The year 2017 will forever be a significant year in Memphis history for a pair of statues that came down. Let’s make 2018 (or at least 2019) a significant year for a statue we erect.

I’ve been campaigning for years now to see Larry Finch in bronze, a larger-than-life Memphian we lost too soon. (Finch died in 2011 at age 60 after being confined to a wheelchair for almost a decade following a stroke.) After years of uncomfortable and divisive debate about statues that represent a form of history to some and racial oppression to most, let’s make Memphis better by saluting one of this city’s great unifiers with the ultimate, perpetual tribute.

Larry Finch’s credentials for such an honor? After starring at Melrose High School, Finch chose to play basketball for his hometown college, then known as Memphis State University. This was not a blue-chip recruit choosing to join a winner. Memphis State finished the 1968-69 season (Finch’s senior year at Melrose) 6-19, the previous season 8-17. But Finch and his Melrose running mate, Ronnie Robinson, felt they could transform a program. And with the arrival of coach Gene Bartow for Finch’s sophomore season — his first playing for the varsity, as freshmen were not then eligible to play — a program was indeed transformed.

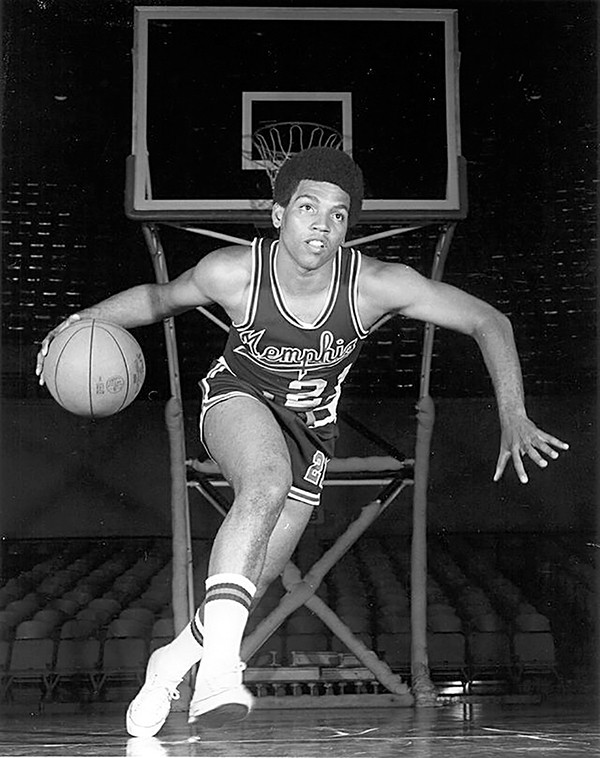

Larry Finch

Having gone 6-20 without Finch in 1969-70, the Tigers finished 18-8 in 1970-71, made the NIT with a 21-7 record in 1971-72, then secured the status of legends by reaching the 1973 NCAA championship game. Finch finished his playing career with a school-record of 1,869 points. The only three men currently above him on the Tiger chart needed four years to pass Finch’s total. His career scoring average of 22.3 points per game remains a Memphis record, unlikely ever to be broken.

Finch was an assistant coach for the next Tiger team to reach the Final Four (1984-85), then coached his alma mater for 11 years, guiding the likes of Elliot Perry, Penny Hardaway, and Lorenzen Wright. He’s one of only two men to win 200 games at the Tiger helm and fell one victory short of a third Final Four in 1992.

Those are Finch’s credentials as a basketball player and coach. But he deserves a statue as much for the when of his life as the what. Finch had just completed his junior season in high school when Martin Luther King was killed at the Lorraine Motel on April 4, 1968. The ensuing years were ugly, divisive, and painful, TIME magazine going so far as to label Memphis “a decaying Mississippi River town.” Integration efforts felt forced, perhaps because they were. School busing proved to be a disastrous experiment.

Amid all the social discomfort, Larry Finch thrived. And a town without a major-league sports franchise found a team around which to rally, as one. Finch was as Memphis as the Mississippi River, and the life he brought this region is precisely the opposite of decaying.

How do we get Finch’s statue built? And where does it go? The plaza at FedExForum would be a great spot, though I’ve heard nonsensical protests: “Finch never played for the Grizzlies. He never played in FedExForum.” A statue of Cool Papa Bell stands today in front of Busch Stadium in St. Louis, and Bell never played in the major leagues, let alone for the Cardinals. Might the Grizzlies step up and spearhead this movement? They’d sell more tickets, not fewer, with a statue of Larry Finch in the background of fans’ pictures. (If not the FedExForum plaza, put the statue in front of the new Laurie-Walton Family Basketball Center, the palatial training facility for the program on the Park Avenue campus.)

As for how . . . contact your favorite Memphis booster. This remains a small town. Anyone remotely close to the Tiger program knows a booster with deep pockets. Surely enough could be collected to pay the right sculptor to bring Larry Finch (and his magnificent jump shot) to life once more. The handsome statue of blues legend Bobby “Blue” Bland that now stands on Main Street cost upwards of $50,000. This can be done. And it should be done. Memphis has cleared itself of imagery that divided for decades. Let’s create an image that will unify and inspire for decades to come.

Frank Murtaugh is managing editor of Memphis magazine.