Water defines Memphis.

Without the Mississippi River, the city would not exist at all. Its bones are formed as Nonconnah Creek and the Wolf River shape the I-240 loop. The massive Memphis Sand Aquifer below the city promises a future when so many communities face historic uncertainty.

“We are a water city,” said Joe Royer, who owns Outdoors, Inc. and can frequently be seen paddling kayaks up and down the Mississippi River. “When it snows in Yellowstone [National Park], it flows by Tom Lee Park. When you’re watching Monday Night Football and it’s sleeting in Pittsburgh, it’ll come through Memphis.”

But much of the city’s waters face threats, old and new. And a cadre of locals is organizing to fight them.

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) awaits testing results before it can pump 3.5 million gallons of Memphis water per day from the Memphis Sand Aquifer, the source of the city’s drinking water, to cool its new energy plant on President’s Island.

Citizens north of Memphis await word from state agencies to see if a site near their homes will host a pipeline that will dump 3.5 million gallons of wastewater every day into the Mississippi River.

And city officials in Memphis continue, under a federal mandate, to fix a broken wastewater system that has dumped hundreds of millions of gallons of raw sewage into local waterways.

TVA and the Memphis Sand Aquifer

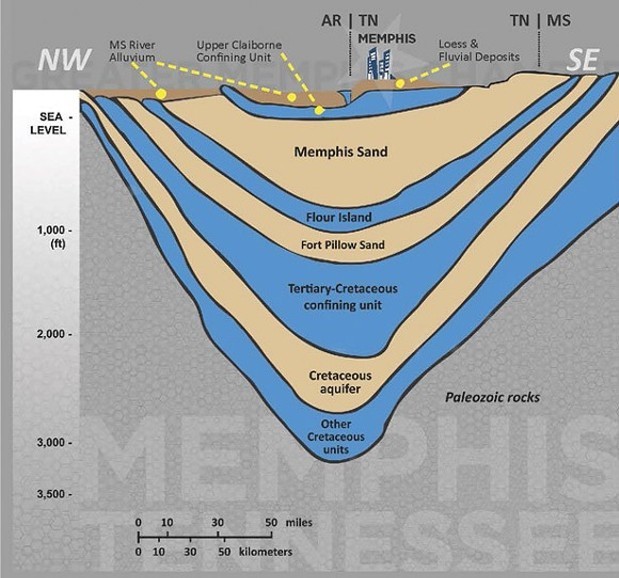

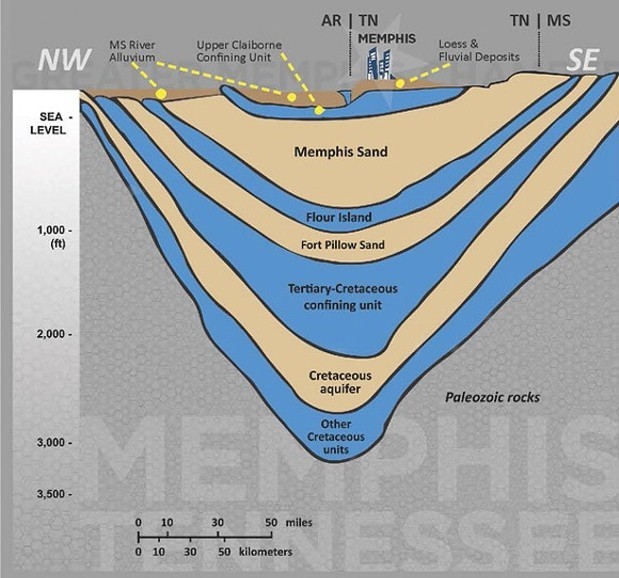

Raise the 57 trillion gallons of water from the Memphis Sand Aquifer to the surface, and it would flood all of Shelby County to the top of Clark Tower. This fact arises in almost every discussion of whether or not TVA should use Memphis drinking water to cool its new, natural-gas-fed Allen Combined Cycle Plant.

It’s a lot of water, which scores a point for TVA in discussions. And TVA’s proposed water draw wouldn’t be the biggest. (A local DuPont chemical plant sucks up 15 million gallons of aquifer water every day, according to local water experts.) But it’s not just any water.

