David Krog looked up to the chefs when he was a busboy.

“They were so proficient at their craft, a craft that I knew nothing about but definitely wanted to,” he says. “I wanted to be a part of that pirate group of bad boys.”

Ten years later, Krog was a chef at high-profile restaurants. He prepared intricate dishes such as foie gras torchon — even though he’d already drunk six beers and a pint of Jack Daniel’s. “You know what kept me alive in those kitchens all those years? Just straight muscle memory,” he says. “My brain wasn’t firing correctly.”

His career peaks included being chosen by actor Morgan Freeman to open the old Madidi restaurant in 1999 in Clarksdale, Mississippi. His lows included having seizures in the kitchen because he hadn’t had a drink for three hours.

Krog, 43, who is three-and-a-half years sober, now creates French-inspired Southern cuisine as executive chef of Interim Restaurant. He will be a participating chef in the Memphis Food & Wine Festival October 14th at Memphis Botanic Garden.

“We were very excited to add him to the roster,” says Nancy Kistler, the festival’s event planner, director, and one of the founders. “I think he brings a lot of talent. The dish that he’s going to prepare for the festival is going to be crazy good.”

Krog was born in Tampa, Florida, and says he was “pretty wild” as a kid. He hated school and loved the outdoors and skateboarding. “I had a lot going on in my head,” he says. “I just couldn’t sit very well. I still don’t sit well, which is a good thing.”

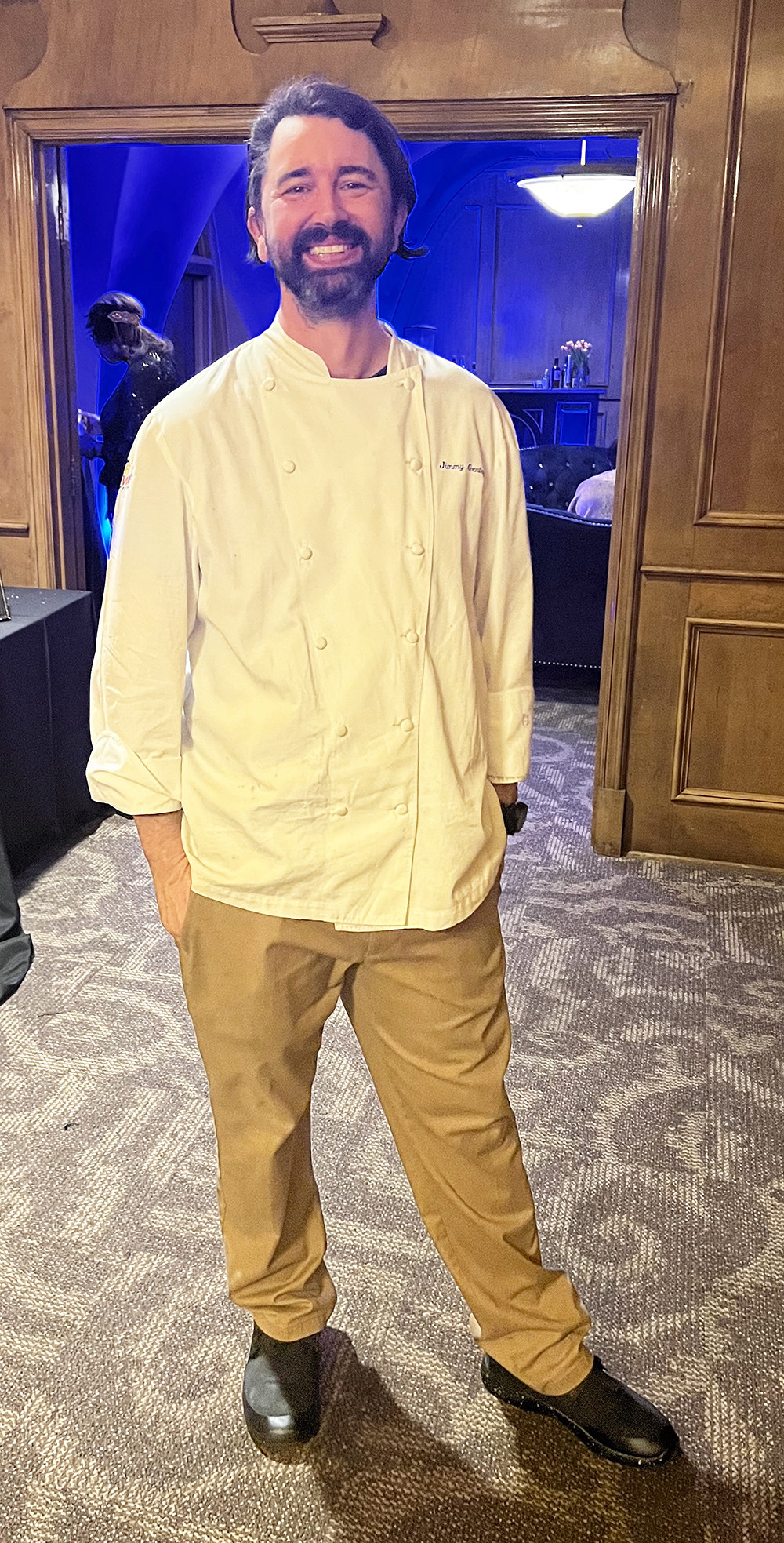

More than just muscle memory — Chef David Krog keeps his cool and serves up “pretty food” as the executive chef at Interim Restaurant.

He fell in love with the kitchen while pouring water at an Italian restaurant. “I took a pay cut from water boy to become a dishwasher. And from doing the dishes, they let you cut onions. And on and on.”

In 1992, Krog moved to Memphis, where most of his family lived. He worked at a couple of restaurants before enrolling at the Memphis Culinary Academy. After he graduated, Krog landed a job at the legendary La Tourelle restaurant, where he worked for two-and-a-half years.

Then, in 1999, Freeman, who often ate at La Tourelle, called Krog and asked if he wanted to help open Madidi. “It was a life-changing money offer,” Krog remembers, “and it was a life-changing career opportunity.”

Before taking the job, Krog talked to Bill Luckett, Freeman’s business partner at Madidi, on the phone. “I told him that I had 26 hours of tattoo work. My ears were stretched 9/16ths, and I had nine piercings. I didn’t think that I wanted to drive an hour and 15 minutes for him to look at me and tell me that this was not going to happen.”

Krog got the job. “I was way over my head.” But, he adds, “I was too ignorant to be scared.”

Krog began experimenting with drugs when he lived in Clarksdale.

“That was the beginning,” he says. “That was where I had no guidance. I was the executive chef of this restaurant. I’ve got everyone in the world telling me I’m this badass and all of this, and I was just drinking heavily.”

Krog just drank beer at that point. He drank a lot of it, but he continued to excel at his craft. “I was pulling it off,” he remembers. “I was getting great reviews.”

Then, after a hernia operation, he became hooked on painkillers. “They were Lortabs,” he says. “I could afford them, and the source was there.”

Krog never worried about getting in trouble for his substance abuse. “I used to always say, ‘When you’re talented, people always afford your habits.'”

He eventually went into rehab, but his drinking and his opioid abuse continued. “I was drinking back then from the time I woke up until the time I went to bed.”

Then Krog began making management mistakes. “Not that any 27-year-old makes the best decisions anyway,” he says. “But you couple in all the booze and my ego and it was destined to come crumbling down.”

He ended up quitting his job at Madidi in 2003: “I left because my ego and my addiction were all wrapped up into this bad thing, which didn’t get any better.”

Says Luckett: “David was the most talented, pure chef we ever had.”

Krog then worked at restaurants in Oxford, Mississippi, before returning to Memphis in 2005, where he got a job working for chef/owner Jason Severs at Bari Ristorante.

Then, during a party at a friend’s house, Krog tried heroin for the first time. After that, he says, “I just drank and did drugs — low dosage — all day long.”

His habits didn’t stop him from cooking and creating dishes. “I was on heroin,” he says. “If the dosage was right, I was at my creative peak. Or at least I thought I was. But it just was not going to work. My lifestyle was not going to work for [Severs].”

Krog went to a psychiatrist because of his opioid abuse. “I ended up on suboxone, which is a drug they give you to come off of heroin,” he says.

He then landed a job as executive chef at The Tennessean, a Collierville restaurant housed in train cars, but his troubles followed him. “I had some ups and downs there. I drank too much on a couple of occasions.” When that restaurant went out of business, Krog took a job at a country club. He drank six beers before work, a 32-ounce beer on his way to work, and whatever he could sneak during work.

“I drank at work. I had to,” he says. “If I didn’t, I would have seizures.” The seizures, which happened if he didn’t have a drink every three hours, often left him unconscious on the floor with his tongue and lip bloody.

Then, in 2010, Krog got a phone call from Erling Jensen, chef/owner of Erling Jensen: The Restaurant. He said, ‘You don’t work where you work anymore.'”

Krog met with Jensen. “He said, ‘How is your drugs?’ And I said, ‘I’ve been clean since ’09.’ Which was the truth. And he said, ‘How is your booze?’ And I said, ‘On my own time.’ Which was a complete lie.”

Jensen knew he was lying, Krog says. “You can’t hide it. But he hired me.”

Working in Jensen’s kitchen was hard work. “It sucks when you’re drunk, half-drunk, and everything. But I was able to maintain some level with him because I really wanted to be there. I was a fan of his food. I felt that the food that he put out was honest. Even drunk, I was smart enough to pay attention to what this man was doing because I wanted to get this from him. So, I think of Erling’s as a finishing school for me on a lot of levels.”

And Krog says, “He saw something in me that I had lost a long time ago. He would call me out for stinking like booze. And I would blame it on the night before, knowing that I drank three beers before I got to work. And he would sometimes bust me drinking kitchen wine.”

But Jensen kept Krog. “He kept letting me get higher in the ranks,” Krog says. “I think part of his thinking was the more responsibility that he gave me, the better I would be. But I could only do that for a little while.”

Krog didn’t get better. “I was so sick and physically addicted to alcohol that I had seizures at Erling’s.” But, he says, “I was also tough as nails. And I think Erling liked that about me. I was not afraid to go to work. I was on time.”

Over the next three years, Jensen whispered in his ear, “He’d say, ‘You need to do some soul searching,'” Krog remembers. “Or he’d pull me aside and tell me to straighten up: ‘You’ve got to watch your drinking. Your lifestyle.'” By this time, Krog was drinking 18 beers and two pints of Jack Daniel’s a day. “It took so much work for me to stay level. I’d get up to pee, and I’d have to take a shot of Jack Daniel’s to go back to sleep.”

Everything came to a head at the restaurant. “Erling fired me after a shift for drinking on the job. He was more pissed at me than I’ve ever seen in any man.”

Jensen told Krog to get out. “I was so angry with him. I rolled up my knives, and I didn’t say anything. I didn’t leave with a bang. I went straight to the beer store.”

Krog hit rock bottom. Krog had met his future wife, Amanda, at a bar. She was also an alcoholic. He had a violent seizure while they were driving to Thanksgiving dinner at his mother’s house. “We had to have booze delivered to the car.”

Amanda went to a treatment center. Krog got a job at an after-hours bar. “Inside of me, I really wanted to get sober, but I didn’t know how.”

After her treatment, Amanda “came out and she’s fresh. She’s beautiful. She looks better than ever. And I’m like, ‘I want that. I want that right there. I don’t know how to get that, but I want that.'”

Amanda drove Krog to a detox center.

“They medically detoxed me,” he says. “They give you medicine so you don’t have seizures.” He was free to leave, but he stayed to finish the treatment. “I wanted to be better. I wanted my craft back. I wanted the respect.”

Krog hasn’t had a drink since March 9, 2014. His last drink was “the last shot of Burnett’s blue top vodka in the parking lot on my way to detox. I’m an alcoholic. True alcoholic. It’s a chemical thing. And if I’m not, I will not try to test that.”

Chef Mac Edwards asked Krog to work sauté at his Farmer restaurant. Krog told him, “I don’t want to be around the kitchen. I’ll drink. I’ll do drugs. That’s what I do. That’s what that place does to me.”

Edwards said, “You’ll be here at 2 Saturday.”

“He had all the faith in me that I would be able to step right in there and be okay,” Krog remembers. But he was terrified: “All that drunken muscle memory was gone. I couldn’t do what I had done for 20 years. I was re-learning how to hold my knife.” After six months, Krog’s friend, chef Duncan Aiken, told him he should call Jason Dallas, who was executive chef at Interim. “He said, ‘You guys would get along. You both have similar styles. You both put out pretty food.’

“Well, I hadn’t put out pretty food in a long time. In my head I could do these things. But I could not execute them.”

Krog met with Dallas. “I said, ‘I am an alcoholic. I don’t drink. And I don’t do drugs. And I have only not drank and not done drugs for six months.'”

Dallas hired him.

“When I first got here, I looked like I was scared to death,” Krog says. “This kitchen can be intimidating.” But Dallas let him grow “as fast as I wanted to.”

Amanda and David lost their first child, who died at 28 weeks old. “We lost a baby in sobriety, and we’re together. We just got stronger and stronger and stronger.” Krog saw Jensen for the first time at the baby’s funeral. “He said, ‘You should be damn proud of yourself.'”

A little over a year ago, Krog became Interim’s executive chef. He hires as many young line cooks as he can, “teaching lifestyle, integrity — being the same person here as you are out there. And trying to get them before they get to a point where booze and drugs look really good.”

Last September, he and Amanda were married. In May, they had a baby girl, Doris Marie.

“At a year sober, I went and had my physical,” Krog says. “My liver count came back perfect. Kidney function perfect. Blood sugar perfect.”

He bought a home in East Memphis. “I don’t want to go to another city. My wife is here. My family is here.” He says he wants to be part of the upswing of the Memphis culinary scene.

“David was always a joy to work with in the kitchen,” says Dallas, now sous chef at Cru, a French restaurant in Moreland Hills, Ohio. “I look back at some of the great times in the kitchen together. It’s been incredible to watch him grow.”

Jensen recommended Krog for the Memphis Wine & Food Festival. He admires Krog’s “intensity in the kitchen” and his “attention to details.” And, Jensen says, “I value his his friendship a whole, whole lot. He’s a straight-up guy. Honest. Hard working. I’m very proud of him.”

“The future is bright,” Krog says. “But it’s contingent upon me doing what it takes not to drink. Because if I drink, as they say, my entire life could fit in a shot glass.”