Introducing the Justice Project:

Injustice is a problem in Memphis — in its housing, its wealth-gap, its food deserts, its justice system, its education system. In 2018, the Flyer is going to take a hard look at these issues in a series of cover stories we’re calling The Justice Project. The stories will focus on reviewing injustice in its many forms here and exploring what, if anything, is being done — or can be done — to remedy the problems.

– – – – –

Sometimes the Memphis City Council works behind the public’s back.

For example, the maneuvering behind its most controversial decision last year — removing Confederate statues from public parks — was kept secret from Memphis citizens until after the decision was made. The council created a new rule, written vaguely and broadly, and ushered it through a months-long legislative process, with plenty of debate and public input. Then, at the last second, they erased the whole thing and filled it in with details they did not think the public needed to know until after the fact of its passage.

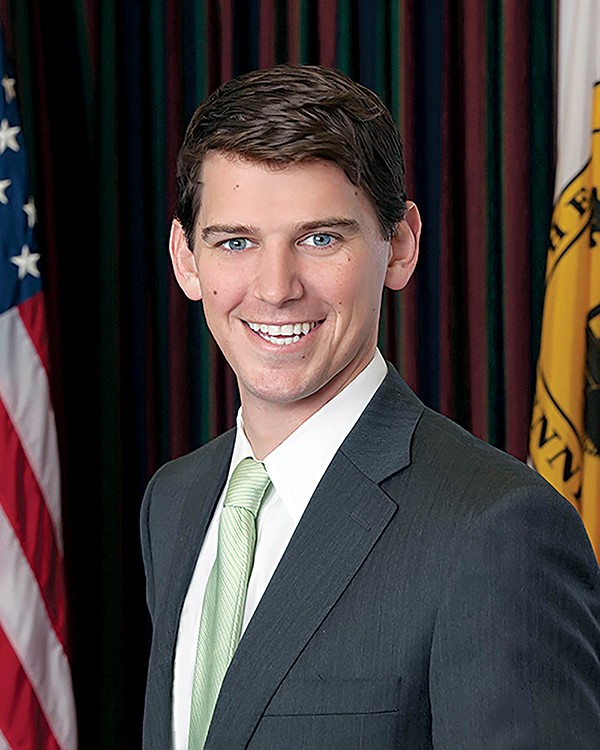

Council members say the move was legal and that they’ve used the same ploy in the past. Council member Worth Morgan, for one, said he “certainly won’t apologize” for using the maneuver on the statues vote. What we’re left with — the council and the public — is a legislative sleight of hand that allows local government to make decisions without public knowledge or input.

Council member Worth Morgan, for one, said he “certainly won’t apologize” for using the maneuver on the statues vote.

Another example of a council end-around occurred when the public was not informed about a firm the council hired to lobby in Nashville. They spent $120,000 of taxpayer money to urge Tennessee state lawmakers to kill Instant Runoff Voting, a measure approved by Memphis voters in a referendum 10 years ago. When asked about that decision, council attorney Allen Wade was quoted in The Commercial Appeal as saying that the council uses taxpayer dollars “to do a lot of things” people don’t like.

In a third example, council members sometimes introduce last-minute resolutions and ordinances that hinder public involvement.

All of this may be perfectly legal. But is it right? Do Memphis taxpayers and voters deserve more transparency?

At least one council member said that some council processes may need review. But most members defended the moves, citing complicated legislative procedures, overall council prerogatives, and other rationale.

Taken separately, each legislative maneuver seems like an arcane machination of the democracy machine, movements that take access to local government out of the hands of the people who pay the taxes that run local government. Taken together, they seem like parts of a playbook that’s used to cloud the legislative process and keep citizens out of certain conversations at Memphis City Hall.

The Secret Statues Vote

On Wednesday, December 20th, council members settled in behind their microphones to resume a meeting that it had adjourned from its regular Tuesday session the day before. One major question loomed: What would the council do about the Confederate statues in two city parks?

A final vote on the matter was on the council agenda. That item read, simply, “ordinance relative to the immediate removal of the Forrest Equestrian Statue and the Jefferson Davis Statue and other similar property from city owned property.”

Intensity built as the council first worked through some routine business. Tension rose further as three members of the public gave the council their parting thoughts on the statues. Then, when the item came up for that final vote, something confusing happened. At least, it was confusing to the anyone outside city government’s inner circle.

