In 2012, the hundred or so additions to Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary included “game changer,” a newly introduced element or factor that changes an existing situation or activity in a significant way, and “craft beer,” specialty beer produced in limited quantities.

As craft beer puts the squeeze on Big Brewing’s market share each year, “game changer” is an apt description for this revival of local, small-batch brewing.

Within the next year, Memphis will have three new craft breweries. And though this isn’t the first time craft beer has made a play for Memphians’ hearts, this time around big differences in the market climate promise an easier road for these upstart microbreweries. Not only are changes to state and local laws making life easier for craft brewers — the Beer Tax Reform Act of 2013 sponsored by state senator Brian Kelsey of Germantown certainly lifts some of the disproportionate tax burden from craft brewers — but also beer drinkers are more savvy.

Craft brewing entered the Memphis scene in the mid-1990s, when the first Boscos brewery and some other, less successful brewpubs opened around town. Chuck Skypeck of Boscos and Ghost River Brewing recalls a brewery in the old Greyhound station on Union Avenue, a chain brewpub on Winchester called Hops, and the Breckenridge Brewery above what is now the Majestic Grille, which still houses all the old brewing equipment. Aside from Boscos, none of these brewpubs lasted more than a few years.

In the mid-’90s, homebrewing hobbyists and beer nerds, whom Skypeck refers to as “old guys with beards,” were determined to create an alternative to the big brewing industry: Anheuser-Busch and MillerCoors. The enterprising ones among them opened brewpubs, assuming the quality product would drive demand and a market for craft beers would build up around them.

“I called it the Field of Dreams scenario,” says Brad McQuhae of Newlands Systems, a brewing equipment manufacturer in Abbotsford, British Columbia, that furnished Ghost River’s brewery. “These guys had a great idea of making wonderful styles of beer, but they weren’t marketers and they thought their beer was going to sell itself. In some cases, it worked, and, in most cases, it didn’t.”

Skypeck believes their craft beers were an unfamiliar product, and many beer drinkers, particularly young beer drinkers, weren’t buying.

“The people who liked craft beer then were old guys with beards. The younger consumer was drawn to Smirnoff Ice and flavored malt beverages and froufrou cocktails,” Skypeck says. “I told people that craft beer has to attract the 21-to-25-year-old, or it’s not going to go anywhere. The sea change that’s made craft beer grow now is that the younger consumer is now on board.”

Indeed, the demand for craft beer has been steadily growing, so much so that a second wave of craft breweries has been rolling in to meet that demand. According to the Brewers Association, in 2011, 37 breweries closed, but 250 new ones opened; in 2012, there were 43 brewery closings but 409 brewery openings, bringing the total number of breweries to an all-time high of 2,347.

“Distributors wouldn’t carry craft beer years ago,” McQuhae says. “Nowadays, we have clients starting up. They’ll have three distributors approach them and say, ‘Whatever you can make, we’ll take 100 percent.’ So you have a guy getting into business with three distributors knocking on his door and saying, ‘I’ll take all of whatever you brew.'”

With this new wave of craft breweries, beer drinkers young and old are driving the market with a seemingly insatiable appetite for craft beer.

“There are about 10 or 12 breweries that really connected with younger consumers and helped expand craft beer’s market share in those younger consumers,” Skypeck says. “And once your idea of the world of beer includes craft beer, it’s always going to include craft beer. Now, every new beer consumer when they turn 21 is a craft beer drinker.”

Twenty years into the business, Skypeck is the godfather of craft brewing in Memphis. He opened Boscos, the first brewpub in the state, in 1992 in the Saddle Creek shopping center in Germantown. While other brewpubs popped up around Memphis and shuttered within a few years, Skypeck expanded to Little Rock and Nashville and then opened Ghost River Brewing Company in 2007. Since then, Ghost River has expanded three times and is already working on a fourth expansion.

Skypeck attributes his success to two things: Memphis water (“which is really good and awesome for making beer,” he says) and his focus on the local market.

“There have been some other people who have come and gone, and very interestingly, most of those people who came and went weren’t locals,” Skypeck says. “We’re more of a local brand than a craft brand. We turn our beer over so quick, there are times we would keg a beer Friday morning, the distributor would pick it up Friday afternoon, and it would go straight down to Beale Street. You’d be having beer on Beale Street that was kegged at the brewery that morning.”

The immediacy of Boscos and Ghost River is central to Skypeck’s vision. Though pressed at every turn to expand beyond the Mid-South market, Skypeck has resisted, choosing instead to fill the ever-expanding local market. Supplying that market is plenty of work, he says, noting that Ghost River still hasn’t been able to fully meet demand because demand is so high and their brewing capacity is limited by space (hence the upcoming fourth expansion).

“Honestly, I’ve always contended this since the day we opened Boscos: Beer is a fresh, local food product,” Skypeck says. “It isn’t meant to ship around the country, much less around the world. After the 1950s and the development of the Interstate Highway System, we just got used to everything being national brands, but, before that, beer was always something fresh and local.”

(This mid-century shift likely precipitated the downfall of Memphis’ Tennessee Brewing Company, a behemoth former brewery that was once one of the largest breweries in the South. It now looms over Tennessee Street downtown, unused and in near-hopeless disrepair. Established in 1877, the brewery survived Prohibition but closed in 1954 after national brands like Budweiser swept in with national advertising campaigns, which caused local brands like Goldcrest 51 to lose favor.)

A burgeoning enthusiasm for all things local has included a demand for local beer, for an alternative to the mass-produced. With this demand for local beer has come the revival of the neighborhood brewery across the country, including in Southern cities like Birmingham and Asheville.

“There are lots of examples of craft breweries being urban pioneers and becoming an anchor for neighborhoods, especially if they have restaurants or taprooms associated with them. They help activate the streets and become gathering spots for the neighborhood,” says Tommy Pacello of the Mayor’s Innovation Delivery Team. “Like how Boscos was a pioneer in Overton Square.”

The three new breweries set to open in Memphis within the next year also follow this trend.

“All three of them have these common patterns,” Pacello says. “They’ve chosen core city neighborhoods, the key being neighborhoods. They’re not choosing to be buried in an industrial park. It’s a key part of revitalization. Is it a silver bullet? Probably not. But it’s definitely a key part.”

As for how Skypeck, who has enjoyed two decades free of local craft beer competition, will adjust to the addition of three new breweries, he remains sanguine.

“The fact that we’ve existed without a lot of other breweries is unique in the world of craft brewing,” he says. “Portland supports about a hundred. On a very basic level, they aren’t going to cut into our sales. The market’s growing so fast. It’s been demonstrated over and over in other markets in the United States that a rising tide floats all boats.”

High Cotton Brewing Company

The story of High Cotton Brewing Company begins like a joke: A lawyer, a pilot, an engineer, and a home brewer walk into a home-brew shop. From there, Brice Timmons, Ross Avery, Ryan Staggs, and Mike Lee began the whirlwind process of starting a brewery.

“As any home brewer does, we had this grand illusion, a pipe dream, that we would own a brewery,” Avery says.

“Only, Ross Avery’s way of dealing with a pipe dream is a little different from most people’s,” Timmons shoots back. “Ross already owned all the equipment.”

Eight years ago, Avery went to an auction and purchased all the brewing equipment from a former brewery. But without an actual brewery to put the equipment in, Avery’s auction purchase sat in storage. When the four finally got together, meeting through Mike Lee and his home-brew supply shop, Mid-South Malts, the fact that the equipment was on hand expedited the opening process. They purchased the space at 598 Monroe in June 2012, started construction in August 2012, and now brewing is under way. It’s impressive, especially considering all four of them have day jobs.

“It was the right mix of people at the right time,” Timmons says. “Memphis was really ready for it. Mike has been brewing here for 35 years. Ross has been at it for 20 and had all the equipment. And having a lawyer and an engineer handy was not unhelpful.”

Having a lawyer also helped when it came to changing a few laws in the process of opening the brewery.

In July 2012, Timmons, an attorney, worked with city councilman Jim Strickland and Josh Whitehead from the Office of Planning and Development to remove the city alcohol code’s food requirements for brewpubs and allow microbreweries to have taprooms on site for on-premises consumption of pints. Before the code change, brewery owners had to offer meals, including a meat and vegetable prepared on the premises, in order to open a tasting room.

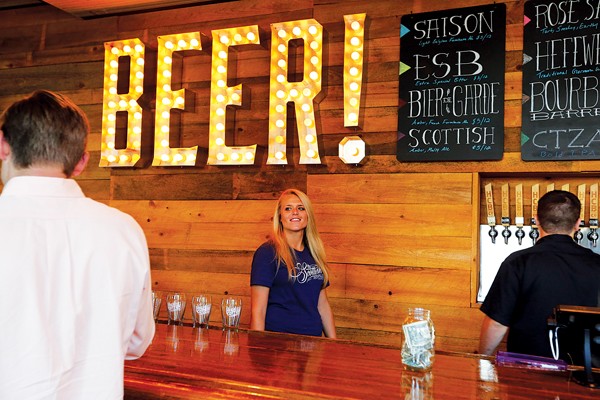

High Cotton Brewing, set to begin full-scale operations this spring, plans on eventually having a tasting room in the front of its warehouse space on Monroe. Directly down the street from Sun Studio and AutoZone Park, High Cotton’s tasting room will feature 10 to 12 beers, including seasonal and experimental varieties, large open windows, and the reclaimed bar from the erstwhile Butcher Shop downtown. But for now, the group is focused on getting kegs out the door — and into local restaurants like Jim’s Place, Hog & Hominy, Central BBQ, Ciao Bella, and Bayou Bar & Grill.

Wiseacre Brewing Company

From Davin Bartosch’s brewing degrees to Kellan Bartosch’s custom sneakers with “wiseacre” on the heels, this band of brewing brothers behind Wiseacre Brewing Company has craft beer covered from head to toe.

“We went about this in the most comprehensive way possible,” Davin says. “I over-engineer everything. When Kellan said, ‘Let’s open a brewery,’ I said, ‘Okay, let’s make sure we know how to do this better than anyone who’s ever opened a brewery before.'”

Graduates of White Station High School, the Bartosch brothers are best friends, beer lovers, and, yes, wiseacres. Kellan, 32, spent five years working on the business side of brewing, first as a distributor in Nashville and then as sales rep for Sierra Nevada. Davin, 33, has been homebrewing since he was 19, before going to brewing school in Chicago and Germany and then working for Rock Bottom Brewing in Chicago. Finally, after 10 years of planning, the two have returned to their hometown to start Wiseacre Brewing Company.

“Having a brewery is about more than having great beer,” Kellan says. “You can have awesome beer, but if you don’t have someone who knows how to move it, how to approach people with it, how to tell the story of your beer, then it’s not going to go anywhere.”

The Bartosch brothers purchased warehouse space at 2783 Broad Avenue, where they hope to have their brewery open by this fall. Like High Cotton, they are building a taproom into their brewery plans, a place for patrons to try whatever Davin has brewing. And, like Ghost River, they’re focusing on the local market.

“People want to know who made what they’re eating and what they’re drinking,” Kellan says. “Right now, people are grasping for what they can get locally. It has to do with people wanting to see their dollars go to people locally. But even the huge conglomerates are cranking out stuff that looks like craft beer, that looks like someone took care of it, when, in reality, it’s mass-produced.”

Wiseacre won’t be cranking out the same beers over and over again. Though the model has been successful for Ghost River (80 percent of Ghost River’s production is in its Ghost River Golden Ale), Davin’s brewing repertoire will be more fluid.

“We’re going to make everything. We don’t ever want to lose the experimental side of making beer,” Kellan says. “For Davin, as a brewer, it’s about inspiration, and if something comes to mind and he wants to make it, we don’t want to be handcuffed by any kind of calendar we’ve created for ourselves.”

And though they are self-professed beer nerds, the Bartosch boys aren’t looking to bring craft beer snobbery to town.

“Craft beer is so cool. I think some people are turned off by that,” Kellan says. “We don’t ever want this to be pretentious. We don’t want to condescend to people for what they enjoy drinking.”

Memphis Made Brewing Company

The Memphis Made Brewing Company T-shirt will win fans long before they taste a drop of Memphis Made beer. “When you’re bad, you get put in the corner,” the shirt reads, with a map of the state of Tennessee below it and a star to mark the spot where Memphis sits. Outside the brewery, which is located at 768 Cooper, the “I Love Memphis” mural echoes owner and brewmaster Drew Barton’s love of his hometown. Inside, Barton’s plans for the brewery bespeak a second passion.

“I started homebrewing when I was in college in Michigan, and I fell in love with it,” he says. “I bought a homebrewing book and read the whole thing cover to cover. Twice.”

He returned to Memphis to finish his schooling and got a degree in zymurgy management, the art and science of fermentation. Barton left again to work in a brewery in Asheville, the French Broad Brewery. He started out as a delivery driver, and within 18 months, he was head brewer. In 2010, after a few years running French Broad, he moved back to Memphis to work on starting his own brewery. Construction is under way, and Barton hopes to be open by late summer or early fall of this year.

“Right now, we’re looking at doing an IPA and a Kölsch,” Barton says. “Those will be our year-round beers. Everybody’s making IPAs, and IPAs sell. So, if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. The Kölsch will be something nice and new for this market. It’s a German golden ale, very clean, crisp with a slight, spicy, hot note. It’s good in the summertime, so on a hot summer day in Memphis, it’s going to be gangbusters.”

Barton is limiting the number of year-round beers to two, making room for plenty of seasonal and small-batch brews. They will also have a taproom eventually, though Barton admits that will come later in the process. As for how he feels about the influx of breweries in Memphis, Barton says there is plenty of room for more beer.

“In terms of competition, there’s room for a lot more here,” he says. “Having four breweries located in Memphis? I don’t think that’s a problem. We could have 15 breweries here. The craft brewing industry is such that we could all get together on a Friday night and drink beers and talk shop. For the most part, craft brewers help each other out. And if you’ve got good product, you don’t have anything to worry about.”

Brandon Dill

Brandon Dill  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks