Robert Lipscomb has been called the most powerful man in Memphis. Power player. Power broker. Dealmaker. Deal breaker. Planning czar. Point man. Puppet master. Shadow operator. Rapist. Motherfucker.

He earned the first set of names from the powerful friends and opponents he made in a nearly 20-year career in two roles, the director of the Memphis division of Housing and Community Development (HCD) and as director of the Memphis Housing Authority (MHA). With those jobs, he directed the flow of hundreds of millions of dollars of government funding to the biggest and highest-profile projects in Memphis. This is how he — an unelected official, a behind-the-scenes operative known largely only to those in government and business — became so powerful.

The last two names in the first paragraph are from a man whose accusations have burned that power to the ground. The man, now 26 and living in Washington State, told Memphis Police Department (MPD) investigators that Lipscomb raped him. The accuser said that Lipscomb lured him into his SUV and then forced him to perform oral sex on him.

This was in 2003, according to a police report, while the accuser said he was a homeless teenager walking the streets of Memphis. The accuser said Lipscomb made him perform oral sex on him more than a dozen times after that, giving him money and promises of a better life to keep him quiet. Since the accuser’s first allegations surfaced two weeks ago, more accusers have called Memphis City Hall with similar stories about Lipscomb, city officials said. Nine by the end of last week, according to their count, though no further details have been forthcoming, either from City Hall or the MPD.

Indeed, they have gone seriously mum on what is presumably an ongoing investigation.

At this point, the allegations are just that, and Lipscomb hasn’t been charged or arrested for anything. But the stories about him have packed a powerful punch. Memphis Mayor A C Wharton, called the allegations “disturbing.” Jack Sammons, the city’s Chief Administrative Officer (CAO), called them “sickening.” MHA Chairman Ian Randolph called them “horrendous.” Lipscomb quit his job at HCD. He was suspended with pay from the MHA. Investigations have been launched into the criminal aspects of the case, of course, but financial investigators are also shining their lights on the books of every agency Lipscomb directed.

Meanwhile, the ousted Lipscomb maintains his innocence. Although he quit talking to the press under orders of his attorney, Ricky Wilkins, he was telling reporters who showed up at his front door two weeks ago that the allegations are false.

From certain points of view, it hardly matters; the damage is done.

It’s likely that, since the allegations surfaced, anyone who ever had contact with Lipscomb has completely reassessed the man who seemed to have all the puzzle pieces and knew how they fit together. Even as the allegations against Lipscomb remain to be investigated and very probably adjudicated, a new and unflattering light has begun to shine upon Lipscomb.

To many in the public, he is now like a comic-book villain walking half in the bright light of polite society and half in a private darkness with the demons that may lie there. And for all these years, if the accusations against him are true, he would have been carrying a disturbingly divided self around, one with unfettered access both to the city’s most innocent as well as to its most powerful — and with only a thin veil separating his competent and somewhat wonky public personality from an alleged private self that was both violent and profane.

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

Lipscomb overseeing slide presentation of Fairgrounds TDZ project for County Commission earlier this year; with him are architect Tom Marshall and Convention & Visitors Bureau head Kevin Kane

The Rundown

Nearly two weeks have passed since the original allegation surfaced about Lipscomb. Here’s what we know so far. First, the publicly known chronology:

Sunday, Aug. 30 — A late-night memo was sent to the press noting that a man had accused Lipscomb of rape and that Lipscomb had been relieved of duty at HCD.

Monday, Aug. 31 — Lipscomb resigns as HCD director. More Lipscomb accusers reportedly call City Hall. The MPD searches Lipscomb’s house and takes computers, folders, and a camcorder as evidence.

Tuesday, Sept. 1 — Wharton taps HCD Deputy Director Debbie Singleton to run that agency in the interim. He recommends Maura Black Sullivan, the city’s deputy chief administrative officer, to temporarily lead MHA. Even more Lipscomb accusers are said to come forward.

Wednesday, Sept. 2 — MHA suspends Lipscomb with pay, appoints Sullivan as temporary director. Sammons tells the press that Wharton’s office is going quiet on the investigation to let the MPD do its job.

Thursday, Sept. 3 — Lipscomb’s initial accuser talks with several media, including the Flyer, adding a detail here or subtracting one there, but always insisting that Lipscomb promised him a job and a house in return for sexual favors, with the relationship souring, as the accuser put it to the Flyer, after he realized “the motherfucker” was “pulling my leg.”

Tuesday, Sept. 8 — Still no charges filed against Lipscomb.

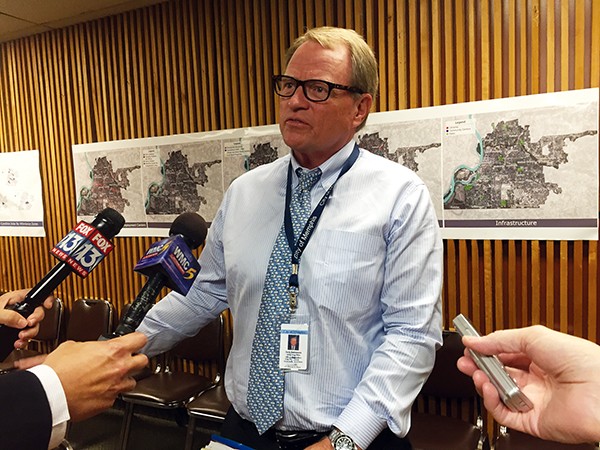

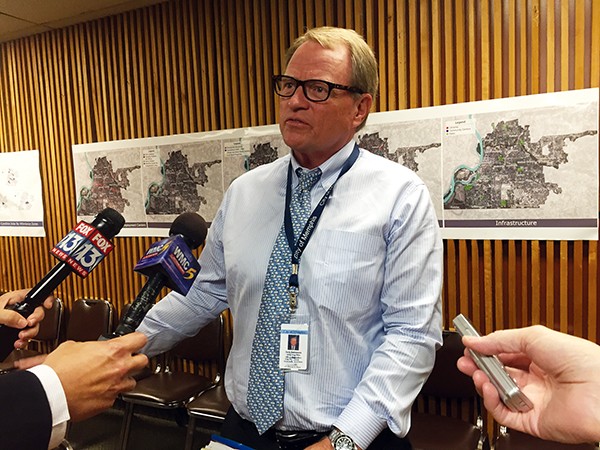

Toby Sells

Toby Sells

Jack Sammons during last week’s MHA meeting

Conversations with Wharton and Sammons, among others, have subsequently filled out these bare-boned details somewhat. The first warning signal had come into City Hall on Thursday, August 20th, with an explicit phone call to the mayor’s office from the Seattle man, who, as was later learned, was a Memphis native with a fairly lengthy police record locally.

Wharton was out campaigning, and the first to learn about the call was CAO Sammons, who had just returned from official business in Nashville. The most riveting aspect of the call, that which convinced Sammons — and later Wharton and Memphis Police Director Toney Armstrong — that the matter had to be taken seriously was the caller’s insistence that he had Western Union receipts of blackmail payments from Lipscomb.

The caller had also spoken of a police complaint he had filed against Lipscomb in 2010, one that was virtually identical to his renewed complaint in 2015. The 2010 complaint was dismissed — on the basis, police records showed, that the complainant, who was homeless at the time, could not be located.

The similarity of the two accounts, five years apart, was a convincing fact to Sammons, who explained further that the complainant chose to repeat his charges again as a form of release recommended by a therapist in Seattle.

Acquainted with the basic facts upon his return to his office, Wharton called in Director Armstrong, on Friday, August 21st, and the two of them contacted the Seattle man, who repeated his tale and also forwarded photostats of the Western Union receipts.

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

Mayor Wharton faces a press scrum about Lipscomb matter

As the mayor would explain to the Flyer, he deferred to the judgment of his seasoned police director, who decided the matter was serious enough to merit a personal visit to Seattle to meet with the accuser. Armstrong would arrange for such a visit, by himself and a group of investigators, for the middle of the next week.

Between that weekend and the Armstrong party’s return from Seattle on Sunday, August 30th, there were meetings about various pending projects in City Hall involving Lipscomb, Wharton, and Sammons. They were conducted in a business-as-usual manner, with nothing said to Lipscomb about the caller from Seattle.

But on Sunday, Armstrong and his assisting officers were back in town, and they met with Wharton and Sammons at City Hall with a full briefing on what had been two full days of investigation in Seattle. The convened group then learned that the accuser from Seattle had contacted Fox-13 news with his accusations, and a reporter from that station had called, wanting details.

That fact sped up an itinerary that otherwise might have taken days or even weeks to develop. Lipscomb was called and asked to come to the mayor’s office for a meeting, which, he apparently presumed, had to do with some hitch in one of his ongoing projects.

When he arrived, however, he found out otherwise, and arrangements were made in the tense atmosphere of that meeting for him to begin the process of separating himself from city service.

The Upshot

Heading into its third week, the Lipscomb affair has seemingly settled into an incubation mode, with dormant legal and political implications that could either simmer quietly or explode into an ever-expanding crisis.

On the legal front, the deposed planning czar’s attorney, Wilkins, an able veteran who is as familiar both with Lipscomb and with the way city government operates as anybody around, was keeping his cards — such as have been dealt — close to his chest, with the full expectation that more surprises might be yet to come.

Wilkins has made it clear, though, that he felt his client’s rights had been put in jeopardy and that he will have much to say about several aspects of what has so far transpired at some point in the future.

Meanwhile, the implications of the affair for city business and the mayoral race that was just entering its stretch drive are still being assessed.

Politically, it is too early to tell. Wharton was receiving credit in some quarters for acting quickly and decisively in dealing with the problem, once it came up. Others were prepared to fault the mayor for not seeing the situation develop under his nose or for even looking the other way from potential trouble.

Further development in the Lipscomb saga could determine which view would prevail, at a time when polls show the mayor with only a slight lead over his closest opponent, Memphis City Councilman Jim Strickland.

On the governmental front, it has long been a fact of life in City Hall that Lipscomb was calling the shots on city planning ventures, which included numerous neighborhood developments, the just-completed Bass Pro Shops at the Pyramid attraction, and a $200 million pending TDZ (Tourism Development Zone) project involving the Fairgrounds.

John Branston

John Branston

Lipscomb’s projects include the Pyramid,

John Branston

John Branston

Heritage Trail,

Bianca Phillips

Bianca Phillips

and Foote Homes.

Under two mayors, former city chief executive Willie Herenton and now Wharton, Lipscomb has been influential to the point that a common jest was to suggest that Herenton and Wharton had worked for Lipscomb rather than the other way around.

It was no joke, however, that under both his titles, Lipscomb had extraordinary power and bargaining ability, which left most members of the city council, even some who were privately critical of him, unable to say no to Lipscomb when pressed for a vote. Among other things, he had the ability to route developmental funding into their districts, or not, as he saw fit.

The Projects

No matter what was going on in his personal life, Lipscomb’s professional life as the director of the HCD and as the director of the MHA made him the point man on a number of massive city projects.

What will become of those projects — ranging from Foote Homes to the Fairgrounds redevelopment — remains to be seen, but the new MHA interim director, Sullivan, said she will be working with the new HCD interim director, Singleton, to evaluate each one in the coming months.

“Ms. Singleton and I have years of a good working relationship already and will work in concert to ensure the progress of the projects, but more importantly, the success of the city’s residents,” Sullivan said. “These projects are all multi-faceted and involve various divisions of city government. We are both currently evaluating the businesses, and the forward progress of each of these projects is a part of that evaluation.”

Here’s a rundown of a few of the projects Lipscomb’s departure leaves unfinished:

Foote Homes: Through the Memphis Heritage Trail project, Lipscomb had a vision to raze the city’s public housing projects and replace them with multi-income housing. And he saw through the eradication of five of the city’s six housing projects (and the displacement of their residents via housing vouchers) between 2001, when LeMoyne Gardens were razed and redeveloped as College Park, to 2014 when Cleaborn Homes were torn down and rebuilt as Cleaborn Pointe at Heritage Landing.

