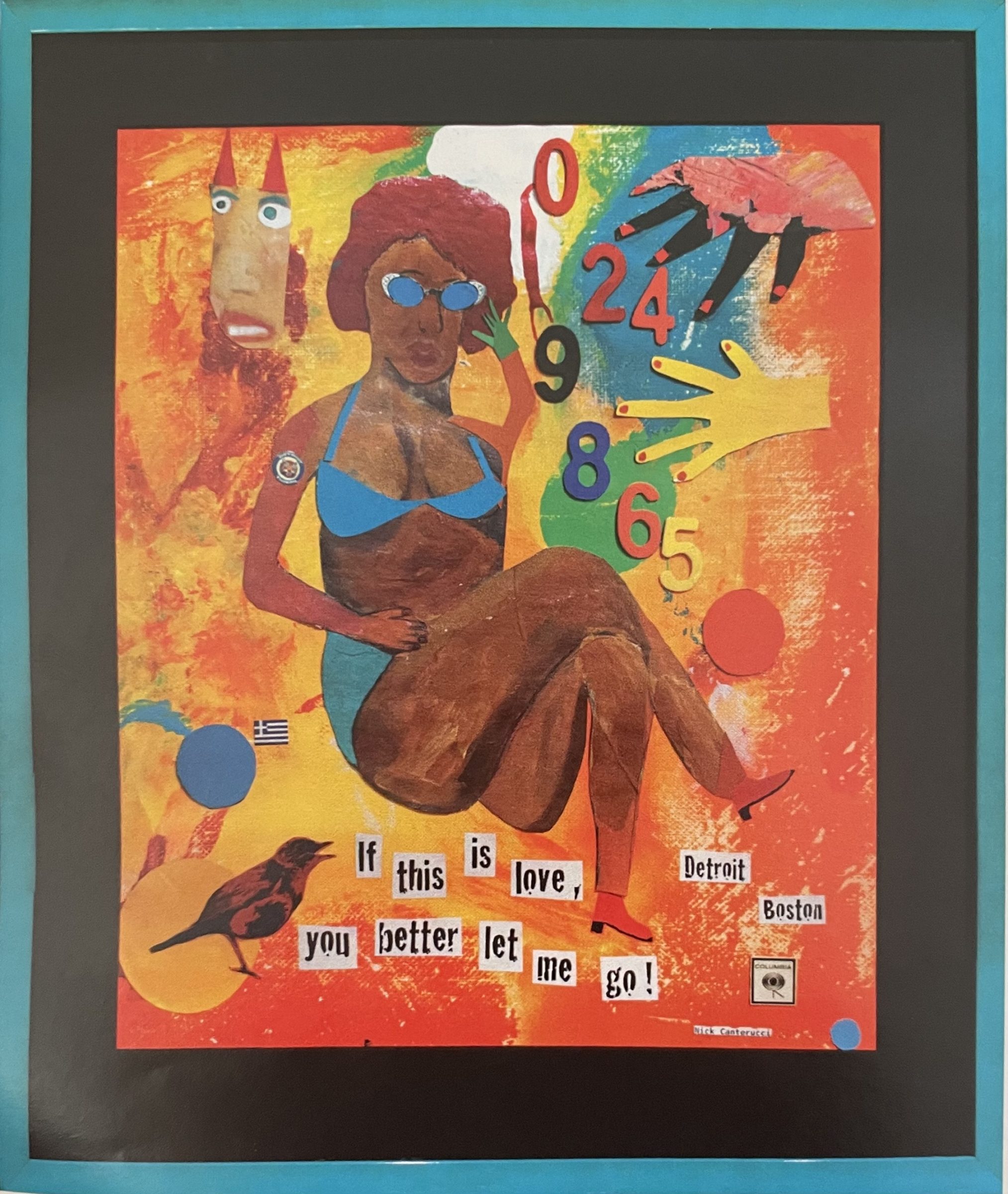

If you’re even the most casual reader of the Memphis Flyer, you’ve seen Jeanne Seagle’s work. Just turn to the weekly “News of the Weird” column every now and then, and you’ll see one of her quirky illustrations. But this week, if you head to the Medicine Factory, you’ll find the work she’s proudest of — her drawings and her watercolors of Dacus Lake, across the Mississippi River in Arkansas.

Seagle has been fascinated by this area for years now. After all, it’s where she started to get to know her husband Fletcher Golden, who lived at a fishing camp in the area at the time. “We would just wander all over that land while we were dating,” she says. “It was so much fun.”

Often, she returns there — to hike, to paint with watercolors, and to let her surroundings wash over her as she takes photographs to reference later in her drawings. She thrives in nature, she knows.

“I just love going over there. I love these scenes. I love these landscapes. That’s my spot,” Seagle said in an interview with Memphis Magazine last year.

Today when we speak about the Medicine Factory show, “Of This Moment,” which features new works, she notes how she hasn’t tired of the subject, especially with its ever-changing qualities. “In this show, I have a picture called Fallen Tree, and I have drawn that tree several times in other pictures when it was still standing,” she says. “That’s the thing about drawing landscapes, you can just focus on one spot and nature takes over and changes things constantly. … I find it endlessly fascinating.”

For three or four hours a day, she draws scenes of nature from photographs she’s taken at Dacus Lake, just a drive across the river from her Midtown studio. Sometimes, she’ll play blues CDs to fill the space with the rhythms of the Delta as she stills her focus on rendering the smallest of details — grooves in tree bark and wisps of grass — with careful marks in charcoal and pencil.

These black-and-white drawings take weeks to complete, sometimes up to two months. She’ll fold over the Xerox copies of photos she’s taken in some places, making entirely new compositions, adjusting the wilderness to her aesthetic liking. From these gritty images printed on copy paper, Seagle gleans details that an untrained eye would not recognize. She knows this art, inside and out, just like she knows these woods, harvesting their most innate qualities from her memories.

Unlike her illustrations that favor stylization, Seagle renders these images realistically, leaving no detail spared. The scenes are still, out of time. A sense of wonder remains in her drawings, inviting the viewer to slip into nature’s serenity, only a few miles from the grit and grind of Memphis.

After decades of working as an artist, Seagle has slipped into a serenity of her own, as if all her prior artistic endeavors have led to this moment. She’s experimented with styles and challenged herself many times over, she says, and now she’s found a subject that is uniquely hers — one that she’s emotionally attached to, that she’s excited to render in a style and medium that feels right, not like one she’s trying on.

“I have always liked to draw more than paint, and I just feel so much more comfortable doing that,” she says. “When I was a little girl, I was not exposed to paint media. When I was a little kid, I just colored with crayons, and I kind of just kept on doing that.”

Even as she continues in this phase of her life and art with these landscapes, Seagle can’t help but think of her childhood. “Just thinking how ironic it is that my parents were all about trees, too. My father worked with trees at his job as a forest ranger and my mother loved to take photographs of trees. It’s just kind of natural that I’ve just kind of slipped unintentionally into this little niche here.”

But it’s a niche Seagle plans to stay in, perhaps one that’s been in her genes all along. “I have spent most of my career doing color pictures for illustrations magazine and book illustrations,” she adds. “And now I’m doing what I want to do.”

“Of This Moment” is on display at the Medicine Factory. It features drawings and watercolors by Jeanne Seagle and paintings by Annabelle Meacham, plus works by Matthew Hasty, Jimpsie Ayres, Alisa Free, Claudia Tullos-Leonard, Anton Weiss, and others. Hours are Thursday, June 6th, noon to 6 p.m.; Friday, June 7th, noon to 6 p.m.; Saturday, June 8th, noon to 4 p.m.; and Sunday, June 9th, by appointment only. To schedule an appointment, email art@sylvanfinearts.com. Seagle will give an artist talk on Saturday, June 8th, at 1 p.m.