Matthew Harris is the newest edition to the Contemporary Media team. He is a 2020 graduate of Rhodes College who interned with the Memphis Flyer and Memphis magazine before being hired as an editorial assistant. I persuaded him to watch all three hours and 20 minutes of Spike Lee’s epic 1992 biopic Malcolm X. Our epic conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Chris McCoy: So tell me, what do you know about Malcolm X?

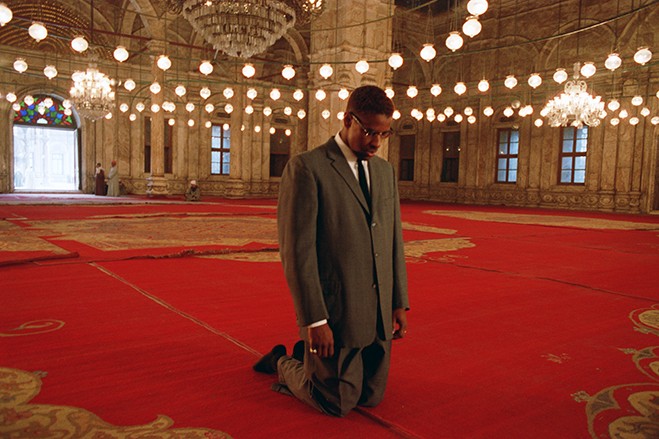

Denzel Washington as Malcolm X

Matthew Harris: I know what I have learned in the American school system. I know he was a civil rights leader. At first, he was anti- working with the African-American establishment. But then that changed close to his death, and he was really like, “You know we really need to stand together with the African-American civil rights movement. We need to be one unified voice.” But he died. A lot of what I know comes secondhand, from hearing my grandparents talk about it, my mom talk about it. But you know, I went to high school in Texas, and we didn’t talk about Malcolm X or any other outside-the-mainstream leaders. Ironically enough, I watched I Am Not Your Negro, which is a documentary based on the works of James Baldwin, two weeks ago. That was really the first time in my life where I was like, “Oh, wow. Okay. This was the movement. There were all these civil rights leaders like Fred Johnson I never really learned about in school.”

Chris: Well, you’re about to learn a lot more. What do you know about the movie Malcolm X?

Matthew: I know It’s a Spike Lee film, and it stars Denzel Washington.

Chris: Have you seen other Spike Lee films?

Matthew: I’ve seen Do the Right Thing, BlacKkKlansman. I ended up watching Da 5 Bloods very, very late last night. Chi-Raq was also by him. I’m a huge Spike Lee fan. I was talking to my mom and told her I was watching Malcolm X because I was helping a friend for something at work. She said, “Oh yeah, you’re going to be mad at the end. You’re going to be mad because Denzel didn’t win an Oscar for his performance, and he was amazing.”

Chris: Not to bias the experiment, but I think your Mom has a point.

201 minutes later …

Chris: Okay, Matthew Harris. You are now someone who has seen Malcolm X. What did you think?

Matthew: Oh, it was really, really, really good. The first half was very hard to watch. There were a lot of decisions that were made where I found myself saying, “No! No! Don’t do that! Just walk away!” The conversation he has with his wife Betty, where she says, “Open your eyes!” is now in my top five movie moments. That’s such a hard scene. He really owes his life to the movement, and is ready to do anything for them. But they were taking advantage of him. You can just tell, knowing this is based on his book, you know it was hard for him to do, and it was such a hard conversation to play. But they just knocked it out of the park. It was so well done.

Chris: Are you upset, like your mom said, that Denzel didn’t get the Best Actor Oscar?

Matthew: I’m pretty angry. Angela Bassett was amazing as well.

Chris: Oh yes. She’s always amazing.

(left) Angela Bassett as Betty Shabazz

Chris: Do you know who actually won, instead of Denzel?

Matthew: Who?

Chris: Al Pacino for Scent of a Woman.

Matthew: Huh.

Chris: I know. That was one of those awards that was a “He’s done so much good stuff, we need to give him one” kind of thing. But come on! Denzel’s so good. The way he carries himself from phase to phase in this movie, you can sort of watch the moral maturity of his character evolve, just from the way Denzel holds his shoulders. It’s stunning.

Robbed

Chris: So what do you think about watching this today? What does this movie say to 2020 America?

Matthew: There were a lot of messages and shots that were so very poignant, especially in the latter half. There’s one shot of Malcolm near the end that I want to say is a fisheye effect, or something like that. And then there’s a lady on the street who stops him, and says, “Don’t let them get you down, don’t let them talk to you like that.” And that’s something Spike Lee does. It’s in BlacKkKlansman as well, with a burning cross. The message of that … As a Black man, there have been times when there’s so much pressure and social tension going on. There’s a weight there. You find yourself with these moments where you’re just on autopilot. I remember there would be days at Rhodes where something would happen, and I would just walk past my friends. They would be like, ‘Hey, Matt, how are you doing?” And I’m just not there, because I’m not in a moment. Keep moving, keep moving on. You have to put yourself into that mindset. That’s how you get from day one to day two because you don’t know any other way. You hear the slight against you, or you see systemic racism, and you’re like, I just can’t deal with that today. You really zone out. I loved that scene.

Chris: That’s one of Spike’s signature shots. It might not have been the first one, but it’s the best one, because of Denzel’s face. What’s going on is pretty simple. It’s a dolly shot with the camera angle pointing up. The actor is just riding on the dolly with the camera. He’s in motion, but he’s not walking. It looks like he’s gliding. He’s ascending, because the motion of the trees in the background is downward, so it’s like he’s ascending to heaven. It’s kind of a Jesus moment. He’s in the Garden of Gethsemane, awaiting his betrayal. Not to be insensitive to him as a Muslim. I think Spike kind of calls himself out there. The woman you were talking about who stops him on the street says “Jesus will protect you.” I was like, yeah, probably not the best thing to say to this guy at this moment. But she meant well.

Never Seen It: Watching Malcolm X with Flyer Writer Matthew Harris (6)

Chris: This movie came out when I was in college. I was already a big Spike Lee fan, because I was a film nerd and I loved She’s Gotta Have It and Do the Right Thing. This is Spike doing the prestige studio movie, 1992 style. It’s a formal exercise for Spike, where in Do the Right Thing, he’s free form. He’s just doing his own thing. But this is a big studio thing, and he did it so much better than anybody else at the time. He’s just good at everything. I’m so jealous of him. He’s great with actors. You just watched Da 5 Bloods, right? What did you think of that?

Matthew: It was good. I think you can sort of categorize Spike Lee films in two ways. There’s the overtly politicized movies, like Malcolm X and BlacKkKlansman. Then there’s the sort of more internalized African-American movies, like Do the Right Thing.

In Da 5 Bloods, the entire premise of the movie is bringing back money to the community that they feel is rightly theirs. But part of it is also dealing with how African Americans see themselves. How do they deal with their struggle, their problems? BlacKkKlansman and Malcolm X, you have characters who live in a political sphere. It’s about how they navigate the space around them, how they exist in the space around them. So, one thing I harken back to in BlacKkKlansman, you have this really strong African-American lead who has to go through changes. But then at the end of the day, he realizes it doesn’t matter what changes he goes through. He’s just found a way to live, but the world doesn’t really care.

In Malcolm X, we have a character who goes through significant changes. We follow him throughout his entire life, and in the end, nothing changes. He’s murdered, Black men and women are still facing prejudice, the injustice is still occurring, and the movie ends. That’s one thing I’ve always liked about Spike Lee movies, especially the politicized ones — they don’t have happy endings. That’s real life. Even Da 5 Bloods is not a super happy ending.

Chris: Most of them die. And Delroy Lindo dies sort of unredeemed. Did you notice him in this movie? He’s so good as Malcolm’s criminal mentor.

(left) Delroy Lindo as West African Archie, Malcolm Little’s criminal mentor.

Chris: I was keeping track of the timing. The first hour is basically a gangster movie.

Matthew: It’s like a gangster movie, then it’s like The Green Mile or Shawshank Redemption, then it becomes a political movie.

Chris: And when it’s The Shawshank Redemption, it’s better than the actual Shawshank Redemption! Spike’s like, ‘Oh yeah, I can do this!” Another one he does is JFK, the Oliver Stone movie that was out the year before this. I really noticed it during the part where Malcolm made the comments about the assassination. It’s cut like an Oliver Stone montage in that moment. Spike is just casually doing everyone else’s riffs better than they could.

Like you said, it’s kind of a hard movie to watch, because it’s almost three and a half hours long. But it doesn’t feel like I’m wasting my time. I’m the biggest nerd you’ll ever meet, but when I spent three hours with those Hobbit movies, I felt like I was wasting my time.

Matthew: There’s no space wasted in this movie.

Never Seen It: Watching Malcolm X with Flyer Writer Matthew Harris (3)

Chris: One thing that struck me this time was, this isn’t just a movie about racism. It’s exploring racism as a phenomenon. It poses the question, which Malcolm’s life does — when he was a Black separatist in a cult of personality, as the Nation of Islam was — was he a racist? Ultimately, he comes around to cosmopolitanism after he goes to Mecca and sees everybody worshiping together. He gets a new perspective when he leaves the racist environment of America. I don’t have the answer to that question, and that makes it uncomfortable to watch for a lot of people.

Matthew: Being a younger African American, and going to college at a PWI, a Primarily White Institution, I met people on different ends of the spectrum. In Texas, I grew up as pretty much always the only Black person in the room. People are always going to ask me questions. People are going to do microaggressions towards me. But they don’t know. I have very curly hair, and some of my earliest memories from middle school are people playing with my hair. … They had never been around people with Black hair.

So, when I came to Rhodes, I was very different than people there, because I was like, “Hey, you know it’s okay to tell people that they’re wrong and to educate people.”And I met a lot of people who were like, “No, they should know, and they’re either with us, or they’re against us.” I saw so much of that in Malcolm X, with the kind of transformation he makes. At Boston College, there’s this one white lady who asks, “What can I do to help you?” And he says, “Nothing.” To this day, I know people who are like that. “There are no good white people. They’re all out to get us.” I’ve seen people, as they get older, make the transformation that Malcolm makes. I think a lot of African Americans make that change in their life. They’re like, “Is my outlook toward other people, toward people who are trying to be allies, problematic?”

‘Nothing.’

And it’s so crazy because I had a conversation with my mom last week. We were talking about Juneteenth. We’re from Texas, and Juneteenth is a state holiday. We got the day off. My mom never celebrated. She thought it was really dumb. And with everything that was happening, people were wishing her a happy Juneteenth. And she’s like, “Am I a jerk or an asshole if I email people back and tell them I don’t celebrate Juneteenth?” We had a really long conversation where I told her I think that she’s being a little hard. Because these are people who don’t know any way to ally. This is the way that some people told them that they can be an ally. They’re doing their best, they’re making an effort, and you’re basically just shitting on them for making an attempt.

Chris: I think that the tribal instinct, you know, the instinct toward being a member of a group of people who are like you, a sort of extended family group, is natural. And it served humanity well for a really long time. But it also turns toxic. We just have to figure out a way to extend that feeling in people toward all of humanity at once, if that makes any sense. I don’t know if I’m making sense right now. That’s the way forward. And what Malcolm says in the letter that he writes to Betty from Mecca is that racism is leading toward an inevitable disaster. That’s someone who has seen a higher wisdom.

Matthew: That reminded me of Kendrick Lamar at the end of To Pimp a Butterfly. In the song “Mortal Man,” he has a conversation with a recording of Tupac. One of the things he talks about is that there’s going to come a point in time when African Americans are going to start shooting back. He likens it to Nat Turner. That’s something I’ve always thought about, with things going on today. You can only push and push and push so much before people push back. I’m not going to compare 1960s America with 2020 America, but I think a lot of the pushback we’ve seen recently is due to 400 years of systematic oppression, of taking people’s voices away. Of saying, no, you can’t protest like that. You can’t say this, you can’t kneel. You eventually back people into a corner, where they say, “How can I speak out on the injustices that are in front of me without breaking the law?” If the only way you’re going to listen to me is by breaking the law, and that’s the only way change is going to happen, what other choices do you have? I care about my family, and I care about the people around me, and I care about the people who look like me. Every time I’ve tried to raise my voice, you’ve shut me down, but when I go out and shut down a street, that’s illegal. So when I first saw that, that’s all I could think of. All that anger and frustration, and people are going to rise up. And people are rising up.

Never Seen It: Watching Malcolm X with Flyer Writer Matthew Harris (2)

Malcom X is streaming on Netflix.