As the song made famous by the late Doris Day has it, “Que sera, sera/Whatever will be, will be/ the future’s not ours to see/Que sera, sera … ”

Indeed, but the residents of Memphis and Shelby County, like those elsewhere in the inhabited world, can’t be blamed for wondering: Just what does come next?

So far, there have been no armed protests locally, like those that took place in the Michigan state capitol last week. And no reason to, inasmuch as the officialdom of Memphis, Shelby County, and the county’s other six municipalities have all concurred on a business-reopening plan to begin this week.

But there remains a distinct possibility that medical circumstances could impose a hitch on those plans. After all, it is known that the reopening plan was originally scheduled to be announced by the powers-that-be on Monday of last week but was delayed until Wednesday by a reported spike in the number of coronavirus cases.

Still, here we are, with a timetable for reopening, after tiresome weeks of isolation and social distancing and shuttered establishments of virtually all kinds, public and private. Local officials made every effort to accentuate the positive, but there was inevitably a tight-lipped ring to their statements, a left-handedness to their public optimism. The opening paragraph of the reopening announcement, undersigned by mayors and health officials, for example, went this way:

“After careful study of the data, and on the advice of our medical experts including the Shelby County Health Department, the mayors of Memphis, Shelby County, and the six surrounding municipalities have determined that May 4, 2020, is the date that we can begin phase one of our Back to Business framework.”

Brandon Dill

Brandon Dill

Mayor Jim Strickland

That first salvo of official broadsides had Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland proclaiming this: “Along with our doctors, we believe it’s time to slowly start opening our economy back up and get Memphians working again.”

Not exactly bursting with confidence. And Strickland sounded even less certain when asked to elaborate in interviews. Here he was, speaking to WMC-TV, Action News 5 last Thursday: “We feel comfortable that over the last month, for the most part, the new cases and hospitalizations have remained fairly static.” [Italics ours.] With all due respect, the effect of those two qualifying phrases — “for the most part” and “fairly static” — is daunting.

The fact is, the way forward is strewn, not with palms or garlands, but with thorns and pitfalls. April was, if not the “cruelest month” of poetic legend, unkind enough. At the beginning of the month, some two weeks into his March 23rd stay-at-home order, Strickland took stock of the city’s financial outlook and found, as he put it, anything but a “pretty picture.” With the budget yet to be calculated, the mayor foresaw revenue losses of some $80 million in the coming fiscal year. As the month wore on, his estimate rose to at least $100 million — fully a seventh of what would be a maintenance budget of $700 million.

Strickland said sales taxes, which represent about 23 percent of the operating revenues for the city’s general fund, were estimated to decline by 25 percent, with a worsening of a situation that had already seen “significant reduction in the services we provide to thousands of citizens and layoffs of hundreds of city employees.”

In the course of the month, the city received assurances of $113 million from the federal government, but it could not be used as bailout money. The strings were that every penny would have to go for COVID-related expenses. Ditto with the $50 million of CARES Act money expected by Shelby County government. The city holds a reserve fund of some $78 million but needs to hold on to most of that as a last resource in case the disaster takes even more unpredictable turns.

Conflict in County Government

Shelby County’s budget situation is uncertain as well, and like much else in county government, is subject to a kind of internally raging civil conflict. The discords of the moment, under Mayor Lee Harris, are hardly as pronounced as were those of the administration of previous Mayor Mark Luttrell, who, during his second term (2014-2018) found himself almost totally estranged from the Shelby County Commission.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Mayor Lee Harris

Although Luttrell was a Republican and the commission had a Democratic majority, their differences were not partisan. Indeed, Luttrell faced his severest tests under two Republican chairs, Terry Roland and Heidi Shafer. Democrats still dominate the commission, but party loyalties, now as then, provide no cushion for Harris, himself a Democrat. His difficulties, like those of Luttrell, stem from disagreements over budgetary matters.

Luttrell’s alienation from his legislative body began when he evinced a determination to play fiduciary matters close to the vest, withholding information in 2015 about a looming budget surplus that commission members, once they tumbled onto its existence, decided they had plans of their own for. From that point to the end of Luttrell’s tenure, a power struggle persisted. When Harris took office in 2018, he took pains to express solidarity with the commission that had been elected that year, but discovered that maintaining an effective liaison with commissioners required a more systematic and continual effort than he had realized.

When he proposed his first budget in early 2019, he told commission members he wanted passage that very evening. He didn’t get it, of course. The budget didn’t get finalized until weeks later, after the usual give-and-take of negotiations. But in essence, he hazarded something similar this year, announcing last month, in the first blush of the coronavirus crisis, that he’d worked out a series of emergency reductions, across the board of county agencies, totaling $10 million, that would allow the county, by the nearest of near things, to escape bankruptcy.

Several department directors disputed his cuts, and the commission members couldn’t agree on them, and the bottom line was that nothing got done, not even a $2.5 million appropriation that was to have been the county’s contribution toward the costs of PPEs and other local COVID expenses.

Second thoughts on the commission’s part got that latter omission rectified two weeks later, and by then Harris had retooled his own plans, announcing a “lean and balanced” austerity budget of $1.4 billion that now required $13.6 million in cuts as well as a loan of $6 million from the county’s fund balance, leaving that reserve fund at the “go-no-lower” level of $85 million. There were a few fillips, too, in the way of pre-K expenditures, money for the sheriff’s deputies who’ll have to be hired to police newly de-annexed areas of Memphis, and a few million dollars extra for the schools.

The gremlin in the mix was the ever-unpopular idea of upping the county’s wheel tax, to the tune of an additional $16.50 to be added to the base automobile license fee of $50. No other place to go, said Harris, inasmuch as local property and sales taxes had already topped out.

Between that meeting and this Monday’s, the commission held committee meetings last Wednesday in which disagreement over budget possibilities flared into open name-calling between Commissioner Edmund Ford Jr. and Harris.

Serving as vice chair to budget chair Eddie Jones, the two of them opened up a tear in Harris’ plans, which Ford called “garbage,” floating a plan to ignore the mayor’s “lean”model budget and replace it with a thinly reconditioned version of the old 2020 budget, coming in at $1.3 billion.

“I used to think I was halfway decent at math, but it’s obvious that I can’t add,” CFO Mathilde Crosby said. Harris accused Ford of having been a “bloodletter” when they both served on the Memphis City Council, and Ford reciprocated that Harris was “presumptuous and arrogant and ignorant.”

Perhaps wisely, Harris kept his distance from Monday’s commission meeting, at which the Ford-Jones idea of rehabbing last year’s budget was happily forgotten and the mayor’s own “lean” budget was equally ignored. With all hopes of agreement dissolving, Commission Chair Mark Billingsley seized upon the expedient of a budget retreat to be held on Friday in FedEx quarters at Shelby Farms, with only the commissioners, the mayor, CAO Dwan Gillom, and CFO Crosby there to reason together at six-foot distances and find both the humane initiatives favored by Commissioner Tami Sawyer and the “shorter shoestring” demanded by conservative Republican Commissioner Brandon Morrison.

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

Matters of State

Governor Bill Lee’s own “shelter-in-place” resolve was hardly long-lasting, and it was none too stout to begin with, although an online survey of Tennesseans, conducted by a condominium of northeastern universities found that Lee’s now-you-see-them, now-you-don’t actions have been welcomed by some 64 percent of Tennesseans, while only 13 percent disapproved.

In Nashville, this year’s session of the General Assembly was abandoned when the dimensions of the pandemic and its reach into Tennessee became clear. It was at a time, for better or for worse, of much unfinished business. Left pending were such matters as the funding (and timing) of private-school vouchers, the designation of the Bible as the state book, a carry-over anti-abortion bill, and open-carry gun legislation.

As reported by Erik Schelzig, the diligent and ever-accurate editor of the Tennessee Journal newsletter, “Senate leadership has made it clear its preference is to focus only on downward adjustments to the budget required by the economic impact of the coronavirus. But a vocal faction in the House wants to instead throw open the doors to the legislation left hanging when lawmakers left town in March.”