Council member Edmund Ford brought a new rule — a substitute ordinance — to the table that would change everything. The document was not handed out to the public. It was not in the council’s agenda packet, which is public record. The council voted unanimously to accept the new rule. Then, they voted to unanimously approve it, and it was done.

But, as is customary with big votes in the council chamber, not a single member of the audience whooped, cheered, jeered, booed, or hissed. They sat, stunned.

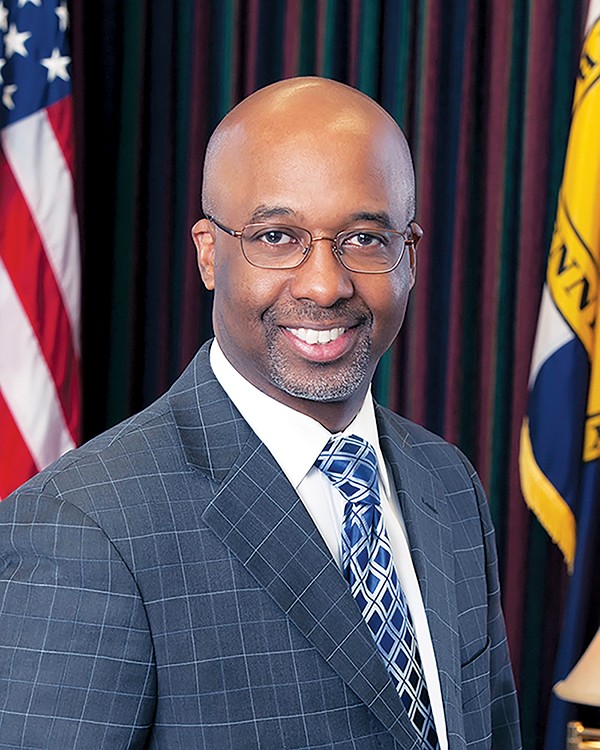

Council chairman Berlin Boyd then said, “for clarity purposes, let me read the substitute ordinance into the record.” Finally, clarity. Nope. Boyd simply read the same old blanket ordinance heading, the one about “the immediate removal of” statues from city-owned property.

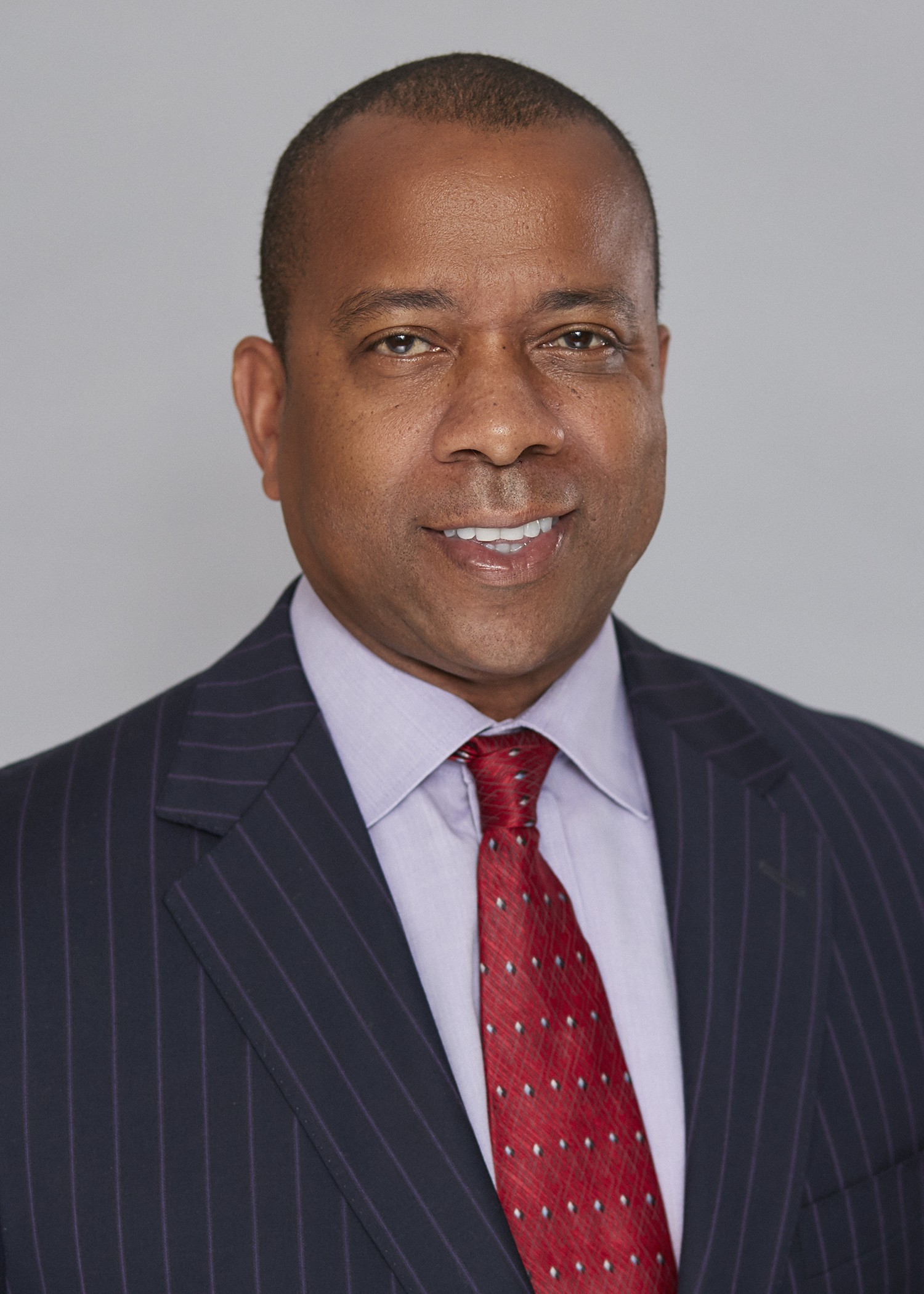

Council chairman Berlin Boyd then said, “for clarity purposes, let me read the substitute ordinance into the record.”

During the crucial vote no council member said the word “statue.” No one said “parks.” Certainly no one said “Greenspace Inc.,” a nonprofit that no one but those in the inner circle had ever heard of. No one said anything at all, really. The council moved on to other business.

But as we now know, that vote sent players in motion all over the city. That vote cemented an agreement Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland had already signed with Greenspace. That vote sent dozens of police and other public safety officials to cordon off the parks, a seamless orchestration that must have taken months to plan. The police moved in to protect crane operators hired by Greenspace to remove statues of Nathan Bedford Forrest, Jefferson Davis, and James Harvey Mathes.

The Flyer‘s editorial stance on the removal of the Confederate statues was clear for months. The paper favored their removal, the sooner the better. But concerns remain about the process — a legislative maneuver that shielded the public from a critical government decision, a maneuver that seemingly allows city government to pass legislation without public review or comment.

Ford said in an interview months after the vote, that the play was used to ensure public safety. He said other votes, such as one regarding residency requirements for city employees, have gone down the same way. The statues vote was scrutinized, he said, because of the public intrigue.

“There’s nothing that we have tried to do in the dark that we wouldn’t do in the light, as far as legislation is concerned,” Ford said, noting that if anyone had questions they could have asked him. “I don’t want people to think that this is something that is sort of a witch hunt or something, done behind the scenes.”

The Atlantic‘s U.S. politics and global news reporter David Graham, called the council play a “novel trick,” a “surprise move,” and a “novel strategy.” But he worried about the precedent.

“The distance between righteous civil disobedience and risky breakdown of rule of law is not as wide as it might seem, however, and it’s easy to imagine ways in which such a procedure could be abused,” Graham wrote. “What if local authorities defied state or federal authorities to erect a pro-Confederate statue?”

Graham also warned the trick play could bring legal challenges. He was right. The Sons of Confederate Veterans sued the city, a case still in mediation. Also, state leaders — Lieutenant Governor Randy McNally and Speaker of the House Beth Harwell — called for a review of the city’s entire statue episode from the State Comptroller’s Office of Open Records Counsel.

That report cleared the council, saying it “provided sufficient notice of its meetings and agendas to allow interested citizens the opportunity to attend.”

The council met the Tennessee Open Records Act, the report said, because it posted its meeting dates on its website, along with agendas, documents, and more. Though, it should be noted here, again, that the final statues ordinance was never posted online before the final vote meeting and wasn’t in agenda packets the day of the vote.

Tami Sawyer, who led the #TakeEmDown901 movement, said she was told the morning of the vote “what was supposed to happen.”

“When the ordinance wasn’t read, all I could think was … get to the park,” Sawyer said. “I was more focused on, ‘Was it going happen for real’ than anything else.”

Council member Morgan said the vote was “done in public” and that “you can’t do a complete substitute ordinance that wouldn’t fit into the subject of the heading.” That is, the ordinance you approve has to, at least, in some way, relate to the one it’s replacing.

In this case, doing something “relative to the removal” of the statues was close enough to “the sale and/or conveyance, at reduced or no cost, of such portions of the city’s easement in” Memphis Park, Health Sciences Park, and the Forrest Monument to Greenspace.

Morgan said the media was mad at the council’s handling of the vote “because they missed the story,” adding, “the reason you don’t announce that the statues are coming down … is because of the violence that we’ve seen,” citing protests and counter protests. It was done legally, he said, and pointed to the comptroller’s report as proof.

“So, I don’t regret how it was done,” Morgan said. “I do regret a lot of the discussion that happened beforehand and after. The protests have suffered from a lack of leadership and a lack of direction, but I can only control and participate in things that are inside [the council’s purview].

“We did it legally and safely so there’s not much more to say, and I certainly won’t apologize for it.”

Council member Patrice Robinson said she was “almost positive” that the council shared documents about the sale to Greenspace with the public. But she deferred to city council attorney Wade “because he was guiding us in the process of making sure that we handled everything in a proper and legal manner.”

Council member Patrice Robinson said she was “almost positive” that the council shared documents about the sale to Greenspace with the public.

When told the information was not shared, Robinson said, “I can only think we maybe need to look at our rules and how we handle that because it’s not just that particular situation. That’s the way it’s been handled in the whole two years I have been on the city council.”

Before responding to questions, Wade noted in a letter that this reporter “likes” the Facebook pages of the Sons of Confederate Veterans and Confederate 901. Wade said those likes “revealed an affinity for the views” of the groups and that “we will assume that your apparent bias will color your opinions” in this story, the purpose of which, he alleged, is “to denigrate the removal of the statues.”

[Note: I “like” those pages in the same way I “like” and follow a variety of groups that make news in Memphis. For example, I “like” the Memphis Zoo and Citizens to Protect Overton Park. — Toby Sells]

Wade noted that while the Tennessee Open Meetings Act requires some meetings to be public, “it does not guarantee all citizens the right to participate in the meetings.” The city charter, he said, allows the council to “amend any ordinance ‘at any time’ before final passage” and does it routinely. For evidence, he pointed to the annual budget ordinance, which the council “routinely amends” from the floor before a final vote.

As for directing the council through the statues vote, Wade said, “I do not direct anyone to do anything. I give advice, which the client is free to accept or reject.”

Council member Martavius Jones pointed also to the vote on residency requirements as an example of the council using the substitute-ordinance play. It’s legal, he said. But he was then asked if the method is good for open government.

Council member Martavius Jones pointed also to the vote on residency requirements as an example of the council using the substitute-ordinance play. It’s legal, he said.

“One of the things that I did after [the statues vote] meeting was to go back and make copies [of the substitute ordinance] to give to the media after we voted on it,” Jones said. “Because I believe in transparency in the way we operate as a Memphis City Council.”

It all seemed above-board to Deborah Fisher, executive director of the Tennessee Coalition for Open Government (TCOG). Notice was given. The purpose of the ordinance was clear, even if the details weren’t. Past that, it’d be up to a judge to decide if the council broke the law, she said, noting that her group has no open opinion on the statues issue.

“If nobody but the members of the governing body knew what they were voting on, it’s completely understandable why the members of the public would be upset about that,” Fisher said. “It’s really not how a governing body should work.”

Lobbying Against the Public

Hardly an eyebrow was raised last year when council chairman Berlin Boyd asked for money in the city budget to hire a lobbyist. They wanted to help set the city’s legislative agenda in Nashville.

But a fury erupted when the public found out what that agenda included.

On December 5, 2017, all but three council members voted to send the idea of instant run-off voting (IRV) back to Memphians on a referendum. Trouble was, Memphians had already approved IRV by 71 percent in a referendum back in 2008, and it was scheduled to be first utilized in the 2018 elections.

In a co-written guest column in The Commercial Appeal, former Shelby County Commissioner Steve Mulroy and former city council chairman Myron Lowery — both IRV proponents — said “the county election commission dragged its feet on implementation, inaccurately claiming that the county’s voting equipment couldn’t handle it.”

While some were scratching their heads about the council’s move to bring it back to a vote in December, the council had been hard at work on the issue — behind closed doors — since November. That’s when the council hired the well-known, Nashville-based Ingram Group to find a sponsor to introduce an ordinance to prohibit IRV. According to a Ryan Poe story in the CA last month, the council had been working “quietly” and “behind the scenes” to find a Senate sponsor for the bill.

