The Yida refugee camp sprawls as far as the eye can see, a tangle of makeshift huts made from the baked red clay of South Sudan, thatch roofs, and whatever bits of metal or plastic builders can salvage. Ten years ago, this was a pastoral village of 400, nestled between the Nuba Mountains in the north and the fertile wetlands of the White Nile in the south. Today, its inhabitants number more than 70,000 desperate people who have fled the warplanes of Sudanese dictator Omar al-Bashir.

Mark Hackett, a filmmaker and activist from Memphis, sits in a partially rebuilt church interviewing a Sudanese woman. The smell of charcoal fills the still air, as the woman struggles to describe the day militiamen from the north snuck into Yida and burned the church, which had been constructed by refugees displaced by al-Bashir’s campaign of ethnic cleansing in the Nuba Mountains.

“She was just crying,” recalls cinematographer Josh Boyd. “There was absolute silence in the church. In an area like that, where it was surprising how not-emotional people are, when people get emotional, it really gets you. They’ve seen so much, and they’ve lived so much, that when they finally do let go and cry … it’s not like how I cry when my ice cream falls off my cone.”

Hackett, Boyd, and three others have traveled halfway around the world to this obscure corner of Africa to film a feature-length follow-up to Hackett’s 2014 short documentary, Lost Generation of Sudan. “It’s about the consequences of conflict; about what it’s like to live in a refugee camp for five years, not knowing when you can get out,” Hackett says.

Mark Hackett speaks with education officials in the Yida Refugee Camp.

Sparks of Interest

“I got into filmmaking sort of accidentally,” Hackett says.

The Memphian says his worldview was shaped by his parent’s painful divorce when he was in sixth grade. By the time he got to Bartlett High School, he says, “I was a pretty jaded individual.”

During his senior year, a racially charged incident in the school led to Hackett being falsely accused of plotting violence. “I spent the night at Juvie, a 16-year-old, middle-class white kid. Not a lot of those down there,” he says. “The injustice I learned about there wasn’t about what was done to me. I met other kids down there — kids who were doing bad things because of the environment they were born into. They weren’t given a choice. Being down there changed the way I saw the world.”

In 2007, al-Bashir’s murderous campaign in the Darfur providence of Sudan commanded international attention. Hackett was attending the University of Memphis, intending to pursue a career as a chef. “There was a Sudanese speaker at U of M who talked about what was happening in his country. I thought it was the mother of all injustices. The Sudanese government was trying to wipe out entire ethnic groups that stood against the government’s vision for the country. Genocide is the crime to top all crimes. In Sudan, it’s been going on for over 25 years.”

Hackett dropped out of culinary school to devote himself to his new cause. He became acquainted with the community of Sudanese who had found refuge in Memphis and joined the Save Darfur Coalition.

“We were raising awareness and pushing some U.S. and international policies towards Sudan in hopes of making things better.”

He and his colleagues traveled the country, speaking to churches, schools, civic organizations — “pretty much anyone who would listen” — urging people to get involved. “There was a lot of empathy. Memphis was a unique place to do a lot of this advocacy work, because there are a lot of Sudanese people here.”

Failed State

Back in Africa, the slow-rolling humanitarian disaster dragged on. In 2011, the stalemated conflict officially ended when South Sudan became an independent country. But hope for a brighter future ended quickly, as an al-Bashir-backed insurgency threatened to tear the nascent country apart. The Nuba Mountains, whose inhabitants included a half-million Christians and a roughly equal population of moderate Muslims and those who follow the area’s traditional shamanistic religions, had sided with the South but ended up on the north side of the border. Al-Bashir’s army regrouped to push the infidels out of the country, but the Nuba were ready. When military victory proved impossible, al-Bashir resorted to what Hackett calls “genocide by attrition. If you can’t kill the people, you take away their means to live.”

Villages were bombed to rubble, wells poisoned, crops burned, livestock slaughtered. Sudanese regulars and Islamist militias engaged in systematic mass rape. “People were pulled from their homes, shot in the streets, burned alive. If you were an ethnically black Nuba, you had a target on your back.”

Nuba refugees streamed to the relative safety of Yiba. The situation was grim, but the people were hopeful. “They’re the only group in Sudan who have been able to stand up to the government and survive,” Hackett says. “The longer this conflict drags out, that hope is going to disappear.”

Ground Truth

The 2008 financial crisis, the election of Barack Obama, and the fallout from the failed Iraq War diverted media attention from the intractable war in Sudan. But to Hackett, and thousands of other refugees and international activists, the continuing horrors in Sudan were unacceptable. They searched for new, long-term solutions. “Could the U.S. go in and get involved on the ground and make things temporarily better? Yeah. But the minute we leave, it’s going to get a lot worse, because there’s no mechanism in place to hand over to the Sudanese.”

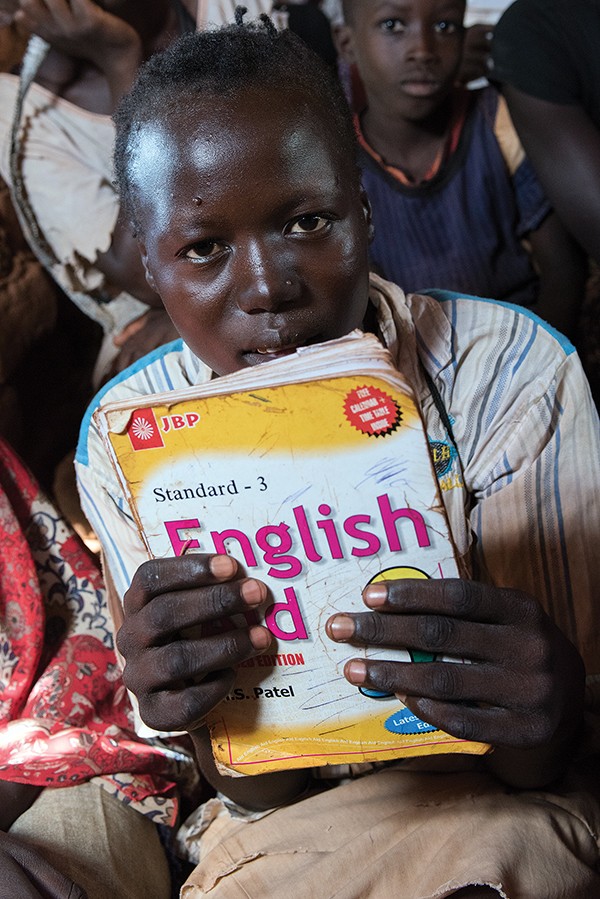

Hackett formed a new nonprofit, which he dubbed Operation Broken Silence. “We do emergency relief work, community leadership training, some other things,” he says. “But education is our primary focus, because if there’s a silver bullet, that’s it. Right now, in just the Yida refugee camp alone, there are over 30,000 kids without a classroom — a total generation missing out on their future. If those kids can be educated, there will be a window of opportunity in the future when the dictatorship falls. Dictatorships are not sustainable, by their very nature. When that window appears, those kids will have an opportunity. If they don’t have any education, they will never have that chance.”

In 2012, Hackett organized his first trip to South Sudan. “It was the most terrifying, exhilarating, emotionally draining trip. If there was one thing that surprised me, it was the people I met there. I thought I would be meeting people who were just completely shell-shocked and didn’t know how to move forward with their lives. I found the exact opposite. Everyone from rebel commanders to ordinary members of the community had ideas about how to fix Sudan. They welcomed us with open arms. They were very willing to tell their story. … I thought I would find victims, but instead I found survivors. Tough people who were actually pushing forward with solutions.

“Rather than just visiting the refugee camps, we decided to cross the border and go to one of the conflict areas. I took a camera on that trip, just to take pictures and document things. We did a lot of interviews when we were there. We weren’t planning on making a film, but we came back and thought, ‘Hey, we have all of these great interviews and footage of communities being bombed.’ So we put that together into our first film.”

Across the Frontlines was made with the help of filmmaker Josh Boyd. “I’ve known Mark Hackett since I was 10 or 11,” Boyd says. “Operation Broken Silence is close to his heart, and it’s hard not to latch onto something like that when you’re close.”

Photographer Jacob Geyer shows a group of children their photograph

The shoestring documentary was an unlikely success. “I was absolutely stunned at how it was received,” Hackett says. “International Studies professors wanted to show it to their students. Churches wanted to screen it. Once people could actually see what was happening, people were more likely to make donations or call their Congressman and tell them to support this or that bill. I discovered that not only was this the key to getting and keeping people involved, but that we could actually have a real impact on the ground. If we can do this bigger and better, we can do everything else bigger and better. Visual storytelling makes explaining what we’re trying to do easier … As opposed to us being the story, we become the microphone to let the Sudanese tell their own story.”

Lost Generation

In 2014, Hackett asked Boyd to accompany him to Africa for the follow-up to Across the Frontlines. Boyd says he was excited to go, but wandering into an active war zone gave him pause. “We wanted to instill a message of hope, because it’s all about these kids. They fear for their lives every day, so we can suck it up for two weeks to show that they’re still smiling.”

Once in the South Sudanese capital of Juba, however, things didn’t go as planned. Canceled flights ate up valuable time. “South Sudan has very few drivable roads. If you want to travel somewhere in the country, you pretty much have to fly.”

Finally, a Nuba leader gave them a tip. “He told us that a couple of hours south of there was a refugee camp. They’re all from the Nuba Mountains, and about 70 percent of them are kids under the age of 16.”

Operation Broken Silence arrived in the camp before the U.N. and witnessed unthinkable suffering. “We met moms who were looking after 20 or 30 kids. Most of the kids were orphaned or didn’t know where their parents were. No classrooms at all. That was when we realized how big the education crisis was. And that was one of the smaller camps, but there were so many kids there. So that’s when we figured out what the film was about. Anyone who knows anything about Sudan knows that the Sudanese government has committed serial genocide. We all agree this is not a good government. Maybe we need to quit talking about that and look at how that is impacting ordinary people in Sudan.”

Lost Generation of Sudan screened at Indie Memphis last fall. “Lost Generation was a very specific film with a very specific call to action,” Hackett says.

It proved to be a powerful fund-raising tool for Operation Broken Silence. “We make these films to fund-raise so we can provide education tools and pay the teachers,” Boyd says. “We’re trying to solve the problem. We’re not just raising money so we can make another film.”

Return to Yida

“Yida is sort of a microcosm of what’s wrong with Sudan right now,” Hackett says. “No schools, people who don’t have jobs, people displaced by the conflict. We wanted to go to Yida to get eyewitness interviews about what’s happening. But it’s also where most of our classrooms are. In Yida alone, it’s estimated that there are 20,000 to 25,000 kids. We’ve only put 700 of those kids back into a classroom.”

The teachers Operation Broken Silence supports are all local. “Before the war started, there were about 200 schools in the Nuba Mountains. Now there are fewer than 100, and none of them are functioning anywhere close to capacity. The schools that were destroyed, almost all of the teachers escaped, alongside the kids. They’re the only ones who understand the cultural context, and they understand what these kids have been through, because they’ve been through it, too. They’re better than any teacher we could bring in.”

Director of photography Josh Boyd photographs children in South Sudan

Cameramen Jay Geyer and grip Aaron Baggett rounded out the film crew. Photographer Katie Barber came along to capture stills. Barber, a wedding and portrait photographer, says her husband encouraged her to go, because he knew she wanted to “take pictures that matter, pictures that will make people think of the world differently.”

Operation Broken Silence departed for Africa in late May. After 30 hours of travel, the team landed in Juba, where Barber got her first exposure to the chaos of the South Sudanese capital. “No one wears uniforms, and everyone is yelling at you in Arabic,” she says. “I’m the only woman, so everyone is staring and pointing at me. I was jet-lagged and terrified.”

After a day to get their bearings in Juba, the team flew to the Yida refugee camp in an aging, single-engined Russian transport dating from the Soviet era that was so hopelessly overloaded Geyer had to sit on a stool in the aisle. “That was the first time I saw Mark worried,” Barber says. “He’s a very even-keeled person. It was like being in a tin bucket hurtling through the air. I’ve never been so happy to be in a refugee camp in my life.”

Once in Yida, Hackett contacted local elders and camp officials to get permission to film, but every day was fraught with risk. “When you’re walking around a refugee camp with cameras, and you’re the only white people there, you stand out. Soldiers tend to get antsy when strange people start taking pictures of them,” Hackett says.

“We wanted to know what it was like on a normal Friday, Saturday, and Sunday in Yida,” Boyd says. “When you wake up, where do you go? What do you do? We were talking to this one guy who was building a house. He was putting out clay bricks to bake in the sun. We asked him how long he thought it would take to build it. He said he thought about a year. The people there, yes, they’re seeking refuge, but they’re also making a life. That’s what we wanted to show.”

The team filmed in the 100-degree heat from sunup to sundown for five days. Early in the shoot, they visited the school Operation Broken Silence is funding. “The students knew we were coming,” Barber says. “Their teachers brought them out, and they stood in a giant square and sang to us. They sang how we are the people of Sudan, the children of Sudan. Thank you for coming, thank you for being here. That was the only moment on the trip where I lost it. I was trying to take pictures, but I couldn’t see. I think I was just surprised that they were so happy that someone was listening to them, that somebody actually cared. They don’t think anyone cares.”

Keeping Hope Alive

After battling heat exhaustion and waterborne illness (“I know how to get to the pharmacy in Juba now,” Boyd says.) the team returned with a terabyte of audio and video and more than 4,000 still images. Hackett and Boyd are editing the raw material into a feature-length documentary, tentatively titled Yida.

After eight years of immersion in the problems of Sudan, Hackett says his commitment has only intensified. “It’s the Sudanese people. They’ve been through so much. Things have happened in Sudan that make the things happening in Syria look like a walk in the park. A lot of the stuff the Islamic State is doing, the Sudanese government perfected those tactics decades ago. And the Sudanese have been going through this for almost three decades now, and they’re still some of the most genuine and driven people you’ll ever meet. They haven’t given up on their country.

“The refugees who came over to Memphis in the early 2000s — a lot of them would love to return home one day if things got better. Once you’ve met them, heard their stories, it’s impossible to turn your back on them.”

[slideshow-1]

To learn more about how you can help, visit OperationBrokenSilence.org.