It was such a moronic statement that when it was blurted from a Memphis City Councilman’s mouth, I thought, “Is he for real?”

It was moments after the end of what had been a sadly disappointing council committee public hearing to listen to ideas about how to remedy the impasse created by the council’s vote to cut health care and pension benefits for city employees and retirees. As I scrambled to get interviews in the hallway to gather some perspective on what happened, the indignant councilman approached me, asking if I wanted to hear his solution to the whole problem. I said yes. He then declined to talk, instead cryptically uttering, “I know where you live.” He then smirked, walked away, and took the elevator down.

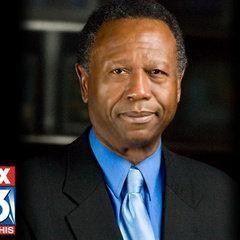

It would be easy — we in the media have done it before — to dismiss such an incident as just another cantankerous episode by this council veteran, rather than assume there was some attempt at personal intimidation involved. But, for some reason, as the day and the week went on, I really started to get angry about his remark and his audacity, as a black elected official, to level some “gangsta” innuendo at another African American.

It’s ironic that in the same month we commemorate President Lyndon Johnson’s signing of the landmark 1964 Civil Rights Bill, Memphis continues to suffer from a crisis in African-American leadership — in politics, in economics, and in education.

I remember the euphoria the black community felt when Willie Herenton became the city’s first African-American mayor. Since then, we’ve had 23 consecutive years of an African American as the chief executive at City Hall, many black majorities on the council, numerous black police and fire directors, and 24 straight years of black school superintendents. Some accomplishments have been registered: tearing down aged blighted apartment complexes to restore hope where none had existed before. We got a new sports arena and a pro basketball team. Beale Street has become a world-wide tourist attraction, and the long-awaited Beale Street Landing riverfront project is finished, even if it was millions over budget.

But honestly, look in the mirror, black and white Memphians, and ask the same pertinent question that catapulted Ronald Reagan to the presidency: “Are you and your family any better off than you were four years ago … or 10 or 20 or 30 years ago?” Statistics, including 28 percent of Memphians black and white living below the national poverty level and consistently worse than the national average unemployment numbers, say a frightening number of Memphians are worse off. Our educational system is not a model for the nation. It’s a liability for those who might consider moving here. It’s no secret we’re losing population every year, unless we want to start annexing the fish in the Mississippi River.

Is it possible that in the Bluff City’s case, the 1964 Civil Rights Act hurt us as a race of people more than it helped us? After decades of blaming the white man for the ills of society, we African Americans were given the chance to govern not only ourselves, but everyone in Memphis and Shelby County. What have we gotten in return for our empowerment? We’ve given our officials the keys to our government and too many of them have interpreted it as a sense of entitlement. They sneer when asked simple questions about their residency. Constituent service has taken a backseat to grandstanding at public forums. We have endured too many banner headlines exposing their personal problems.

The Civil Rights Act was also supposed to make it possible, by ending segregation in schools, for our children to become a part of mainstream America. Unfortunately, in doing so, it sacrificed the pride and diligence of many black teachers who had dedicated their lives and love to making a difference in the classroom. It broke up communities where people once took it upon themselves to be their brother’s keeper and his family as well.

People such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Ben Hooks, Maxine Smith, and many others in this city sacrificed much of their lives to see the day when the fight for equal rights would end in triumph. Now that fight needs to be changed and waged to use the power of the vote to find the right people to serve us — not be served — whether black or white.

By the way, councilman, I know where you live, too.