While Wade told Poe the bill was moving “full steam ahead” in Nashville, the news of the council’s maneuver wasn’t playing well back home.

Theryn C. Bond excoriated the council at the podium back in December, reading from the council rules of procedure on a ranked-choice system by which the council itself uses to fill vacancies on the council.

“Now, what does that sound like to you?” Bond asked. “Sounds to me a lot like IRV. And what is good for the goose, should be good for the gander.”

Lemichael Wilson said of the council’s work to use taxpayer money to fight against something the public had approved, “to call this hypocritical would be a compliment.” Wilson said last autumn’s calls by council members to “give the choice back to the people,” now rang “hollow upon our ears.”

“Many believe this council — if nothing else — didn’t want Nashville telling it what to do,” Wilson said. “They believed it with such fervor that they supported the council in this late-night sale and removal of Confederate statuary.

“How we can now believe this council is ardently striving against legislative preemption when it is funding that very practice behind the citizens’ backs?”

Surprise!

The council’s committee agenda is usually posted on Thursday around noon. With a regularity that borders on routine, a new agenda is posted on following days with new items added in different committees.

What’s the issue? Well, for one, it goes against the council’s own rules.

“All proposed ordinances, resolutions, motions, and other matters submitted by council members shall be submitted in writing to the Council Office by 10 a.m. Thursday,” reads a section from the council’s rules of procedure.

Any council member can bring a new ordinance or resolution after that, but only if they present it in writing. Even then, “only items involving extreme emergencies may be added to the agenda,” after the Thursday deadline, according to council rules.

Those rules are often stretched or ignored.

In March 2016, council member Reid Hedgepeth filed a last-minute resolution on a Tuesday morning — as council committee meetings were already underway — that proposed giving the majority of Overton Park’s Greensward to the Memphis Zoo.

Hedgepeth’s surprise resolution said the zoo “has the greatest usage by citizens and visitors of any of the other various activities in the park.” It would have allowed the zoo to use the green space as a parking lot, add permanent buildings to it, or, really, do whatever they wanted with it.

The resolution was brought by Hedgepeth but its sponsors included Robinson, Bill Morrison, Phillip Spinosa, Jones, Janis Fullilove, Ford, Boyd, and Joe Brown. So, it seems there had been plenty of discussion about the resolution, though none of it was public. And it caught park advocates completely off guard.

“This outrageous and undemocratic power grab is a massive insult to the thousands of citizens who’ve participated in the ongoing public planning process, to the Overton Park Conservancy, which is engaged in mediation and litigation with the zoo, and to Mayor Jim Strickland,” read a Facebook post at the time from Citizens to Protect Overton Park.

Had the resolution been posted on Thursday, per council rules, it would have given proponents and opponents plenty of time to show up at city hall and express their views. Hedgepeth’s last-minute ploy only gave interested citizens about four hours to change their daily schedules; many showed up at city hall anyway.

The Commercial Appeal once sued the city over this very issue. The 1974 Supreme Court opinion put the law on the city’s side when it came to adding agenda items at the last minute. “Adequate public notice,” to the court was based on “the totality of the circumstances as would fairly inform the public.”

But a 2012 opinion from the Open Records Counsel to the Tennessee Municipal Technical Assistance Service (MTAS) said the office would not recommend last-minute agenda changes.

“From a best practice perspective, this office would not suggest that a governing body amend an agenda during a regularly scheduled meeting to include an issue in which the governing body knows that there is significant public interest,” read the opinion from Elisha D. Hodge, “and (the governing body) knows that if the item had been on the agenda that was originally published for the meeting, there would have been increased public interest and attendance at the meeting.” All of these issues — silent votes on important ordinances, behind-the-scenes lobbying in Nashville, and last-minute agenda items — are business as usual at city hall. Some of it has been going on for a long time. Legal experts may say (and have said) it’s all above board. But for Memphians, we ask, “Is it justice?” Let’s let Theryn Bond have the final word:

“The last time I checked, you guys work for us,” Bond said to council members last month. “So, come up from behind those closed doors, and roll up those sleeves, and dig into your districts. Because, trust me, it is nothing to get 25 signatures. Do I make myself clear?”

City of Memphis/Facebook

City of Memphis/Facebook  CDC

CDC

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker