“The whole city is a dark closet, with entrapment, harassment, and copying of license plate numbers from cars parked outside bars,” wrote a visitor to Memphis in 1969 — his words meant to shock his audience with the reality lying below the Mason-Dixon line for LGBTQ individuals, even as the effects of the Stonewall Riots ricocheted and spurred the gay liberation movement throughout the nation.

But such a statement would shock no Memphian half a century ago and even today. Just the other week, councilman Edmund Ford Sr. berated Alex Hensley, Shelby County Mayor Lee Harris’ special assistant, for their use of she/they pronouns. A few weeks prior to that, Briarcrest Christian School promoted a class titled “God Made Them Male and Female and That Was Good: a Gospel Response to Culture’s Gender Theory.” Meanwhile, the state of Tennessee actively legislates against trans people, having introduced five anti-trans bills into law this year alone.

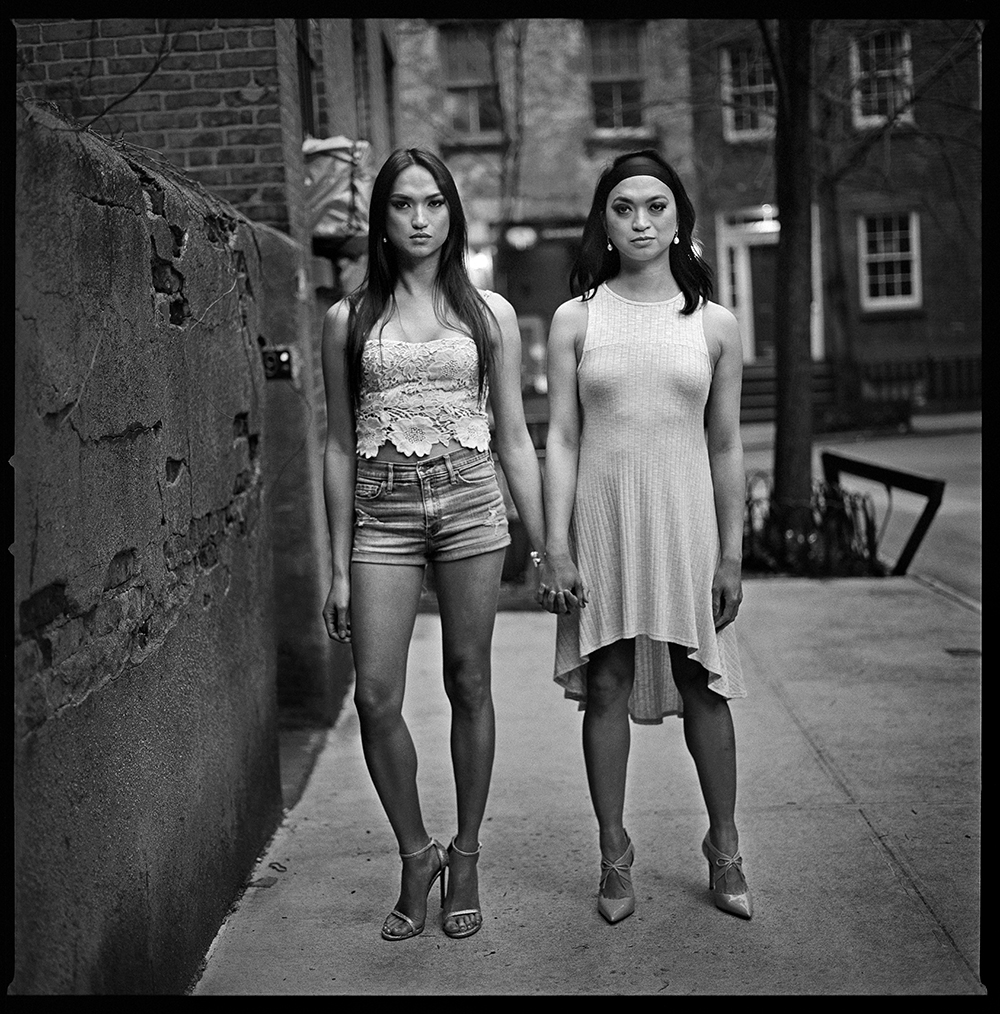

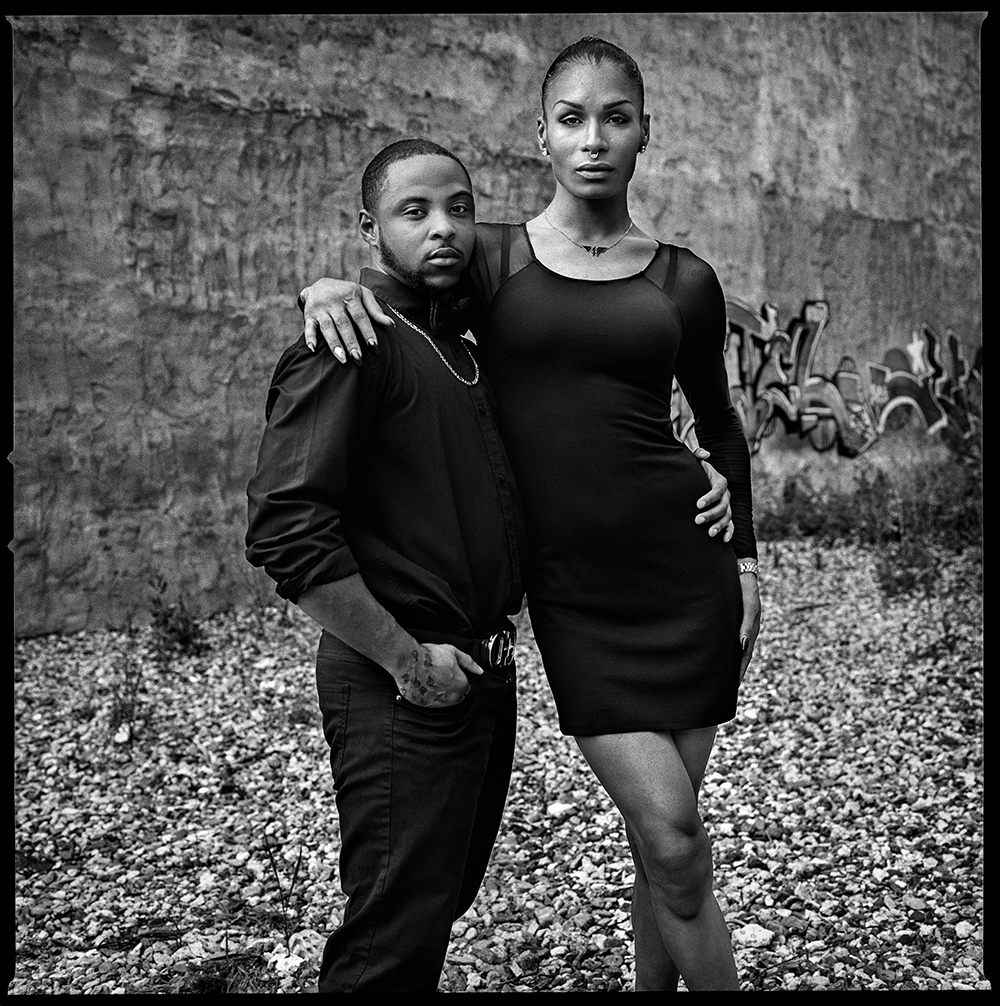

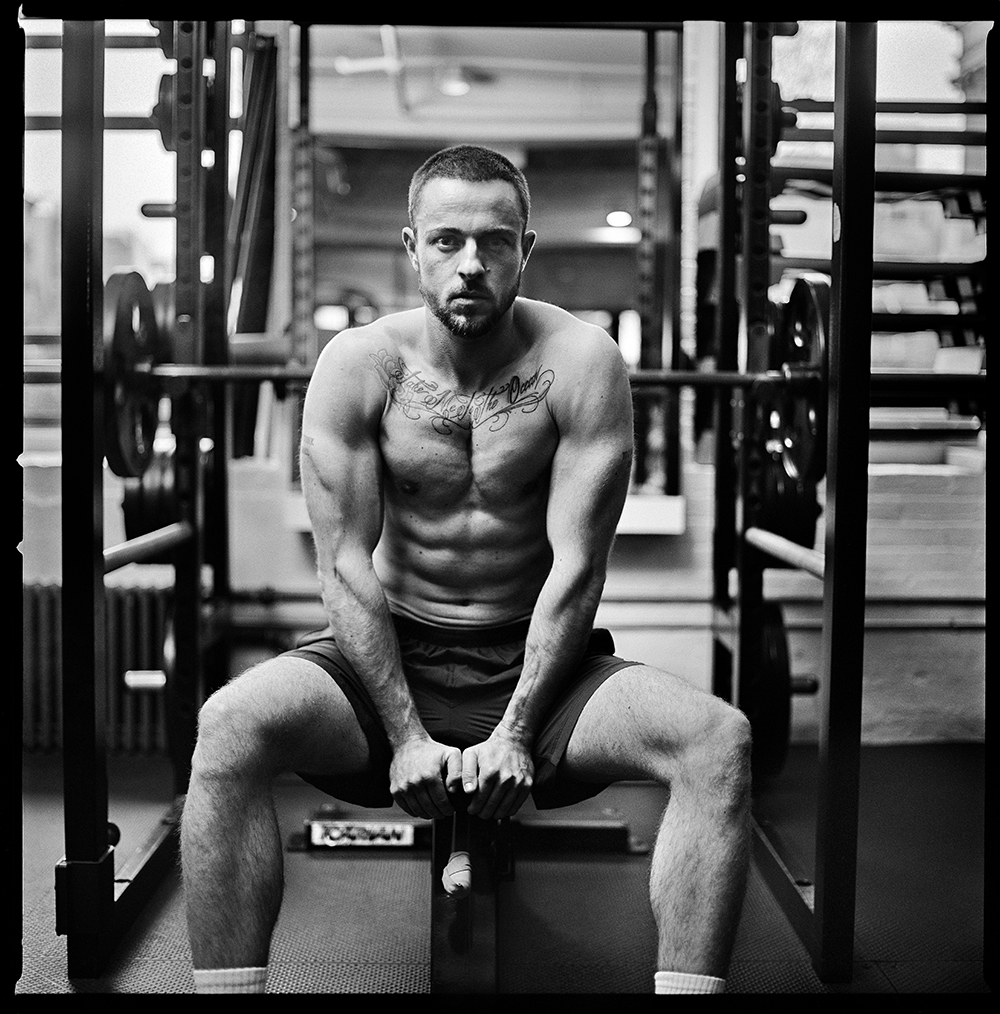

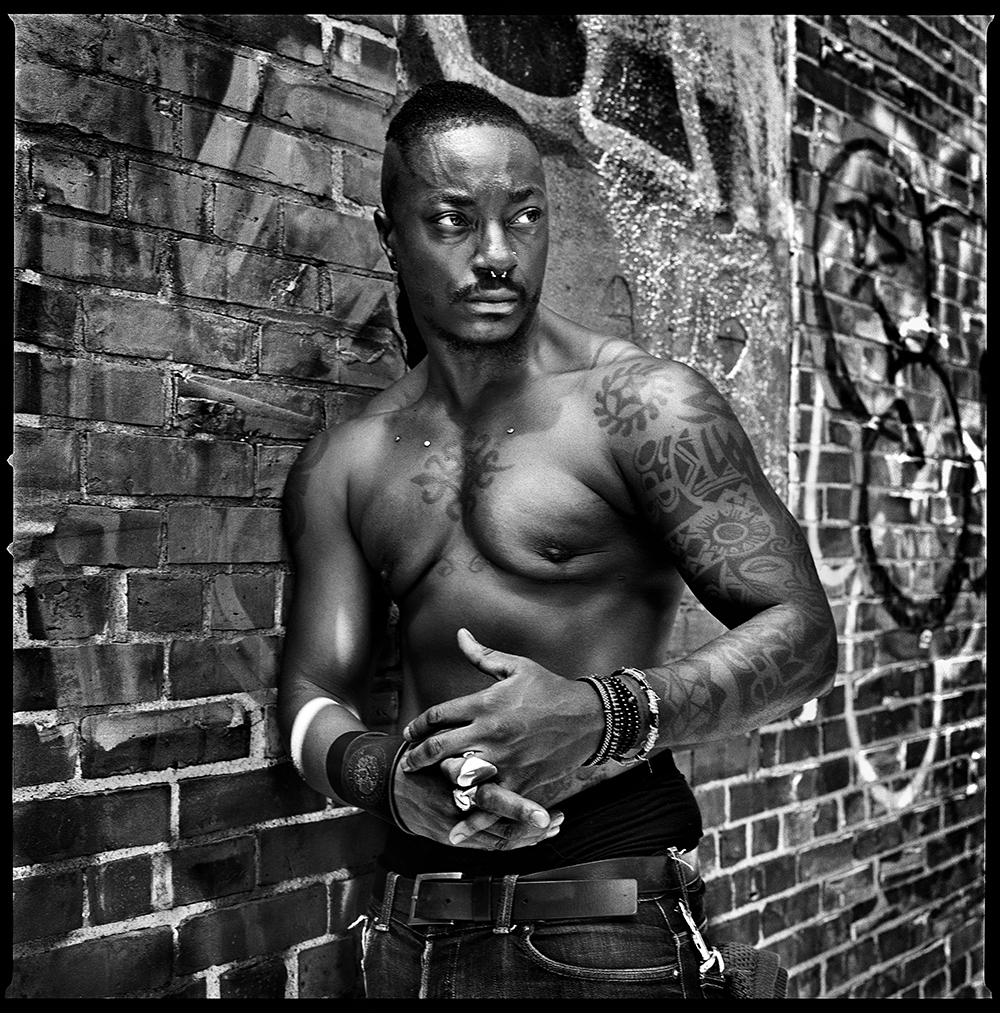

It’s a saddening reality that, even in our blue oasis of a city, transgender — nonbinary and gender diverse — individuals lack the community support and representation they need and deserve. As recently as this September, Memphis witnessed its first trans-focused art exhibition at the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art: “On Christopher Street: Transgender Portraits by Mark Seliger.” Transgender individuals have always been here in Memphis, but this exhibit in 2021 marks the first time they have been truly celebrated in Memphis and the Mid-South by an institution as historically and culturally significant as the Brooks.

Why Christopher Street?

Christopher Street in New York City is home to the Stonewall Inn — the site of the 1969 Stonewall Riots. Today, though, the street that was once sanctuary to queer and trans folk is slowly losing its identity as gentrification seeps in over the city — a sadly familiar phenomenon.

Photographer Mark Seliger noticed this pattern and set out to document the street in 2016 before it completely lost its vibrancy. Seliger, who has photographed for GQ, Vanity Fair, Rolling Stone, to name a few, began this project by photographing people he found interesting along the street. Before long, as he got to know his subjects, particularly his trans subjects, he realized the through-line of his story was not just that of gentrification but that of the trans community.

“Once I started to hear their stories, their struggles and triumphs, it turned into a bigger body of work,” he says. “This was the first time for many of them to be photographed, I think, in what they consider to be their real identity.”

Angelique Piwinski sat for one of the portraits after being connected to Seliger through one of her friends. Piwinski had worked in advertising for 41 years and was an executive vice-president for the last 20 before retiring in 2018. “I had heard of Mark from the ad point of view,” she says. “I’ve never needed portrait stuff done [for myself]. … When they said Mark Seliger is going to shoot it, I was like, what? I was in awe of the guy.

“You look at the photographs; you see the use of lighting. He captured the essence of me in the picture,” she continues. “Is it a glamor shot? No, it’s not the selfie I would take, but I think he captured a certain essence.”

Since retirement, Piwinski has advocated for LGBTQ+ rights and has led diversity and inclusion lectures and trainings in the corporate environment. “If I can change a couple of lives, I’ll be happy doing that — even one life would be a super reward. I’m putting a face to a group of people,” she says. “People need to come into a museum and be comfortable and see themselves somewhere. If you don’t represent as many different types of life stories, you’re going to miss the mark.”

From New York to Memphis

In 2018, Rosamund Garrett, the curator for this exhibition, moved to Memphis from London with her wife Lucy, a photojournalist. “I didn’t know what it was going to be like to be queer in Memphis, and sometimes, I think, the South doesn’t always sound like the friendliest for queer people from the outside,” she says. “But when I came here, I found that there was this very rich and diverse selection of LGBTQ+ cultural organizations and that there are huge numbers of queer and gender-diverse people here. Which was a really wonderful discovery — that I can hold Lucy’s hand in the street.”

But Garrett soon discovered that the Brooks had yet to do an exhibit with an LGBTQ+ focus. “I felt it was a moral imperative to do something,” she says, so she took to searching online for inspiration and found a website that listed Seliger’s collection, which was originally compiled in a book, as being available for exhibition. “It had been listed on the website for several years, and no one in a U.S. art museum had taken it. I was surprised; these photographs are beautiful.”

Curating this exhibit of 34 portraits, Garrett says, has changed the way the museum works. For the first time in its history, the museum formed and paid advisory groups, consisting of local LGBTQ+ organizations and the portrait sitters. “We used their feedback to build everything — to build the interpretation, the labels, the education space that we got in the exhibition, the programming that we got,” Garrett says. “And from this emerged two close community partners, OUTMemphis and My Sistah’s House.”

Alex Hauptman, the transgender services manager at OUTMemphis, was a part of one of these advisory groups. “We talked about what elements could be incorporated into the exhibit to make it feel like it wasn’t exploitive and that there was purpose to the exhibit,” he says. “That was really refreshing. I really appreciate the intentionality, and I think a big piece of that is owed to Dr. Garrett.”

Garrett, however, is humble in that regard. “Although I’m the curator,” she says, “in this sense, it was a lot more like a facilitation role.” Usually, the curator writes all the wall text and the labels, but in this instance, Garrett wrote only the introductory wall text while the labels beside the portraits are in the words of the portrait sitters. “The idea is really for me to melt in the background and to let their voice come through.”

At the exhibit’s entrance, a documentary film featuring several of the portrait sitters plays, giving the viewer a chance to meet the person before seeing their photo. The exhibit also has an accompanying audio tour on SoundCloud, where visitors can hear the portrait sitters’ voices — the inflections, the pauses, the emotions — as they stare directly into the camera lens, directly at the viewer, with an intense vulnerability that begs the observer to listen to their story and take time to witness them as the individuals they are.

“A lot of times the sort of dislike or distrust or gross-out, sideshow factor of the trans community that the mainstream population might have is because they don’t have a close interaction or a close connection to a trans person or the trans community,” Hauptman says. “So like, they only see it on TV or in the punch line on comedy shows, so they only have a very specific lens that they view trans people through that’s not humanizing and usually pretty one-dimensional.

“Part of me just hopes that maybe people who don’t have a lot of exposure to trans folks go to this exhibit and see this human side and read the stories on the walls or even just look at the people in the portraits and make a connection that was missing for them that helps see them as human people,” Hauptman continues. “Trans people have very unique experiences, but they’re still relatable.”

A Beginning

“We’ve thought a lot about the legacy of the show,” Garrett says. “One key part of that is making sure that the trans community is always represented in this museum.” So, to add to the Brooks’ permanent collection, the Hyde Foundation purchased one of Seliger’s portraits — that of ShayGaysia Diamond, a musician who was born in Little Rock, Arkansas, and raised in Memphis.

“That portrait is the first portrait that you’ll see,” Garrett says. “And it’s the first portrait — that we know of — of someone who self-identifies as trans to enter the permanent collection, and since then we’ve bought five historic press photographs of trans women from the ’50s and ’70s, including the American icon Christine Jorgensen and the British equivalent, I would say, April Ashley.” These five photographs are along the exterior wall of the exhibit.

The actual exhibition space isn’t square; the walls are faceted, so the portraits surround the viewer from every angle. “Because of this odd shape,” Garrett says, “it kinda feels like a hug.”

“It’s funny — I’m not an overly emotional person,” Hauptman says. But during opening weekend in mid-September, when he was alone in the exhibit for the first time and surrounded by the portraits, he says, “it just kinda hit me that this is the first time I’ve gone to a legit museum — I’ve been to art shows, galleries, stuff like that — but this was the first time I’ve ever walked into a museum and saw people that had experiences similar to mine that were part of a community that I was a part of, surrounding me on the walls, and celebrated in a way that they were displayed beautifully and with pride.

“It hit me. I can see people who are a part of my community reflected on the walls back at me. I can see different pieces of myself told back to me, which doesn’t happen often in a museum. It was a lot more impactful than I thought it was going to be. I kinda got choked up for a second. I’m 37 years old; trans people have been around for a really long time. It shouldn’t be this big of a deal, but it was. I’m not trying to diminish the exhibit.”

Similarly, Garrett adds, “It’s never enough but it’s the beginning. … Museums reflect the society in which we live, and that’s why they’re not always equitable places. However, museums can also try to help shape the society in which we live because people’s stories, which is culture, can change things like policy by winning over people’s minds and hearts first. Small exhibitions like this can just start to nudge people in a little bit of a kinder, more loving, more respectful direction.”

Before leaving the exhibition space, visitors have the opportunity to write down comments in a spiral notebook stationed near the entrance. Inside it are an overwhelming number of messages of gratitude, from guests young and old, gender-non-conforming and cisgender, thanking the Brooks for their commitment, intentionality, and education behind this exhibit.

Memphis’ Christopher Street

When visiting this exhibition, Garrett encourages the viewer to consider where or what your Christopher Street might be. “To me,” she says, “Memphis is like the Christopher Street of the South. Both places are complicated, but I think Memphis is a beacon in a region that can otherwise be difficult for many communities.”

Like Christopher Street, Memphis is undergoing its own bout of gentrification, making areas that have affordable housing become smaller and smaller, displacing more and more people. “I hope that this show helps people to question who you’re consulting when you’re building,” Garrett says. “Are you bringing the community with you? What are the processes by which we’re evolving our communities? How can you keep what is integral to Memphis?”

Even though he moved to Memphis just under two years ago, Hauptman says, “I can see the economical impact [gentrification] is having. There was already a big gap in socioeconomic stability with the trans community and LGBTQ community; I think it’s driving a wedge, the rent is going up, so the people who were already struggling with rent are struggling more. The housing options are less and less livable.”

As part of his many responsibilities as the transgender services manager at OUTMemphis, Hauptman oversees the nonprofit’s OUTLast Emergency Assistance fund, which provides immediate resources for trans people of color, LGBTQ+ seniors, people living with HIV, and undocumented LGBTQ+ individuals.

“A lot of people in OUTLast are unhoused. They stay in hotels, stay with friends,” he says. “Through the OUTLast program, we see a lot of trans people who don’t have stable housing, don’t have consistent income, aren’t able to get secure jobs, and have to resort to underground economies. There’re a lot of folks who struggle every day here.”

Organizations like OUTMemphis seek to alleviate some of that struggle, and Hauptman also points to My Sistah’s House, run by Kayla Gore, which provides emergency housing for gender-non-conforming people of color. “But there’s never as much resource as there needs to be,” he says.

“Trans people are statistically underemployed,” Hauptman says. “They don’t make as much money as even cis individuals in the LGBTQ community. People don’t want to hire them; they get fired. This is a state that has no gender equality protections for employees so they can be fired for coming out or being trans. They can be discriminated against for housing. They can be denied rental applications for being trans. There are no protections. People can deny them basic opportunities just for being trans.” All this is in addition to the mental health struggles perpetuated by stigma and lack of access to resources — not to mention the rising violence against transgender people. Forbes called 2021 the “deadliest year” for transgender people since records of such violence began.

To shift this narrative, Hauptman encourages people to vote, donate, advocate for trans rights, share information on social media, hire trans people, rent apartments to them, be aware of and correct language and misconceptions. “I do encourage people to do their own education around trans issues. Start in that corner of the museum, where there are educational resources,” Hauptman says. “Look at where you’re at and look at where your power lies and your privilege — how can you use that to help people and make a difference?

“I think, for a lot of people, they might not see the value in a museum doing an exhibit like this,” he continues. “The more spaces that do things like this, that show trans people in a bold, unapologetic way, it helps spread the message that it shouldn’t be a bold move to do this. For the Brooks, it should just be a beautiful portrait exhibit of beautiful people, but we’re not there yet. But the more areas of life in general where we can have the presence, it starts to shift the space in terms of what’s safe.”

“On Christopher Street: Transgender Portraits by Mark Seliger” is on display at the Brooks Museum of Art until January 2, 2022. For more information on the exhibition, visit brooksmuseum.org/christopherstreet. For LGBTQ+ resources, visit outmemphis.org or call 901-278-6422.