A local study of poverty rates in Memphis and Shelby County confirms what most people, local and otherwise, probably already suppose to be the case.

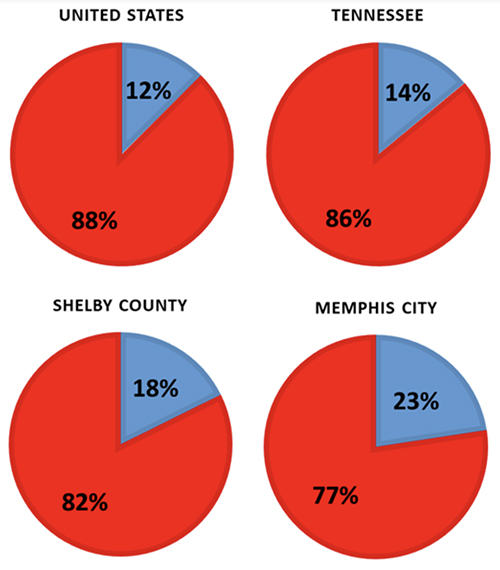

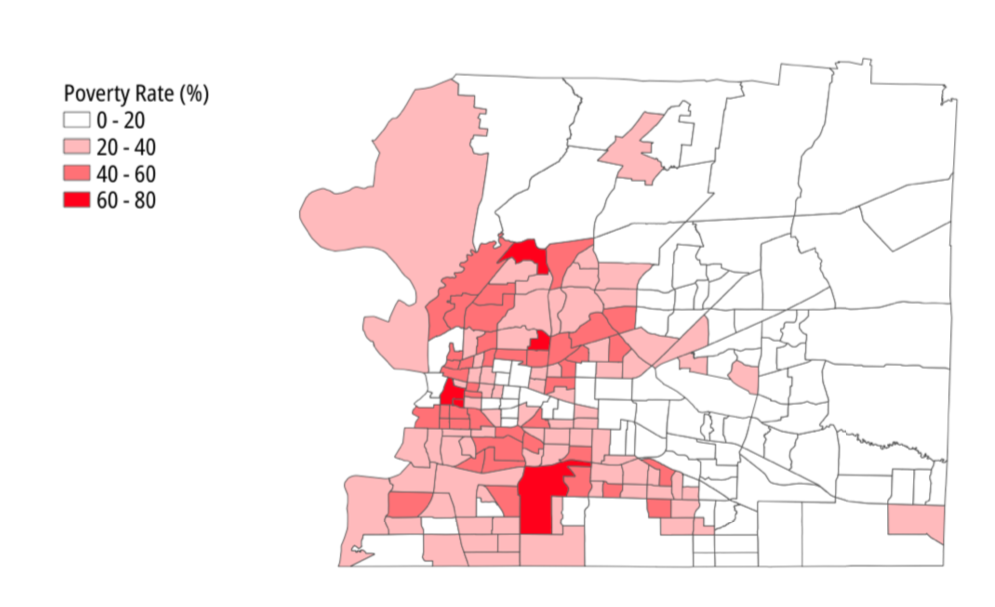

The incidence of poverty is higher in the city proper than in the county as a whole, and both Memphis and Shelby County have a higher rate of poverty than does Tennessee, while the state itself has a higher incidence of poverty than pertains in the nation.

The study, entitled 2024 Memphis Poverty Fact Sheet, was prepared by local analysts Elena Delavega and Gregory M. Blumenthal, a husband-and-wife team who undertake annual statistical reports on the incidence of poverty.

If there is a surprise in the study, based on 2020 census figures, it is that poverty rates for non-Hispanic whites are higher in Tennessee at large than in the United States, Shelby County, and the Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) of Memphis.

This might seem to suggest a rising affluence gap between the state’s white residents and its Black and brown residents. It also has implications concerning the effects of out-migration from the Memphis area.

Poverty has increased since last year, the authors find. “This is true for most groups, including children and minorities, but not for whites in Memphis or Shelby County,” they say. “Poverty for non-Hispanic whites has fallen since 2022. It also appears that the population size of non-Hispanic whites in the city of Memphis has dropped more than for other groups, suggesting that those non-Hispanic whites who left were those in poverty.”

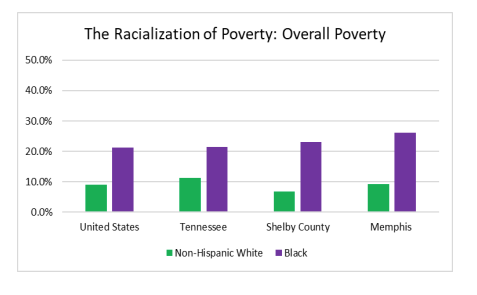

It is “not a surprise,” say the authors, that the poverty rate among minorities is higher than among whites. Indeed, they find that structural disparities based on race seem to have accelerated in 2023. “[These] disparities remain and will require deliberate efforts to dismantle. Solving poverty will require regional solutions and regional investments.”

One possible explanation for what seems to be a deepening divide locally is that the labor market in Memphis tends to consist of unskilled workers in the warehouse industry. “The lack of comprehensive, effective, and efficient public transportation also makes progress against poverty quite difficult,” the authors maintain.

“An additional problem has been that of external firms acquiring Memphis housing stock and renting it to Memphians at inflated prices, which makes it almost impossible for local families to afford housing.”

Finally, say the authors, “The divide between the city and the county, as evidenced by the racial and geographical differences in poverty, tends to deprive the city of Memphis of the funds it needs to support the region.”

Apropos the racial divide, the authors note that while Memphis ranks second in overall poverty and first in child poverty among large MSAs (urbanized areas with populations greater than 1,000,000) and second in overall poverty and child poverty among cities with over 500,000 population, it ranks significantly better when only whites are included.

Ranked only by its white population, Memphis is positioned significantly lower in the list, ranking 25th among 54 large MSAs (populations greater than 1,000,000) and 61st among 114 MSAs with populations greater than 500,000.

Ominously, the authors conclude that while the long-term poverty trend provides evidence of the structural nature of poverty in Memphis, five-year trend graphs suggest that disparities are increasing along racial lines.

• Meanwhile, on the eve of the pending presidential election, an equally fraught finding comes from a new poll by the Vanderbilt Project on Unity and American Democracy. The survey, conducted from September 20th to 23rd, based on responses from 1,030 adults across the nation, concludes that most Americans think that democracy is in danger.

More than 50 percent of Americans think that our democracy is “under attack” in the run-up to the election. The Unity Poll is meant to offer “regular snapshots of Americans’ sense of national political unity and their faith in the country’s democratic institutions,” according to Vanderbilt professor John Geer.

Memphis Poverty Fact Sheet 2020

Memphis Poverty Fact Sheet 2020  Memphis Poverty Fact Sheet Graph

Memphis Poverty Fact Sheet Graph  U of M

U of M