But the last housing project left in the city — Foote Homes — remains as MHA awaits a decision on the federal department of Housing and Urban Development’s Choice Neighborhoods grant. Winners of the grant are expected to be announced this month.

Kenneth Reardon, the former University of Memphis urban planning professor who led the Vance Avenue Collaborative (the group opposing the demolition of Foote Homes), believes Lipscomb’s sudden departure could put that grant at risk.

“What does Robert’s departure mean? He has been viewed as one of the most effective public housing directors in the country. So his departure, as the major planner/architect/public manager/guy who put the financing together, at this late stage, could have a serious negative effect on the city’s ability to get this [grant]. It’s hard to really know,” said Reardon, who recently moved to Boston to take a job as director of the graduate program for urban planning and development at the University of Massachusetts Boston.

At least Reardon is hoping the city doesn’t get the grant to tear down Foote Homes, which he believes is a colossally bad idea.

“We still think the city’s approach to Foote Homes is ill-conceived and certainly not the most creative and transformative proposal they could put forward, given that the number of low-income people needing deeply subsidized housing and the proportion of those who need to be downtown for employment and medical, educational reasons,” Reardon said. “Foote Homes remains a vital asset.”

Jordan Danelz, Mike McCarthy, and Marvin Stockwell of the Coliseum Coalition

The Fairgrounds: With Singleton named as the new interim director at HCD, Marvin Stockwell, the spokesman for the Coliseum Coalition, said the organization is prepared to continue talks with the city. Lipscomb was a proponent for the redevelopment of the Fairgrounds, possibly as a multi-purpose youth sports complex, and he was planning to go to the state after the October 8th election to push for TDZ status for the Fairgrounds, a move that was opposed by many. The Coliseum Coalition aims to save the long-vacant Mid-South Coliseum.

“We at the Coliseum Coalition stand ready to work with anyone and everyone to reopen and reuse the Mid-South Coliseum,” Stockwell said. “I think part of the reason that public opinion has continued to move in the direction of reopening the Coliseum is because we’ve been able to have a respectful dialogue with the city. We had that type of back-and-forth with Lipscomb, and we have every confidence that will carry forward. We’re going to pick up where we left off.”

Whitehaven: Whitehaven’s revitalization is dependent upon the area in its entirety, rather than only focusing on Southbrook Mall, which was a point of contention within the administration — and Lipscomb, who was secretly recorded earlier this year saying that some city leaders were “throwing darts” at a proposal to revamp the aging mall. Mayor A C Wharton will be heading a committee to enact the Whitehaven plan.

The Pinch District: Lipscomb’s involvement in the Pinch District development — the pressure on which has been mounting since far before Bass Pro Shops’ opening earlier this year — were first focused on making sure the hunting and fishing mega-store got up and running smoothly. During the rezoning of the Pinch District in 2013, Lipscomb was quoted as saying that the Pinch was “second priority” to Bass Pro Shops. With that complete, there’s been talk of a new hotel coming into the area. Tanja Mitchell, community development coordinator for Uptown Memphis, is hopeful that Lipscomb’s departure won’t affect the area’s redevelopment.

Toby Sells

Toby Sells

a marquee board at the Memphis Housing Authority

“We’re happy to work with any agency to get the Pinch redeveloped, because that’s something that needs to happen. The Pinch needs to come to life again,” Mitchell said.

All these, and a pending $30 million federal development grant, are potentially hostages to fortune in the uncertain atmosphere of the moment, but Wharton and other city officials have expressed optimism that all can still proceed as before.

Jackie Murray/Facebook

Jackie Murray/Facebook  Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker  Toby Sells

Toby Sells  Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker  John Branston

John Branston  John Branston

John Branston  Bianca Phillips

Bianca Phillips

Toby Sells

Toby Sells