“I wasn’t making a damn thing,” according to James Robinson. Robinson was remembering the year (1968) and remembering his 15 years working for the Memphis Department of Public Works. He was earning $1.65 an hour. He was a member of the almost entirely black labor force in Memphis known as “garbage men.”

As such, Robinson was an unclassified day laborer. He could be fired, by his (white) supervisor, on a moment’s notice. He had no regular breaks. He had no place to go to the bathroom or wash up. And he had 15 minutes for lunch. If it rained, he lost wages. If the day ran into night, he didn’t make overtime.

It was a low-paying job, and in 1968, it was a very dirty job. Memphians didn’t leave their trash in specially designed, wheeled containers on the curb. Sanitation workers had to carry garbage, often in unlidded, 50-gallon drums, off a property and lift it onto a waiting truck. And the garbage didn’t stop there. Workers had to clean an entire property, and that included fallen tree limbs, loose paper, grass clippings, and sometimes dead animals.

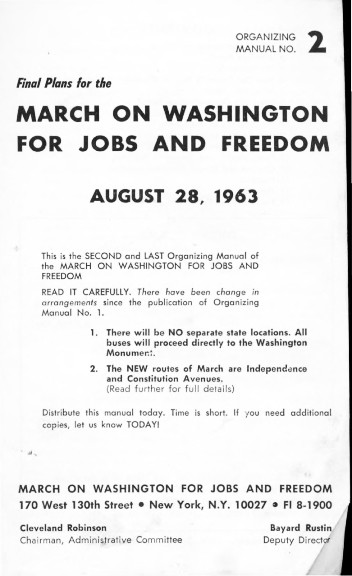

On February 1, 1968, one of those garbage trucks also carried two dead sanitation workers: Echol Cole and Robert Walker. They’d climbed into the barrel of the truck to escape a heavy downpour, but a possible mechanical failure sent the truck’s hydraulic ram into action. The two men were crushed, and on February 12th, nearly 1,300 black laborers in the Memphis Department of Public Works, without notice, went on strike. What they wanted was a union, but, as Michael K. Honey writes in his exhaustive, absorbing, definitive history, Going Down Jericho Road: The Memphis Strike, Martin Luther King’s Last Campaign, “[l]ittle did they imagine that their decision would challenge generations of white supremacy in Memphis and have staggering consequences for the nation.”

Honey, professor of African-American and labor studies at the University of Washington-Tacoma, has spent 10 years researching this story after penning two studies in the 1990s that focused on black workers, unionism, and civil rights in the 20th-century South. He lived in Memphis for six years as a worker for the civil rights movement, beginning in 1970. And he’s researched the city’s modern history as well as anybody: its polarizing racial attitudes, its unyielding government officials, its law enforcers, its activists, its labor organizers, its religious leaders, and the national leader who was shot dead here on April 4, 1968: Martin Luther King Jr. “A crucifixion event” is how Rev. James Lawson, a leading civil rights figure in Memphis in the ’60s, described King’s assassination, 39 years ago. King — his career at a crossroads — was himself 39.

“It’s almost a universal,” Honey said recently by phone from Tacoma. “Most people know that King was killed in Memphis, but almost nobody knows what the sanitation workers’ strike was about or that there was even a strike. People don’t know that King died in the middle of a struggle for the right to belong to a union.

“I see my book as presenting a somewhat different King — someone rooted in the labor movement as much as the civil rights movement. King had a profound appreciation of the issues relating to black workers. From the Montgomery bus boycott on, he was circulating among union people from all over the country.”

One of the many virtues of Going Down Jericho Road is its demonstration of King’s expanding concerns by the mid-’60s: economic injustice in America (and his troubled Poor People’s Campaign); workers’ rights (across all racial lines); the rising Black Power movement (in the face of King’s unwavering commitment to nonviolence); and opposition to the Vietnam war (in the face of opposition from both blacks and whites).

But what of Memphis and of King in 2007?

“The legacy of the ’68 movement has been very much incorporated into the city’s story,” Honey conceded, and he pointed to the strides the city has made in race relations. But it troubles him to return to Memphis. (And he returns often to visit good friends.) He referred to closed factories, the disappearance of union jobs, the poverty he still sees in Midtown, in South Memphis, and in his old neighborhood from the ’70s, North Memphis.

“This was the problem King was trying to address, and it’s still being ignored. And not only in Memphis. We have a U.S. president who’s willing to let the issue of poverty go. We saw that in New Orleans.

“But on the eve of the U.S. invasion of Iraq, I took note that people began talking about King’s speech against the Vietnam war — the one he made on April 4, 1967. In that speech, King explained why the U.S. keeps getting involved in these conflicts … how the U.S. has its priorities upside down: spending money on militarism when it should be spending money on solving the social problems that give rise to violence. I thought, back in 2003, that people are now turning to King to understand the mess we’re in.

“Conventional minds, however, want to typecast King as only a civil rights leader. It allows them to not talk about his broader spiritual framework and the larger issues he spoke about. I think people are beginning to move into a real understanding of King — King the moral leader. This is not about black and white only. It’s about human rights and economic justice, war and peace.”