Introducing the Justice Project:

Injustice is a problem in Memphis — in its housing, its wealth-gap, its food deserts, its justice system, its education system. In 2018, the Flyer is going to take a hard look at these issues in a series of cover stories we’re calling The Justice Project. The stories will focus on reviewing injustice in its many forms here and exploring what, if anything, is being done — or can be done — to remedy the problems.

Nathaniel Crawford has a lot going on. The 17-year-old senior at the Memphis Academy of Science and Engineering is a South Memphis native who grew up in the Glenview neighborhood before moving to East Memphis, where he lives with his mom and younger sister. Crawford’s a competitive athlete who boxes and runs track. He recently enlisted in the U.S. Army Reserve and is getting accustomed to the idea that he’s leaving for Murfreesboro this fall to enroll as a freshman at Middle Tennessee State University.

In addition to all of this, Crawford runs an event-planning business called Party Hardy, and with the help of a group called LITE Memphis, he’s looking to grow his brand and meet potential clients and investors. “I’m playing chess, not checkers,” he says, and you only have to hear a little of his spiel about combating negativity with entertainment to know he means it.

In some ways LITE — an acronym for Let’s Innovate Through Education — is similar to other business accelerators and incubator programs that exist primarily to advise and guide startups. One thing that sets the four-year-old organization apart is that it was born in a Teach for America classroom and nurtured in an environment sensitive to the invisible barriers excluding communities of color.

LITE’s clearly stated, highly ambitious vision is to help “African-American and Latinx students close the racial wealth gap [in Memphis] by becoming entrepreneurs and securing high-wage jobs.”

Working under the principle that business needs talent and talent needs access, the organization identifies and addresses historic obstacles to inclusive urban growth during the course of eight-year fellowships. The long-range goal of a process that includes high-level internship opportunities and project microfunding is to see 25 percent of the students start businesses employing two or more people, and for the remaining 75 percent to attain high-paying jobs.

On Thursday, May 3rd, 34 students, including Crawford, get to show off what they’ve learned about selling their brightest ideas when LITE hosts its annual Pitch Night at Clayborn Temple.

Crawford’s Party Hardy brand will compete against other students’ businesses plans, including a moisturizer company, an app that connects people to an appropriate church, a multimedia marketing group scaled to accommodate small businesses, and several others. The winning company picks up a $2,500 prize to invest in the business.

Crawford says he’s more interested in the opportunity to get his ideas in front of people.

“Winning isn’t the best thing that could happen on Pitch Night,” he says. “The best that could happen is I could meet an investor.”

Freeze this picture of hope and hold it in your mind for a minute. It’s inspiring news — a genuinely uplifting story about a bunch of great kids and a forward-thinking program where 100 percent of the participants go to college. That last detail is important, because people who obtain a bachelor’s degree or higher typically earn 78 percent more than non-graduates.

Additionally, should Crawford continue to pursue an entrepreneurial path, the good news is that African-American business owners tend to have a net worth 12 times greater than non-business-owners.

But the truth is, it’s going to take lots of programs creating lots of Nathaniel Crawfords and even more systemic change to close the wealth gap in the United States. Black households in the U.S. possess only one-tenth the median net worth of white households, and have almost zero liquidity.

Education and entrepreneurship are frequently identified as the surest ways to eliminate racial-wealth inequality, but the latest poverty report authored by University of Memphis associate professor of sociology Elena Delavega paints a complicated and troubling picture that challenges conventional wisdom.

“People talk about pulling yourself up by the bootstraps, but there are no boots,” Delavega says. “So I think, as a society, what we need to do is to create boots. We need to create the basis for the opportunity to exist.”

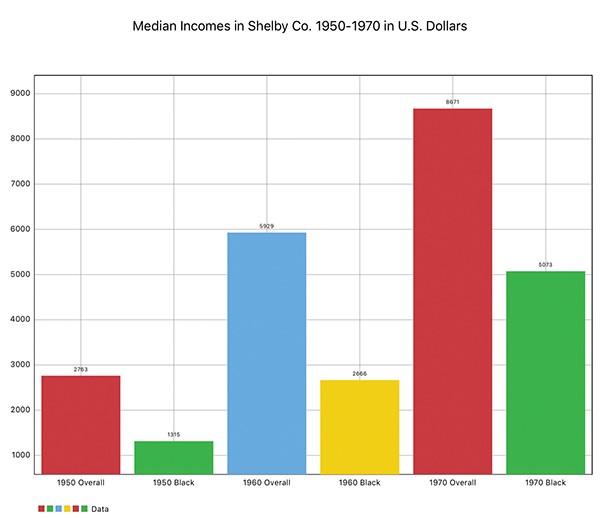

Memphis has the highest rate of child poverty in America, and it’s only getting worse. Currently, 48.3 percent of all African-American children in Memphis live with scarcity and, according to Delavega, there’s a fairly straightforward reason for that unfortunate statistic. “The children are poor because they have poor mothers,” she explained at an MLK50-affiliated Poverty Forum, where the National Civil Rights Museum rolled out “Memphis Since MLK,” a comparative 50-year poverty survey.