Called “the sweetest in the world,” Memphis drinking water begins as rain in Fayette County and filters through acres of sand as it glugs slowly westward to Memphis. How slowly? The aquifer water under downtown Memphis fell from the sky about 2,000 to 3,000 years ago, according to Brian Waldron, director of the Center for Applied Earth Science and Engineering Research (CAESER) in the Herff College of Engineering at the University of Memphis. So, that water got its start very roughly between the time Homer wrote the Illiad and the Odyssey and the birth of Jesus of Nazareth.

That fact scores a point for local environmentalists who say the resource is rare, maybe priceless.

“It can be argued that 3.5 [million gallons of water per day] is a drop in the bucket, but we must never forget that our resource is finite and that individually we can be good stewards of our groundwater,” Waldron wrote in an opinion piece for The Commercial Appeal.

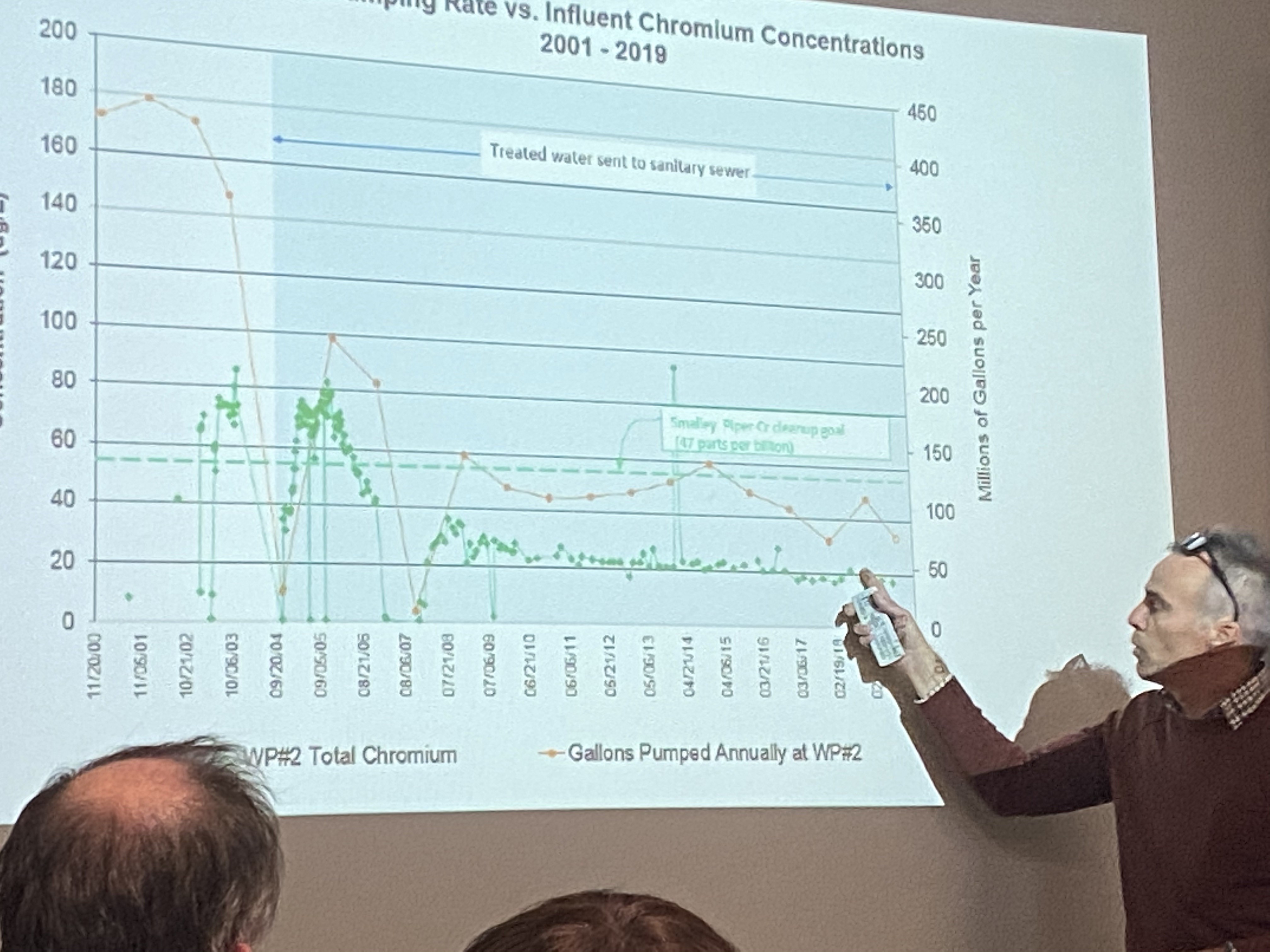

Volume, though, has rarely been the main bone of contention in the many arguments that have roiled the aquifer debate since it really got started in 2016. Environmental groups and others are more worried that the TVA’s five 650-foot wells could draw toxins into all that “sweet” water.

That argument gained new ground this summer when TVA discovered arsenic levels in some wells around the energy plant were more than 300 times higher than federal drinking water standards. Lead and fluoride levels there were also higher than federal safety standards. The contaminated water sits under a pond that stores coal ash, the remnants of the coal TVA now burns for power at the Allen Fossil Plant. That pond is a quarter mile from those five wells drilled into the Memphis Sand Aquifer.

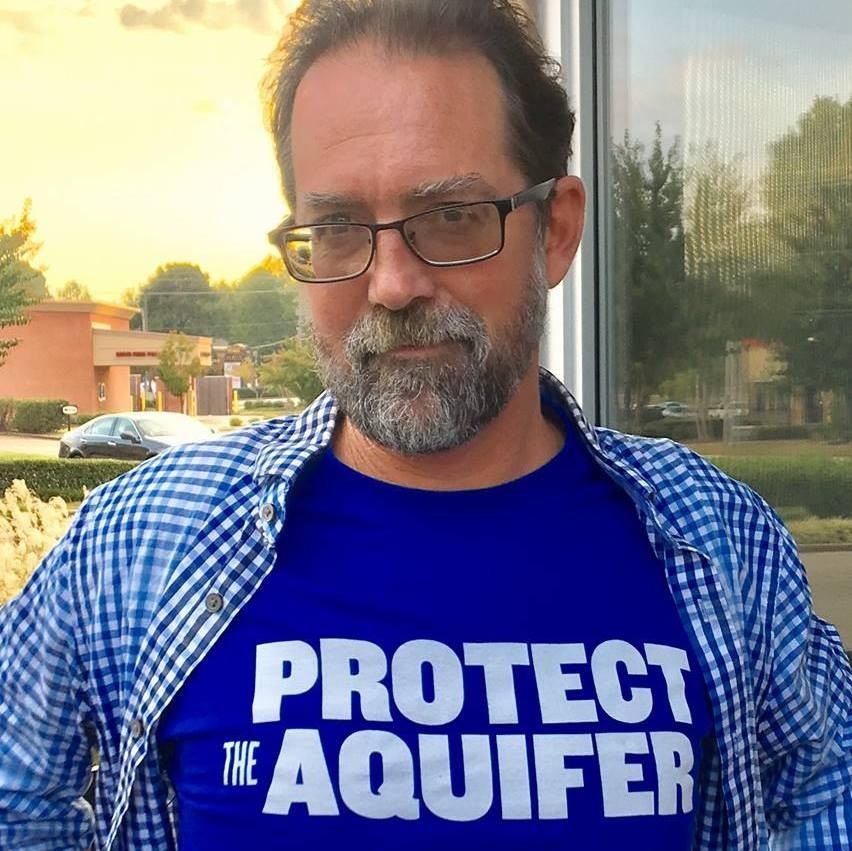

“We believe our public drinking water is our most valuable asset,” Ward Archer, founder of Protect Our Aquifer (POA), said during a water policy meeting last month. “If you really, really, really, think about it — and especially going forward — [water is] everything, and we have it in spades. But we have a lot of contamination threats.”

Archer formed POA mainly as a Facebook group in 2016 to spread the word about TVA’s plans to tap the aquifer. He formally registered the group later so it could have legal standing to join a lawsuit with the local arm of the Sierra Club to stop TVA’s well permits last year.

Scott Banbury, the Sierra Club’s Tennessee Conservation Programs Coordinator, said his core argument against the TVA wells gets down to money versus people.

“[Memphis-area customers] send $1 billion a year to TVA for our power,” Banbury said. “For them to not use wells that might compromise our drinking water would only cost $6 million. There are 9 million people in TVA-land that are required by federal law to pay the price for anything that TVA does.

“How does that math add up?” he continues. “I think it comes out to about 65 cents per year per person to make sure that we’re not messing up Memphis’ water. Sixty-five cents per person per year and you can do the right thing, the good thing.”

But TVA is required by the TVA Act (the federal law that created the organization) to provide power “at the lowest feasible price for all consumers in the Tennessee Valley,” according to an excerpt from an August TVA document called “Key Messages.”

TVA officials said in the document that its original plan (to use wastewater to cool the plant) would have required it to clean the water, adding an additional $9 million to $23 million annual cost to customers. They also looked to use water from McKellar Lake and the Mississippi Alluvial Aquifer. But all of these options, TVA said, would have added costs and risked the reliability of the new plant.

“TVA is moving forward with the best option for consumers in a responsible manner that will be respectful of the Memphis Sand Aquifer and surrounding environment,” reads the document.

Memphis Light, Gas & Water did not find elevated levels of toxins in drinking water wells close to the TVA site last year. After that, TVA ran its five wells for 24 hours, but test results are not back yet.

In response to the discovery of toxins, TVA launched a deeper investigation into the safety of its five wells in late August, contracting with experts from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and the University of Memphis to map the underlying geology around the site to better understand the movement of the groundwater (and possible toxins) there. The day after that announcement, state officials said they had a good faith agreement with TVA that it wouldn’t use the wells until after the investigation was complete.

“As a state agency, we need very convincing evidence that the contamination in the upper aquifer does not seep into the lower levels,” Chuck Head, assistant commissioner of the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation (TDEC), said at the time.

That investigation was originally projected to take months to complete. But when the plan for that investigation came out in mid-September, USGS and the U of M researchers said they didn’t have enough time to gather enough data to make a clear judgment call on TVA’s wells by the time the agency planned to fire up the plant in December 2017.

“We have committed not to use the aquifer wells until testing shows it is safe to do so,” said TVA spokesman Scott Brooks last week. “We aren’t there yet. However, construction continues on the new gas plant, which is more than 90 percent complete. Our goal is still to have this cleaner generation online by the summer of 2018.”

More help may be on the way for the Memphis Sand Aquifer. Last week, MLGW and Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland proposed a water rate increase that would yield about $1 million each year for aquifer research. About 18 cents would be added to each MLGW water meter each month for the research, to ensure our source of drinking water remains pure and is protected from potential contaminants,” reads the prosper resolution.

The River and the “Poopline”

Bottleneck blues played softly as John Duda’s paint-splotched hands worked on a single glimmer of Mississippi River moonlight. Hours of painting inches in front of a massive canvas yielded a scene of a riverboat chugging slowly toward Memphis, leaving a trail of ripples and sparkles.

Duda’s house in Randolph, about an hour north of Memphis, is filled with his work, mostly scenes of Memphis, the riverfront, and Beale Street. But his finest work may be the view from his back deck.

After he bought the house about 11 years ago, he worked for years to clear kudzu and undergrowth from his spot on the Second Chickasaw Bluff to reveal an expansive view of the Mississippi River, the bluff, and bottom lands beyond. Duda’s view belongs on postcards, but it’s in peril. He shies away from attention, but his fight against that peril has brought him into the spotlight.

From his deck, he pointed to the exact site an 18-inch pipeline that could deliver 3.5 million gallons of industrial waste and treated sewer water into the Mississippi River right below his house.

“It won’t be good,” Duda said. “I understand it’s got to go somewhere and it meets the [Environmental Protection Agency] guidelines. But to put it at the head of a town that’s been here since 1830 or before then is kind of a slap in the face to the people who live here, and the people who visit here, and recreate here.”

Earlier this year, a state plan emerged that would run a pipeline 37 miles from the Memphis Regional Megasite in Haywood County to that spot into the Mississippi below Duda’s house. The pipeline would cross at least 30 bodies of water and carry an estimated 3 million gallons of industrial wastewater from the megasite every day. The pipeline would also carry about 500,000 gallons of treated sewage from the city of Stanton, Tennessee.

State economic development officials have worked for years to prep the 4,100-acre site with $143 million in infrastructure improvements in hopes of luring a large manufacturer to the state. While Toyota-Mazda recently passed on the site, state officials promise prospective clients “the best of everything you need,” including “the best partner, the best location, and the strongest workforce.” Last week, The Jackson Sun reported that state officials said the site needs an additional $72 million to complete work there.

The idea is “terrible, terrible, terrible,” “crappy,” or, simply, “the worst,” according to Renée Hoyos, executive director of the Knoxville-based Tennessee Clean Water Network (TCWN).

“The whole [megasite project] has just gone down this road where I think people are just like, ‘well, we’ve gone this far, how about this idea?'” Hoyos said in a recent interview. “And the ideas are just getting dumber and dumber. They’ve spent all this money, and still no one is coming. It’s not, ‘build it and they will come.’ They’re not coming. So, don’t build.”

Justin Owen, CEO of the Nashville-based Beacon Center, a free-market think tank, recently called the megasite project a “boondoggle” and said that its failure so far was “legendary.”

“And the state now has to run a sewage pipe from the site to the Mississippi River, costing more money and seizing homeowners’ property along the way via eminent domain,” Owen wrote in an opinion piece in The Jackson Sun. “All for a company that is only real in the imaginations of politicians and bureaucrats in Nashville.”

Backlash to the Randolph pipeline solution began this summer. Dozens showed up to oppose the project at TDEC meetings close to the site. A Facebook group called “Say No to the Randolph Poopline (Toxic Sludge)” was organized and quickly grew. But, again, volume is not the main bone of contention in the “poopline” argument with most. It is the location.

At the exact site of the proposed wastewater pipe, sandy beaches appear on the banks of the Mississippi during its regular flow. Duda said people come from near and far to camp at the site, launch kayaks, ride horses, and sit around bonfires. During a recent visit, beer cans, clay pigeons, spent shotgun shells, and ATV tracks evidenced some other, recent recreation.

The site seemed to be picked because it’s close to the where the Mississippi meets the Hatchie River. Flows from the two would help dilute the treated wastewater and send it downstream. Duda said that plan might work when the water was high. But at low levels, an area between the Tennessee side of the river and a mid-stream island gets cut off.

“All of a sudden all of this water gets cut off, and that means 3.5 million gallons [of wastewater] will just be sitting in two, or three, or four pools down through here,” Duda said. “When it’s not mixing, they become cesspools, essentially. Whenever you go by any treatment plant cesspool area, what have they got around it? A chainlink fence with barbed wire to keep people out.”

Duda also feared the pipeline would drive away local wildlife — geese, bald eagles, deer, and more. Years of exposure to the heavy metals in the wastewater would eventually obliterate the spot for human recreation and for the miles of fertile bottomland farms around it for growing corn, soybeans, or cotton.

Environmental dangers loom beyond the spot, too, back along the 37 miles of pipeline that run from the proposed factory and the 30 bodies of water it would cross, said Hoyos.

“That pipe will be under pressure, so you may only notice a problem if it’s a big break,” she said. “But little leaks? You may not notice them. There may be a pollution event that goes on for months and months and months and you may not be able to see them.”

The crowds at the meetings, the Facebook group, and the calls to state lawmakers all delayed a decision on the proposed pipeline last month. It was enough to earn a 30-day extension for public comment on the project. One of those voices for the delay was Shelby County Commissioner Terry Roland.

“This type of discharge will certainly negatively affect the commercial and recreational fishing near Shelby Forest, not to mention the wildlife, to include 43 species on the federal endangered list, popular swimming beaches, boating camping, etc.,” Roland said in a statement at the time.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Memphis Sewers and The Waters Around Them

The feds have long been after Memphis city officials about its wastewater.

Back about 40 years or so, they forced city officials to treat it before they dumped it into the Mississippi River. Since 2012, the federal agencies have required the city to spend about $250 million over several years to fix and upgrade its weak, leaky wastewater system so the city doesn’t spill untreated sewage into the river (which we have, still, a lot). The city now operates under a consent decree for the improvements agreed to by the TCWN, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the U.S. Department of Justice, TDEC, and the Office of the Tennessee Attorney General.

In 2010, federal and state agencies filed a formal complaint against the city alleging that “on numerous occasions since 2003” the city illegally spilled untreated sewage into state and federal waters. City officials “failed to properly operate and maintain [its wastewater] facilities” and allowed “visible, floating scum, oil, or other matter contained in the wastewater discharge,” into surrounding waters.

For this, the city paid a civil penalty of about $1.3 million to resolve the violation of the Clean Water Act. It also had to devise a plan to beef up its wastewater system and promise vigilance on clean water issues going forward. But vigilance doesn’t guarantee perfection.

In March and April of 2016, for example, two sewer pipes broke. Both were associated with the T.E. Maxson Waste Water Treatment Plant on President’s Island. One was eight feet tall and another five feet tall. When they broke, they dumped more than 350 million gallons of untreated wastewater into Cypress Creek and McKellar Lake. (For perspective, the damaged Deepwater Horizon well spilled 210 million gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico in 2010.) The spill killed 72,000 fish, spiked levels of E. coli bacteria in the waterways, and left behind layers of sludge.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

John Duda’s house north of Memphis has a great view from the Second Chickasaw Bluff.

Later that year, a three-and-a-half-foot sewer pipe broke close to the M.C. Stiles Waste Water Treatment Plant north of Mud Island. Two-and-a-half million gallons of raw sewage dumped into the Loosahatchie River every day for three days.

In all of the spills, the dirt banks around the pipes had eroded and the pipes broke under their own weight. Correspondence from Memphis leaders show plans are in place to fix those pipes permanently. But Hoyos, with the Tennessee Clean Water Network, said spills like these are “not surprising.”

“You’re going to see [sewage] overflows because, as you’re tightening up a system in certain places, it really accentuates the weaknesses in other sections,” she said.

In a March 2017 letter to Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland, an official with TDEC’s Division of Water Resources said that the city would not only fix the pipes, stabilize its banks, and closely monitor all of them, the city must pay the state damages for the 2016 spills. Those damages were figured at $359,855.98 “for ecological and recreational damage to Cypress Creek and McKellar Lake, excluding damages for fish killed as a direct result of the spill.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

City of Memphis Public Works Director Robert Knecht said the city is negotiating the terms of that agreement with the state. He said his agency doesn’t like raw sewage spills, of course, but that the city is responsible for 3,200 miles of sewer lines, with 2,800 of those miles of pipes within the city limits. From them, the city’s two wastewater plants process about 60 billion gallons of wastewater each year.

Capital improvements needed for the city’s sewer system, he said, range from $850 million to $1.2 billion. While the consent decree mandated the city spend $250 million, Knecht said it’ll end up spending about $350 million simply because officials discovered about 25 percent more sewer infrastructure after the decree was signed.

The Water City

Many interviewed for this story said they would not swim in the Mississippi River, especially south of the Stiles Waste Water plant. TDEC advises that no one eat fish from the river. Hoyos said that the river drains one third of the United States and has “been used as the nation’s toilet.”

“By the time it gets to Memphis, [the river] is in pretty bad shape,” she said.

All that water, of course, drains into the Gulf of Mexico near New Orleans. There, a “dead zone” bloomed this year the size of New Jersey, the largest on record. For more on this, check out a story in this week’s Fly By, page 6.

Still, given all the perils to the city’s water and waterways, Royer of Outdoors, Inc. believes in Memphis as a “water city” and that its natural resources will be key to its future, and not just for outdoorsy types. Digital technology has given most the ability to work almost anywhere and that puts Memphis in a “real competitive environment” for workers.

“And if the salary is even close, they’ll choose to go to the most livable city,” he said.

Tennessee Valley Authority

Tennessee Valley Authority  Facebook

Facebook  JB

JB  Corey Owens/Greater Memphis Chamber

Corey Owens/Greater Memphis Chamber  Toby Sells

Toby Sells  Toby Sells

Toby Sells

Toby Sells

Toby Sells  Google Maps

Google Maps  Toby Sells

Toby Sells  Toby Sells

Toby Sells

Southern Environmental Law Center

Southern Environmental Law Center  TVA

TVA  Toby Sells

Toby Sells  Toby Sells

Toby Sells

USGS

USGS

Tennessee Valley Authority

Tennessee Valley Authority

Tennessee Valley Authority

Tennessee Valley Authority  Edwards Aquifer Authority

Edwards Aquifer Authority  Corey Owens/Greater Memphis Chamber

Corey Owens/Greater Memphis Chamber  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks