Apropos Memphis’ homicide wave: To put it bluntly, we are indeed up against it — the “we” including Mayor Jim Strickland, his interim Police Director Michael Rallings, the members of the Memphis City Council, and … who

else? Oh, yes, that “we” includes us, all the residents and businesses of Memphis and Shelby County, and all the tourists and other visitors who come here, drawn by the city’s legendary reputation for barbecue, boogie, and whatever else.

Specifically, count two of downtown Memphis’ foremost attractions, Beale Street and the Bass Pro Pyramid, within that group of potential victims of illegal violence — and, hey, summer, whether destined to be the long, hot version or not, hasn’t really even gotten started yet.

When Justin Welch, a distressed and/or mentally unstable 21-year-old, went on a shooting spree Saturday night, wounding innocent people in the Pinch District and Bass Pro and killing Police Officer Verdell Smith with a stolen vehicle, he put an exclamation mark on what was already an untenable situation.

Strickland must have known what he was getting into when he ran for the mayoralty, an office of responsibility that he’d had an opportunity to observe during his eight years as a city councilman. And we can only hope he knows what he’s doing now as he sets forth on what would seem to be a new course of active “partnerships” with other law-enforcement agencies: namely, the Tennessee Highway Patrol and the Shelby County Sheriff’s Department.

For obvious reasons, there has always been some jurisdictional cooperation between the Memphis Police Department and these and other agencies, including the Tennessee and Federal Bureau of Investigation. But this new arrangement is different; it puts a new spin on the old conundrum of whether the sum of separate parts can be greater than the whole.

We are reminded of another not-so-distant time, the late 1980s, when the “jump and grab” incursions into Memphis of the late activist Sheriff Jack Owens were regarded with a fair amount of jealousy and suspicion by the MPD and city government at large. The new combine of crime-fighting forces has, by the very fact of its being proposed, become a graphic illustration of the emergency we seem to have found ourselves in.

Simultaneous with an upsurge in homicides, surely the most chilling spectre on the public horizon, there are basic matters affecting the MPD that must be resolved. There needs to be a permanent police director, pronto. And, even though we have been assured by the wise lights in our local governments that the reductions in benefits for our police officers and other first responders were absolute fiscal necessities, we cannot regard this matter as closed. Strickland’s proposals for reactivating PST assistants and for increasing pay and other incentives may, in fact, not be enough to offset what is clearly an understaffed protective infrastructure.

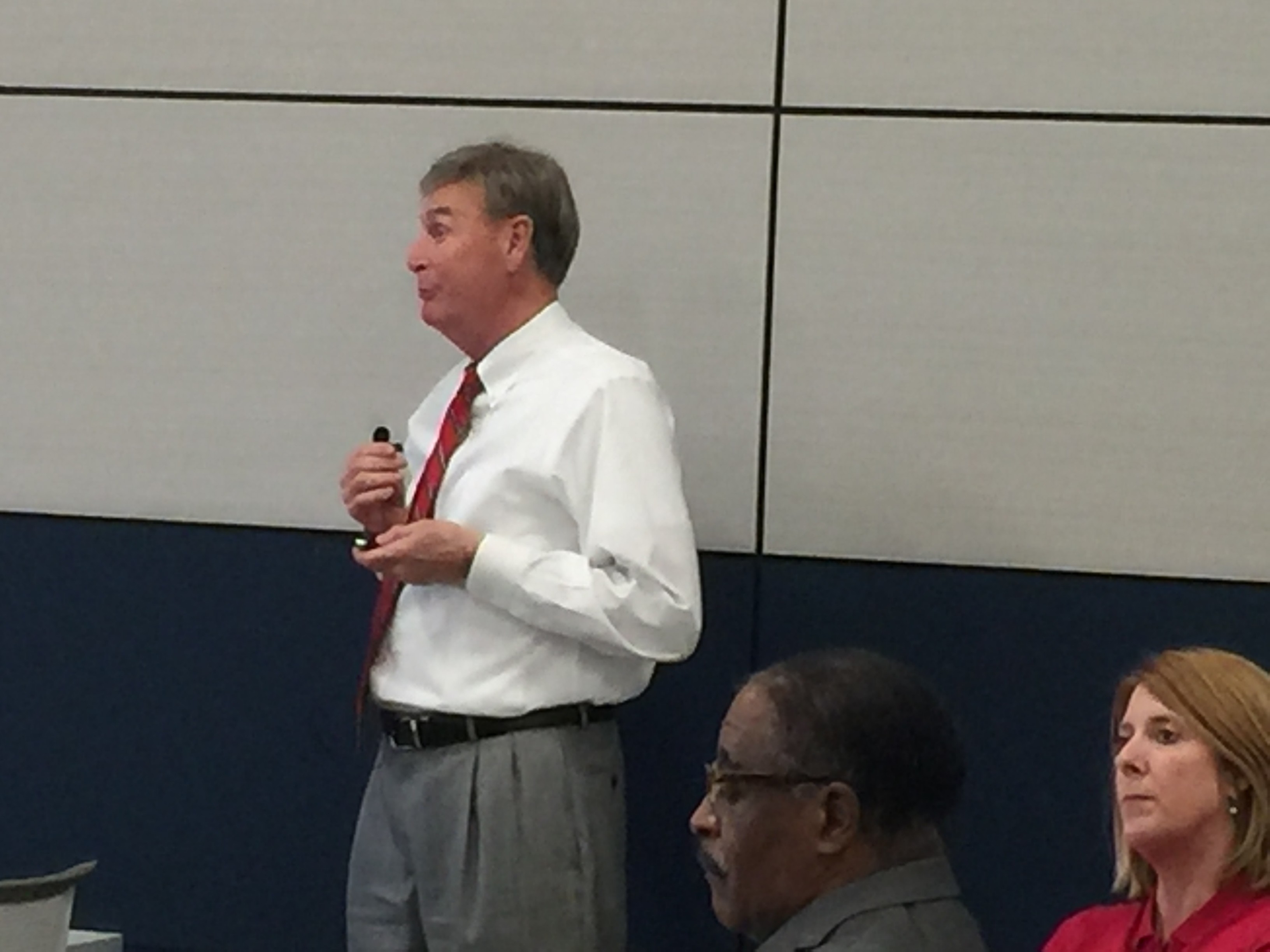

Meanwhile, Strickland is not the only public official who is on the spot; another is former district attorney and state Safety and Homeland Security Commissioner Bill Gibbons, who will shortly be assuming his new dual role of president of the Memphis Shelby Crime Commission and director of the new Public Safety Institute at the University of Memphis.

Let’s hope Strickland is on the right track with his new crime plan, but we need as many new answers as we can come by.

JB

JB  JB

JB  JB

JB  JB

JB  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Memphis Police Department

Memphis Police Department