courtesy David Parrish  Courtesy Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Courtesy Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York