“This is not about marriage either,” she continued, dismissing popular narratives rooting social ills in the dissolution of nuclear families. “Poverty among married people has increased three times as fast as poverty for single mothers.” Delavega then made a request of the panel and audience: She asked everyone to hold an image in their minds: “If you see a [black] child in the street, you can flip a coin,” she said, illustrating the percentage — the yes-or-no nature — of economic security in Memphis. It was a dramatic moment in the presentation, but hardly the most alarming statistic in her report.

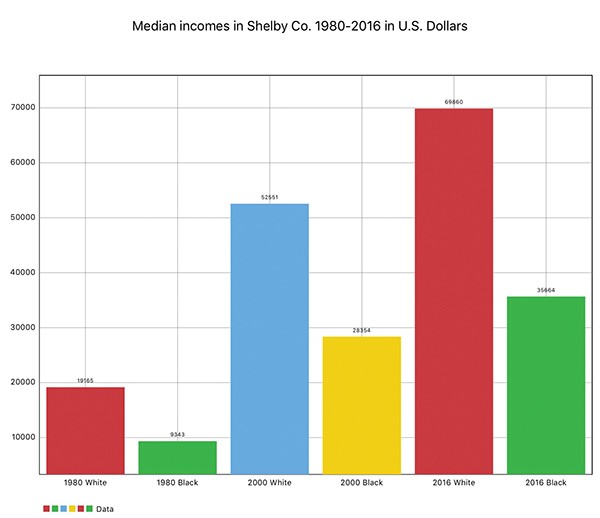

There is some good news: African-American poverty in Memphis has decreased from its peak in 1960. The bad news? The rate’s still 2.5 times greater than that of white Memphians. And, from decade to decade, earnings for African-Americans have consistently remained about half that of whites. Today, the median household income for non-hispanic whites in Memphis is $71,158, or about 11.2 percent higher than the national median. For black households it’s $35,632. Wealth, of course, is about what’s handed down, not what’s earned, but these kinds of income gaps also create credit gaps. Similar disparities are evident in black home-ownership and the average net-worth of black-owned businesses.

Compounding all the bad news in Memphis’ 50-year poverty survey was a single wicked fact that contradicts a deeply held article of faith about poverty and education. The 50-year income gap remained consistent, in spite of improved high school graduation rates among African Americans, and despite the fact that, proportionally, a higher percentage of African Americans are obtaining college degrees.

“We are told all the time: Go to school, get your degree, and your income is going to follow,” Delavega noted. “How can we look kids in the eye and say, ‘Make an effort, do what you’re supposed to do, and it will be fine,’ — when it’s just not true.”

News that gains in education for African Americans did nothing to narrow the income gap pairs distressingly with another number that Memphis journalist and MLK50 founder Wendi Thomas mined from the 2015 federal survey: Blacks comprise 51 percent of Memphis’ workforce. Whites make up 88 percent of Memphis’ executive and senior management personnel.

Coincidently, a 2016 study found that 88 percent of Shelby County contracts are awarded to white-owned firms.

On the night Delavega unveiled her 50-year report, poverty forum panelist Bradley Watkins, Executive Director of Mid-South Peace and Justice, turned his attention to Crosstown, where he described conventional wisdom regarding the enormous redevelopment project, as “the personification” of the poverty study’s findings. In doing so, Watkins described how conflicting public policy dynamics help keep the economic mobility gap in place.

“We have a city that’s said yes to any expense for Crosstown for years now, but in the same breath it has cut the [MATA] 31 Crosstown bus that connects north and south Memphis to that redevelopment,” Watkins said. “There is no implication here; that’s design. We are constantly being asked to embrace a fairytale of false positivity.”

The stories we tell ourselves about poverty and success matter. It’s difficult to change public priorities when so much of the public believes that the majority of poor people live in subsidized housing (false), receive welfare checks (false), and food stamps (false), and that poverty itself is the earned, punitive result of bad decision-making. It’s harder still when economic mobility isn’t factored into projected images of what successful cities should like.

Talia Owens, LITE fellow and sophomore at DePaul University

Travel writers love Nashville. Glowing writeups about everything from live music to locally produced liquor go viral on the regular, and in the past year, reporters have described Tennessee’s capital as one of the country’s “hottest cities” and a “city on the rise.”

The less frequently repeated story is how the same things that made Music City, U.S.A. such a great place to live — the soaring property values, cool celebrities, hot chicken, and endless media hype — have the combined effect of making Davidson County one of the hardest places in America for poor people to become middle-class.

The Brookings Institute’s Metro Policy Program released a paper last fall showing how 26 of Nashville’s top 50 occupations — 40 percent of all jobs regionally — didn’t pay employees enough to afford fair-market rent. “The number of workers spending more than 30 percent of their income on rent could fill five Nissan stadiums,” the report stated. For people struggling to survive in Nashville’s metro, living in an exciting and innovative “it” city means fair housing, transportation, employment, and high-performing schools are often beyond reach.

According to The New York Times‘ “Best and Worst Places to Grow Up,” an interactive map built around economic mobility indicators, only 12 percent of America’s metros are worse than Nashville. Memphis is part of that 12 percent. Only 9 percent of America’s metros underperform Shelby County, where the number of people paying more than 30 percent of their income on housing would fill 10 FedExForums — with a long line still waiting to get in.

In 2010, in the wake of the housing market crash, The New York Times published an article titled “Blacks in Memphis Lose Decades of Gains.” At about the same time, five million more Americans moved out of secure living situations and into neighborhoods of concentrated poverty.

“Housing that is inexpensive attracts the people with the fewest resources,” Delavega says, offering a primer on how we create disconnected communities. The story she tells has a familiar ring: High housing costs near employment centers and good schools drive people earning lower incomes to shelter-shop in depressed areas further from good jobs and better schools. Her story mirrors the the Brookings study, “Committing to Inclusive Growth,” which shows how economic mobility is most heavily suppressed in segregated communities with poor transit.

“I go back to public transportation in Memphis again and again and again, because it’s fundamental,” Delavega says, placing physical mobility near the top of a wishlist that includes: higher wages, fairly distributed housing, low-cost microcredit for minority and women’s businesses, and better access to schools and childcare for poor mothers.

“Every child who has the parents with financial resources to move to a wealthier area will do so,” Delavega says, elaborating on how the cycle works. “And every child whose parents have the time, education, or motivation to apply for a charter school or an optional school or a private school will do so, too. So who remains? The children with the greatest needs and the fewest resources — and they are now completely abandoned. So now we have this concentration of high-need [families and children] and then we say this school is failing.”

Optional programs may allow motivated families to move their children into a more favorable educational environment, but the easiest way to get your kids into a high-performing school is still to obtain property in a district where housing costs, on average, 2.4-times more than housing in lower performing school districts. As one Memphis realtor put it: “Rents in the Houston or White Station districts are going to be much higher on average than those near Melrose.”

There’s more to enrolling in a school of choice than just filling out the paperwork. And each additional step is a filter that is magnified in disconnected communities, where food insecurities pile on top of housing insecurities, and cash-strapped people are sometimes forced to choose between paying the rent, the utility bill, the car note, or catching up somewhere else.

The smallest barriers can have an enormous impact on decision-making. And nowhere is this truth more evident than the story of how Memphis became America’s bankruptcy capital and a process built to foster forgiveness and renewal became an efficiently maintained system for keeping people in debt.

In September 2017, Pro Publica, a nonprofit online news resource, published a detailed report showing how debt-strapped African Americans in Memphis were more likely to file Chapter 13 bankruptcy than Chapter 7, even though the former is more expensive and the latter frees the filer from debt. According to ProPublica, the crucial difference is that attorneys charge $1,000 up front to file Chapter 7. Chapter 13 filings may require multi-year debt repayment plans and can cost three times as much in fees spread out over time, but a “no money up front” filing option makes it more attractive.

Most filers failed to meet repayment schedules in the first year. Many become serial filers.

ProPublica’s report also noted MLGW’s unusually high number of annual utility cutoffs (about one cutoff per four users) and listed a utility debt of about $1,100 as a common driver of bankruptcy filings. It also quoted West Tennessee Judge Jennie Latta: “The way we have it set up, our culture has a lot of unintended consequences.”

“In every conversation about wealth, income disparity, and justice, we need to talk about wages,” Delavega insists, pointing to an Economic Policy Institute finding that a family of four in Memphis requires a minimum of $37,000 annually to get by — about 1 percent more than the current median income for African-American families. “If someone were to work for $18 an hour without taking any time off, 40 hours a week for 52 weeks, that comes to a little over $37,000,” she says. “So when the city approves PILOT programs on the premise that they’ll bring us jobs that pay $12-an-hour, we’re not doing what we’re supposed to do.” As the Brookings report says: No real progress can be made “if you create access to poor paying jobs or create middle wage jobs excluded communities can’t access.”

Now freeze this image in your mind and let’s return to a happier story. Talia Owens makes her desire to create a positive change part of her pitch to potential investors. The LITE fellow and sophomore at DePaul University wants people to know she’s from Memphis, a majority African-American city where a disproportionately small percentage of all revenue comes from businesses owned by people of color. “My dream is to change all that,” she says, introducing her plan to “disrupt the fashion industry” with Laude, a company that makes designer handbags accessible to people on a budget. Owens, who describes herself as a cheerleader who loves computer coding, came up with the idea when her roommate blew all of her rent money on an expensive purse. After developing the plan with LITE, she’s preparing for a soft launch of the new venture this week.

“I didn’t want to be just a person who worked a job,” Owens says. “I wanted to create jobs.”

It’s going to take change to solve Memphis’ wealth gap problems. Entrepreneurship programs and affordable handbags won’t get the job done, alone. But, like Crawford, Owens inspires. And, difficult as the circumstances are, a little inspiration can’t possibly hurt.