A not unimportant matter is the question of whether state legislators, if indeed they resume deliberations by the planned date of June 1st, would authorize “no-excuse” absentee voting. Early voting for the August 6th election round is scheduled for July 17th, mere weeks later. As of now, a firm cut-off date of May 8th still applies to absentee applications. As Schelzig notes, “There’s been little sign so far state Republicans are becoming more receptive to liberalizing rules on voting by mail. And they have ample political cover from President Donald Trump, who has been a vocal critic of allowing more absentee voting. If it remains just Democrats advocating for sweeping changes to Tennessee’s current vote-by- mail laws, the issue will likely be dead on arrival.”

Locally the ballot will contain a mini-Shelby County general election and, as elsewhere in Tennessee, a primary for state and federal offices. The much-beleaguered county commission, on which Democrats have an 8-to-5 partisan edge, has formally resolved both to seek an extension of the absentee ballot and to urge the county’s Election Commission to purchase new equipment enabling hand-marked paper ballots. Indeed, the commission has conflated the two matters into a single resolution, which has passed twice now with the minimum seven votes required.

Under the more limited approach, a small number of committees would meet the last week of May before gaveling into session June 1st for as little as a week. Under the situation-normal approach, the session could last as long as three weeks — or even butt up against the end of the budget year on June 30th.

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

The Pending August 6th Election

Leaving aside the seemingly remote chance that a re-summoned legislature would facilitate an expansion of absentee voting, the chance that Governor Lee would support such an undertaking is equally unlikely. As indicated, the issue has no place in the playbook of the state’s Republican super-majority.

What is more to the point of reality is the issue of new voting machines for Shelby County, which county election administrator Linda Phillips has expressed hopes of putting to use in time for the forthcoming August election.

As indicated, early voting for that election is scheduled to begin on July 17th, a fact that presents a drastically foreshortened timetable for resolving a matter that has been seriously contested, in one way or another, for years, and confounded local elections for a decade or more.

No one needs to be reminded of the numerous electronic glitches that have led activists to join forces to campaign for a particular kind of machinery, which, perhaps ironically, constitutes a throwback to a less technological time. Among these activists are Shelby County Election Commissioner Bennie Smith, an acknowledged expert in the field of voting machinery; law professor and former Shelby County Commissioner Steve Mulroy; White Station High School government teacher Erika Sugarmon; and Mike Kernell and Carol Chumney, both former state representatives and veterans, respectively, of the Shelby County School Board and the Memphis City Council.

All of the foregoing are advocates of hand-marked paper ballots and argue that given Shelby County’s own checkered and error-prone voting history, and in acknowledgement also of the hacks and rumors of hacks that have plagued national elections, a resort to hand-marked ballots verified by scanning machines would be both safer and less costly. And, in a time of potential viral infections of metal surfaces, they would also be safer than the kind of ballot-marking devices that Phillips and the GOP members of the Election Commission have expressed a preference for.

So far the battle over voting devices has been a back-and-forth affair, and the forced reversion to electronic webinar meetings of the Election Commission occasioned by the coronavirus outbreak has complicated things further. A definitive choice of machine vendors by Phillips and a subsequent vote on her recommendation by the Election Commission members were both aborted by an electronic snag that kept member Brent Taylor, a Republican but a potential swing voter, from participating in a virtual executive session of the EC last week.

The Election Commission is slated to have another go this week, and so, for that matter, is the Shelby County Commission, which, unlike the EC, is dominated by Democrats and has repeatedly voted its preference — twice recently — for hand-marked ballots. Given the fact that the county commission controls the purse strings, the stage is set for a possible showdown between the two bodies over the voting-machine matter.

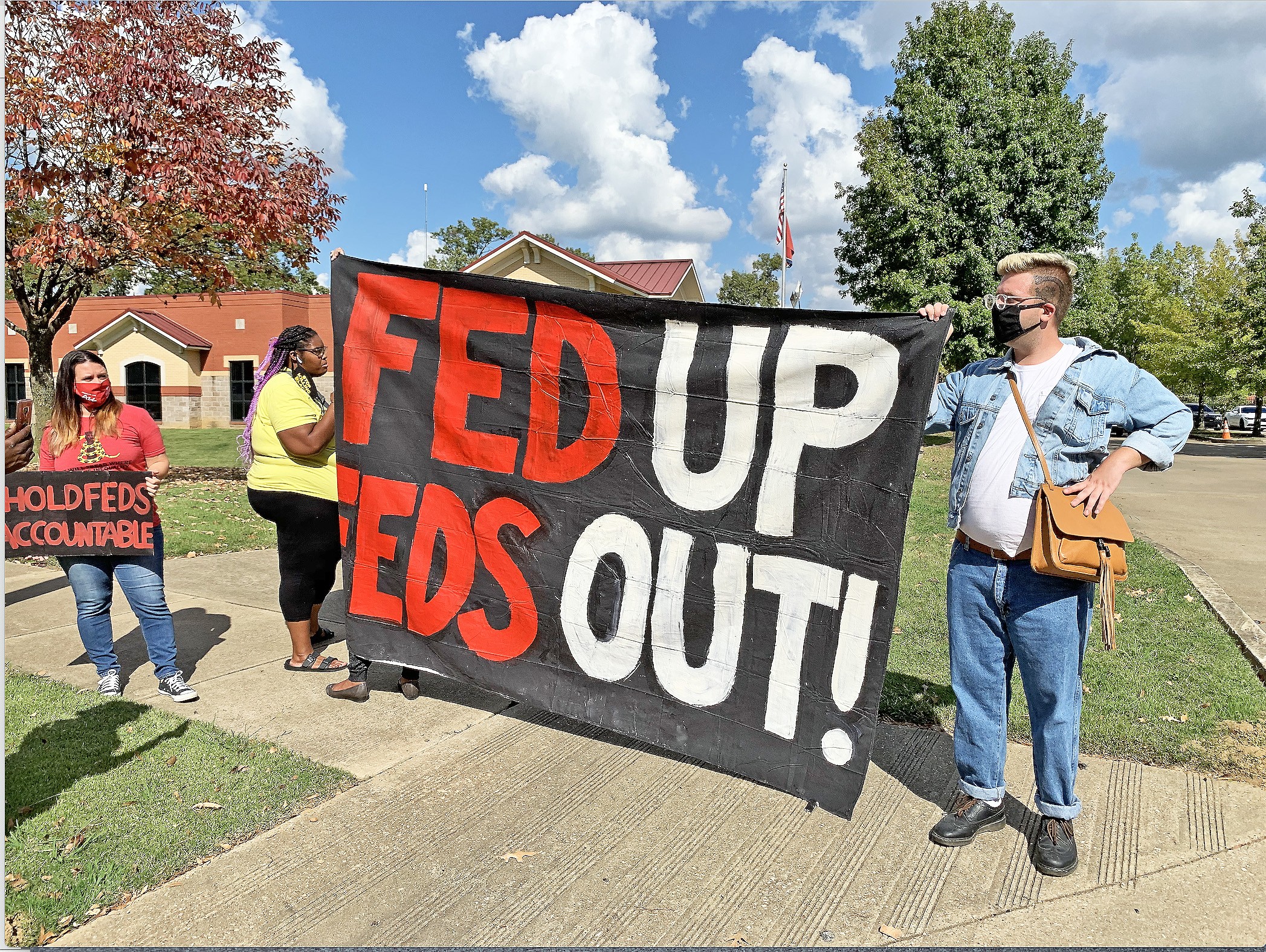

Meanwhile, the major pressure on all public bodies is the determination on so many people’s part and in so many jurisdictions everywhere to resume public activities — in advance of the reasonably arrived-at phases announced by President Trump requiring 14 straight days of declining coronavirus cases, advances in testing and contact tracing, and much else — parameters that have been roundly ignored everywhere — and not least in the White House itself.

In a recent discussion on CNN with Wolf Blitzer, various experts were heard to theorize that a second, more virulent phase of the pandemic would be coming in the fall and that, sans some unforeseen good fortune to concocting a vaccine, the plague would be with us for at least two more years.

That, said one of the authorities on tap, explained the sudden mania to hit the beaches, the supermarkets, and the national shrines. It was a matter of get-it-while-you-can, the scientist — not a fantasist — theorized. And it is undeniably a goad to our public bodies. Somewhere out there our future beckons — into some rosy and becalmed sunset in which to find our dreams or, if things should take a dystopian turn, there’s Edgar Allan Poe and “The Masque of the Red Death.”

And there is surely something in between.

Brandon Dill

Brandon Dill  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker  Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker