Only human waste and sludge stand between the Memphis Regional Megasite (MRM) in Haywood County and a possible economic development grand slam nearly two decades in the making.

Really. That’s it. At least, that’s the story according to Bob Rolfe, Tennessee’s Commissioner of Economic and Community Development (ECD). “The greatest challenge to the Memphis Regional Megasite is the lack of a wastewater discharge plan,” Rolfe told a committee of state lawmakers last year. “That is the pacing item. That is what all the site consultants tell us.”

But Rolfe has a two-pronged plan to fix that problem.

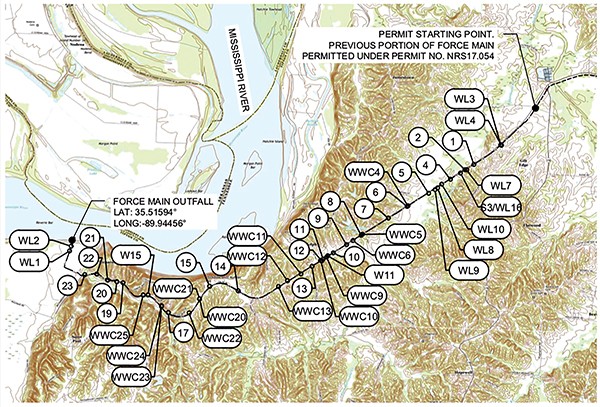

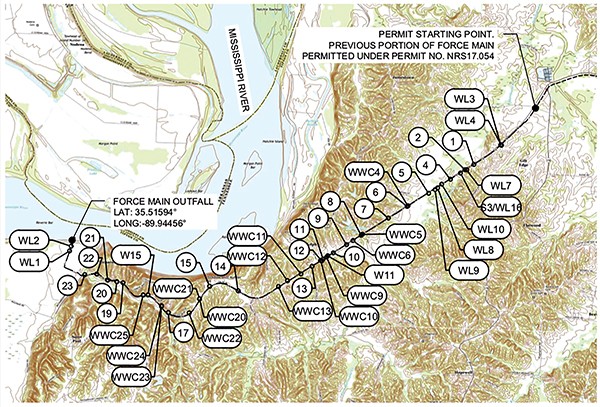

The first part: He has to get a permit. If the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation (TDEC) gives it to him, Rolfe will be able to build a 35-mile pipeline that will carry human waste and industrial waste from the site in Haywood County to the Mississippi River.

Bob Rolfe

The second part: He has to acquire land. Rolfe calls them “easements across land,” meaning, he needs to run that pipeline across property belonging to private land owners. Many along the path have already accepted money from the state to allow it to dig up their land and run an 18-inch pipeline three feet below the surface.

But some land-owners say they won’t take the money; they don’t want a sewage line running through their property. To deal with those folks, Rolfe has teamed up with Tennessee Attorney General Herbert Slatery to take their land by eminent domain. And Rolfe assured those lawmakers that Slatery has “developed a very good game plan.” Get the permit. Get the land. Bada-boom. Bada-bing. A brighter economic future for West Tennessee.

“This project would be a game-changer for West Tennessee, every county in West Tennessee,” state Senator Ed Jackson (R-Jackson) told the committee last year. “It’s so important that we get this thing, and get it right.”

We still don’t have the thing Jackson was talking about. Not yet. The long, windy road to the MRM’s success now leads to the end of that pipeline, puking waste and sludge into the Mississippi at a rate of up to 3.5 million gallons per day. If that sounds gross, remember: Folks pushing this project hope it happens really soon — the sooner the better.

The goal of the ongoing megasite saga — employing Tennesseans and bringing economic benefits to the area — still lies at least three years away, ECD officials said recently. The series is a slow burn. But important episodes in that series are happening right now.

Since the beginning of the process, much of the cast has changed — including three governors, four ECD Commissioners, and hosts of state lawmakers — but much of the rebellion remains. Environmentalists, Haywood County residents and land owners, and free-market advocates have pressed back against the whole project, the sewage line, and the eminent domain process, some of them for more than a decade, and they’re still on the show.

But the primary tension remains: Should we continue to pour taxpayer money ($143 million appropriated, $87 million spent, and $80 million more needed) into a project that offers no guarantee of financial return? And secondarily: What are the environmental impacts of the megasite to West Tennessee if the megasite dream is realized?

Since you wouldn’t start watching Game of Thrones on season three, let’s go back to Memphis Regional Megasite season one to catch you up.

Previously on Megasite

Then-Governor Phil Bredesen birthed the megasite in 2006, when it was pitched as a center for solar panel production. In 2009, state officials purchased the six square-mile plot for $40 million. At the time, similar megasite deals had brought Volkswagen to Chattanooga (East Tennessee) and Hemlock Semiconductor (Middle Tennessee) to Clarksville in billion-dollar deals. State officials had not brought anything even remotely as big to West Tennessee.

In 2009, Bredesen said he wanted to take federal stimulus funding and build a $30 million solar farm on the megasite plot, again in hopes of making Tennessee a hot-bed of the solar industry. Haywood County Mayor Franklin Smith told WMC Channel 5 at the time that, with the solar farm, “the governor is making a statement that he’s serious about helping West Tennessee by developing our megasite.”

The solar farm opened in 2012. It now produces enough energy to power 500 homes for a year.

Governor Bill Haslam was elected in 2011. By 2014, he asked for and was awarded $27 million to reroute State Highway 222 from the site and connect it to the interstate. Haslam said the site would need a total of $150 million in taxpayer investment before it could attract a major automaker to the site.

At the time, the Haslam adminstration was also fighting with environmentalists on a plan to dump megasite wastewater into the Hatchie River, considered one of the state’s most pristine waterways. Haslam lost that fight.

In 2015, the Haslam administration launched a new marketing campaign for the megasite. Later that year, Haslam’s ECD Commissioner Randy Boyd fretted to Nashville Public Radio’s Chas Sisk that the site’s massive size may be standing in its own way.

“Nissan, Volkswagen, Hankook, and Boeing could all fit on half that space,” Boyd told WPLN. “There was a time when people thought we could put one factory in 4,100 acres. But as it turns out today, there’s nobody that needs 4,100 acres.”

Boyd’s idea was to possibly split up the site, making it more attractive for smaller manufacturers and reducing the need to pump out so much wastewater.

By 2016, environmentalists had beaten a plan to dump the site’s wastewater into the Forked Deer River. Haslam said his team was slowly building the infrastructure needed to lure an investor to the site. His team was also exploring ways to dump that wastewater into the Mississippi River. That year, Haslam and Boyd headed to Asia on a 10-day trip to meet with manufacturers about the megasite but came home empty-handed.

Megasite dreams were dealt another blow in 2017, when Toyota and Mazda picked a megasite in Huntsville, Alabama, for a $1.6 billion plant. That facility employs 4,000 and makes an estimated 300,000 cars each year.

Rolfe, then the state’s new ECD commissioner, said the MRM was passed over because it was not “shovel ready.” But that wasn’t the first prospect to pass on Haywood County.

“Last year [2017], we had a candidate for large, international project of about 1,100 jobs and $800 million in investment,” Rolfe told lawmakers in 2018. “The major reason they decided to build in an adjacent state was that their megasite was further along with infrastructure — closer to shovel ready — with a lower cost of development.”

Rolfe said another prospect in 2016 would have brought 1,000 jobs and $450 million in investment. They built in an adjacent state because of that state’s tax structure, Rolfe said. Later in 2017, Rolfe said he would ask state lawmakers for an additional $72 million to make the site “shovel ready.” He kept his promise but later upped the total to $80 million.

That year, 2018, was a gubernatorial election year, and the megasite was a hot topic. Then-candidate Boyd said the site was already shovel ready and proposed doubling down on it. Almost every candidate — Boyd, Craig Fitzhugh, Karl Dean, Beth Harwell, and Bill Lee — told The Jackson Sun the megasite was a good project and they’d push to make it happen. Only Diane Black proposed something different. She said she wanted the 4,100 acres to be part of an agricultural hub, one that would work with the University of Tennessee in a new Agricultural Research Center.

As he left office earlier this year, Haslam told The Daily Memphian that not landing a tenant for the megasite was one of the biggest disappointments in his eight-year term. But he also kept high hopes for the megasite’s future. In that story, Haslam said the site is a big one, designed for the “big catch.”

New Governor Bill Lee told The Daily Memphian in January that he was committed to finishing the project. Later that month, Rolfe told The Daily Memphian that the project wasn’t finished but that the Lee adminstration would not seek any new money for the megasite unless they landed a tenant.

To date, $143 million has been given to the megasite project. As of October 2018, $87 million had been spent on it. While some lawmakers seemed surprised at the figure, Rolfe said $220 million has been the “consistent” number always needed to “have this campus shovel ready.”

At that joint committee of lawmakers last year, then-state-Senator (now U.S. Congressman) Mark Greene asked about ROI — return on investment. How many jobs, he asked Rolfe, would it take for the state to break even if lawmakers gave the project another $80 million? He didn’t get a direct answer from Rolfe at the time but did his own math, instead.

“If I look at an average income [of workers at the site] as $60,000 and workers spend money on things we get sales tax from,” Greene began, “it comes out to be that 5,000 jobs are necessary to get us a 20-year payout.”

By Greene’s math, the hit from the megasite wouldn’t need to just be a home run. It’d need to be an economic grand slam in the state, surpassing Volkswagen and weathering 20 years of economic booms and busts before Tennessee taxpayers ever made back their first nickel.

Competition?

Many of those interviewed for this story worried that focus on the megasite for all of these years has left neglected existing-yet-abandoned manufacturing sites such as the International Harvester plant or the Firestone plant in Memphis.

“One adminstration after another is saying, ‘This is what we’re going to do for West Tennessee,'” said Nick Crafton, who owns land in Haywood County close to the megasite. “But it’s sucking all the oxygen out of every other project across the region.

“Now, they’re talking about busting up [the megasite] and that’ll be in direct competition with the local industrial parks that these companies might otherwise be looking at.”

However, the Greater Memphis Chamber said it is “100 percent supportive” of the continued development of the megasite. Shelby County has a “serious lack of ‘development ready’ sites to begin with. Further, given the megasite’s size, it is not competition with other sites here. It’s in competition with other ‘sites of its ilk across the Southeast.'”

All of this is according to Eric Miller, the Chamber senior vice president of economic development, and a Haslam-appointed member of the Memphis Regional Megasite Authority Board.

“Our efforts as a region and state should be to make that site the premier available site in its category to help our region compete for much-needed tax dollars from new investment and jobs,” Miller said.

Plans for the proposed Memphis Regional Megasite pipeline

Down by the Water

The Mississippi River sloshes gently against a concrete boat ramp. The ramp angles into the muddy water from a wide, flat spot called Duvall Landing in Tipton County, about 45 minutes north of Memphis. A mud-splattered truck with a boat trailer sits in the chilly breeze, the only tenant of a parking lot big enough to swallow an airplane hangar. The lot is covered by a half-inch of mud, and a look at the detritus on the bank makes it clear that the river crested and receded here not long ago.

A kayak-and-canoe blog called RiverGator (www.rivergator.org) says the parking lot is a “notorious hell-raising party place amongst locals.” The description matched the evidence of discarded Bud Lite bottles, spent shotgun shells, and lighters that littered the ground, and an enormous bonfire circle.

Just north of that scene, state officials hope to snake a wastewater pipeline the width of a large pizza (18 inches) out into the main channel of the Mississippi. If the stars align, and they win that large manufacturer to the megasite 35 miles away, that pipe could send up to 3.5 million gallons a day of human feces and industrial waste into the river.

Party at Duvall Landing with the pipe going full blast, and you could clock about 145,800 gallons of shit and sludge sliding right by your bonfire every hour.

“People out here have to actually get in the water to launch their boats,” said Jo Cris Blair, administrator of the Say No to the Richardson Landing Poopline group. “Will they get sick? We have no way of knowing. Will the fish start glowing in the dark? We have no way of knowing.”

But Blair said the wastewater will destroy farmland, settling into soils after floods. It’ll also impact the local wildlife — fish, birds, and deer — and “it will really hurt the fishing and boating community.”

The Pipe and the River

Blair said the Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers are turning a “blind eye to the situation.” As for politicos, only Millington Chamber of Commerce executive director Terry Roland and state Representative Debra Moody (R-Covington) have shown any concern for it.

Another spot — about a mile north of Duvall Landing — was the original site for the pipeline’s outfall. But it was moved due to the concerns of locals who felt the waste would harm the environment.

Blair said she thinks the new Tipton County spot was picked because Memphis can’t take any more waste and Shelby Forest is protected.

Rolfe told lawmakers that TDEC helped his office pinpoint the new location and suggested they run it into the “deep channel” of the river. Standing at Duvall Landing, the Arkansas side of the river seems a mile away. Each second you stand there, more than 8.5 million gallons of muddy water slides by. If the pipeline was running at full capacity — up to that 3.5 million gallons per day — it would add an average of 40 gallons of sewage from the megasite each second.

Feed the phrase “dilution is the pollution solution” into Google, and you’ll find environmental groups telling you that it is not. There’s a loophole in the federal Clean Water Act that allows for dumping waste into certain bodies of water if they can provide specific “mixing channels.” Deep water with lots of volume can dilute the pollution and limit its effects; that’s the idea.

Does it work? It’s hard to say with the Mississippi. It’s so wild and so big that it’s been tough to make and maintain a water-quality tracking system.

In a previous story on this topic, Renee Hoyos, the executive director of the Tennessee Clean Water Network (TCWN), said that the river drains one third of the United States and has “been used as the nation’s toilet.” It was her sense that “by the time [the river water] gets to Memphis, it is in pretty bad shape.”

In 2017, she told the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Office of Water that the TCWN and nine other agencies like it had formed the Mississippi River Collaborative to track and fight pollution in the river.

“Right now, states in the Mississippi River basin pollute the river with so much nitrogen and phosphorus, that beaches are regularly closed, dogs are dying, and drinking water is under constant threat. We want a numeric standard for [nutrient pollution] nationwide. EPA has battled this problem for decades to no avail.”

The beaches Hoyos mentioned are likely those along the “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico. Pollution in Mississippi River water plumes out when it hits the gulf. The pollution helps algae grow. That algae sucks the oxygen out of the water and kills everything living there. In 2017, the dead zone was the size of New Jersey. It’s forecast to be larger this year, thanks to heavy rains.

What’s in a River?

The Mississippi River water at Memphis is already polluted. It contains chlordane, a now-banned pesticide, that — taken in high doses — “can cause convulsions and death,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It also contains polychlorinated biphenyls (or PCBs), a now-banned substance used to make capacitors, adhesives, floor finish, and more. Doses of PCBs can cause cancer and much more, according to the EPA.

As for human waste, the megasite actually has to have it. Crafton, a chemical engineer, explains that human waste naturally treats industrial waste. But Crafton says the only human waste so far is coming from the city of Stanton. It’s only 452 people, he says, not enough to treat the volume of waste from the proposed megasite. But the concern doesn’t just lie at the end of the pipeline. From end to end, the pipeline will cross rivers and streams 54 times, according to TDEC, and they could all be affected by pollution, should the pipe burst or leak.

It’s still unknown exactly what kind of pollution the megasite pipeline would add to the Mississippi River. That’s because no one knows what kind of company will eventually be on the site or what kind of manufacturing will take place there. Blair said ECD’s application does include heavy metals and “an unknown amount of hexavalent chromium.” If that sounds weirdly familiar, the same compound was the center of the Erin Brockovich case.

“We know what this particular contaminate can do to people,” Blair says. “And for them to literally say ‘an untold amount’ is beyond terrifying.”

Residents along the proposed pipeline are fighting back. Motions are ongoing in a lawsuit led by attorney Jeff Ward against TDEC. Ward is working pro bono, but the group has a GoFundMe page to help pay for other legal expenses.

The Next Step

The next episode in the megasite saga is a public hearing set for Thursday, April 25th, at Dyersburg Community College. TDEC’s early opinion of the pipeline is that it will “result in no more than de minimis [meaning trivial, or minor] degradation to water quality.” But the division will take public comments into account and the final decision will come down to “the lost value of the resource compared to the value of any proposed mitigation.”

Should TDEC grant Rolfe and his team the pipeline permit, he’s told lawmakers he’ll begin the process of taking lands (easements) from those who don’t want to sell. The process is expected to wrap up in six to nine months. If they get all those, pipeline construction can begin and is expected to take 18 to 24 months to complete.

“In the meantime, if [ECD] successfully recruits a company to the megasite, construction of the tenant’s facility on site can occur parallel to the wastewater pipeline buildout,” reads a statement from Rolfe’s office. “Under such a scenario, we could have a tenant open and operating on the Megasite within three years.”

Beacon Center

Beacon Center

Jake Giles Netter/NBC

Jake Giles Netter/NBC  Beacon Center

Beacon Center

Beacon Center

Beacon Center  TNECD

TNECD