There are numerous examples of political artists — from Théodore Géricault, Pablo Picasso, and Glenn Ligon to Barbara Kruger, Wangechi Mutu, and the Guerilla Girls. Their works use imagery and performance that the viewer can readily identify as making a statement — on civil rights, the normal conventions of beauty, or a significant event like the bombing of the Spanish town in the 1930s (Picasso’s Guernica).

The role of politics is not as clear with non-objective work. This art is often self-referential where the abstract forms are only usually unintentional metaphors to the larger world.

Memphis painter Melissa Dunn is aware of this. The colors and the titles of her work allude to certain images or reference certain events, but “Ultimately, it is a visual experience, and the viewer has to take responsibility to connect with the work,” she says. Being in the studio is a private, intimate time for her where she is constantly asking herself, “Why does art matter?” She wonders, “How does going into the studio alone and thinking about basic shapes ever going to contribute to the greater good of society?”

Dunn continues, “There is a cultural war going on right now, people are anti-science, anti-intellectual, and I am doing the only thing I know how to do to fight this: work in the studio.”

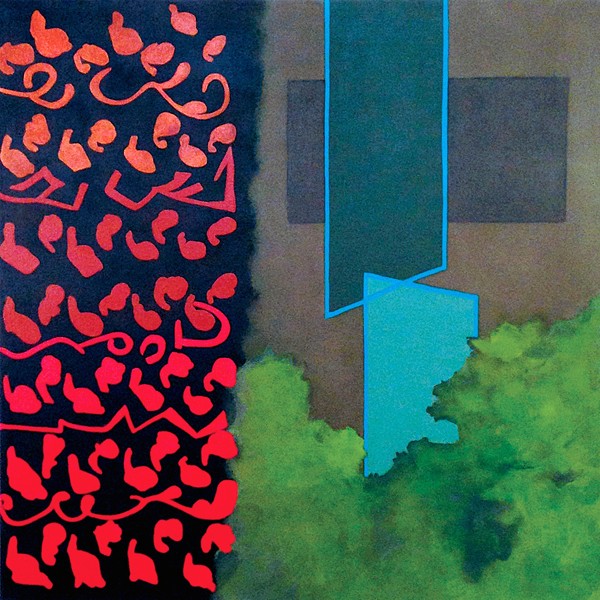

The pieces that comprise “Love Song,” showing at L Ross, are separate ideas, not variations on a theme, event, or previous work. The only constant is the potential for the viewer to connect to the work through the basic visual language she uses to create the shapes, color, line, and form. She has a borderline neurotic process of gathering and hoarding source material, obsessively drawing, redrawing, and drawing again every possible composition based on this source material. Dunn then uses small elements that she finds interesting from these drawings to construct the larger paintings.

She has sketchbook after sketchbook filled with writings ruminating where this cultural war is headed, stream-of-consciousness prose about a particular painting, color, or idea, and thoughts examining quotes from artists like Kerry James Marshall and Helen O’Leary. Because of this cultural war, she states, “Devoting one’s life to this basic visual language has complete purpose.”

In thinking about the current political situation, Dunn wonders if there is a place for love in our society. “Song,” as it is used in the title of the exhibition, refers to how we absorb music and let it flow through us. With art, it is different. “Visual art has to be analyzed,” she says. “The commodity and the experience with art is different, and this difference makes it more serious.”

Unlike previous work where Dunn felt compelled to completely fill up the surface of the painting “in order for it to have legitimacy,” these current works are more open, calmer. There is a certain serenity in the work which is as intentional as the ambiguous titles.

Standing in Dunn’s studio and looking at Trixie, Pancho and Lefty, I could not help but to sing silently to myself Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard’s version of Townes Van Zandt’s song, thinking about Mexican revolutionaries and the revolutionaries that are needed in today’s divided times. Can we count on artists to bring us together?

For Dunn, talking about things like why art matters, where love fits in, and how it connects us does not seem cliché or sentimental. Instead, talking about these things and how it relates to the act of making and engaging feels like acts of resistance. “Making art has never felt more political or necessary than it does right now,” she says.

One of O’Leary’s quotes seems particularly relevant right now: “One act of art is to document our being here, what it is to be alive now. We each must navigate our way; listen to what the times are asking of us but also do what allows us to hold onto our humanity.”