If there was a table designed exclusively for the forefathers of Memphis rap, Alphonzo “Al Kapone” Bailey would be among the artists seated at the head. With the release of several albums and compilations, he’s managed to sell thousands of units independently, and is viewed as one of the most respected artists within the underground rap movement.

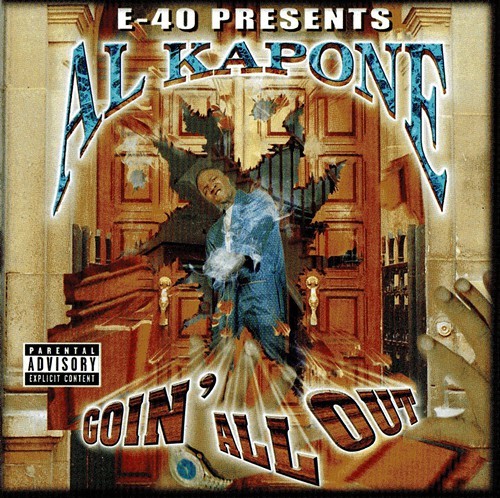

Penning rhymes since the sixth grade, Al Kapone began to obtain musical notoriety as a teenager with his song, “Lyrical Drive-by.” This led to his debut album, Street Knowledge: Chapters 1-12, which secured a spot on Jet Magazine‘s Top 20 Albums chart and solidified his presence within the Memphis rap movement. Underground albums such as Pure Ghetto Anger, Sinista Funk, the compilation Memphis to tha Bombed Out Bay, and Goin’ All Out, followed soon after his debut, and expanded his fanbase from the South to the West Coast.

Aside from creating underground classics, Al Kapone is a talented songwriter and producer. He co-wrote E-40’s “U and Dat,” Lil Jon’s “Snap Yo Fingers,” (which both charted on Billboard’s R&B/Hip-Hop section), and “Hustle & Flow (It Ain’t Over)”, the theme song to the 2005 Memphis-based film, Hustle & Flow, and more.

I got a chance to speak with Al Kapone about his music career, what attendees can expect from his performance at this year’s Beale Street Music Festival, songwriting for E-40 and Lil’ Jon, what led him to create a song that supported past Congressional candidate Republican George Flinn, rock music, and more.

Follow Al Kapone on Twitter: @AlKaponeMemphis

Follow him on Instagram: AlKaponeMemphis

Visit his website, AlKaponeSongs

Download some music from his extensive catalog here

How did you get into making music?

I was into storytelling. It went from that to writing stories to actually writing songs from the stories. When the hip-hop craft stage kinda took off, I fell in love with it. Even though I love all forms of music, I just fell in love with hip-hop to the point that that’s what I wanted to do.

I got into just the whole hip-hop scene and the whole culture. It was more than just the rap part of it, it was the DJ-ing, the breakdancing, the graffiti, the fashion. It was really the whole culture of hip-hop, but I ended up sticking with the rap side more than anything.

What made you choose the name Ska-Face Al Kapone as your rap moniker? And why did you eventually drop the “Ska-face” part?

I was living in the Lamar Terrace projects at the time, and I was looking at this old black-and-white movie called Scarface Al (Scarface, 1932), it was basically the old version of the Al Pacino Scarface.

I remember seeing that and Scarface Al just grabbed me. It was at the time when NWA was poppin’, so the gangsta rap scene was real hot. And I knew I wanted a name that was gonna be edgy, so when I saw Scarface Al go across that screen, I was like, ‘That’s it. That’s the name.’

And actually, this was before Scarface from the Geto Boys had kinda ran with his name, because I think at the time, he was going by the name Akshun. So it was before him, but that leads to the reason I ended up dropping Ska-Face because when “Lyrical Driveby” popped off for me on a solo tip, I was still going by the name of Ska-face Al Kapone. I added the Kapone part because I began noticing that the Houston rapper Scarface was starting to get popular, and when I did out of town shows, people were starting to get me confused. They were asking me where Bushwick [Bill] was. So I thought, ‘Okay, I’m gonna go ahead and drop the Ska-face part because it’s starting to create confusion.’

At what point did you know music was something that you could fully rely on as a way to provide for you and your family?

When “Lyrical Drive-by” popped off. I was working at Red Lobster at the time. When I was going back and forth to work, I started to notice cars going by blasting that song. It was like several cars, and that’s when I realized, ‘Oh shit, people recognize me now.’ That’s when I started getting calls to do more shows. At that point, I was able to leave Red Lobster and actually start doing shows full-time, and that’s when I was able to start providing for me and my family.

In 2003, you released the album Goin’ All Out on E-40’s label, Sic Wid It Records. How did you link up with E-40?

My main connection to the Bay Area was initially with this magazine called Murder Dog. They featured me in a lot of their publications, and from that, as an independent artists, I started networking with a lot of the independent artists out there. And from that, E-40 took notice, and then, he reached out to me. From the independent artists to E-40, I really established a strong Bay Area connection.

My connection with 40 came in the late ’90s. Like I said, he’s originally from Murder Dog. He just started noticing my name a lot through Murder Dog and the independent scene. He reached out to me to be apart of a compilation that he was working on at the time called Southwest Riders. It was a lot of independent artists from the West and independent artists from the South.

How did you end up signing with Sic Wid It?

After I ended up doing that compilation with [E-40], just through my connections with independent Bay Area artists, I did my own compilation called Memphis to tha Bombed Out Bay. What I did was, I took a Greyhound to the Bay. I had a cousin who was staying in Sacramento, and I still had my Murder Dog connection. So I took a Greyhound out there with all my product. I just went out there promoting blindly, didn’t know, all I had was straight ambition. I rented a car and was getting directions from people and literally driving from Vallejo to Oakland to Frisco to Sac Town [Sacramento] to even smaller towns in between, from Richmond…it was crazy. It was before GPS. I was strictly going off people’s directions from the highway, and I was actually getting there.

I ended up running into E-40 in Vallejo. It was a picnic that he was having, and again, I was out there promoting Memphis to tha Bombed Out Bay, and he just noticed, ‘Damn, dude just came all the way from Memphis and he actually has a line of people he’s signing autographs for at my picnic.’ He sent his brother over to let me know that they were going to pick me up and bring me to his house. I was staying at the Murder Dog house at the time.

His brother came and picked me up. I went to 40’s house. He was working on some music, and he said, ‘You feel like you can jump on this song?’ I was like, ‘Holy shit, he wants me to jump on a song!’ I immediately wrote a verse like in 10 minutes and jumped on the song and at that point, he was like ‘I’m gonna be reaching out to you. How you feel about signing to Sic Wid It?’ And after I came back to Memphis, he reached out to me and we made it official. He sent me a contract and we sealed the deal.

You did some writing on E-40’s album, My Ghetto Report Card. How did that come about?

That was one of those amazing times. Not burning bridges allowed me to. I wasn’t signed to him at the time. This was like some years after the contract had ended, but we kept a good enough relationship that he reached out to me when he was working with Lil’ Jon and wanted me to come to Atlanta and [work] with them on some music. It was kind of a blessing to be in that particular space and time to offer some of my writing skills, which out of that spawned the “Snap Yo Fingers” song that Lil’ Jon had.

When you’re songwriting, are you actually writing verses for artists, or are you contributing ideas?

It’s more of contributing ideas. Coming up with ideas and concepts and writing hooks to give the song the direction that it needs to go into.

What are some other albums you’ve had a hand in that people may not know about?

Off the top of my head, I know I did something on the Stomp the Yard soundtrack. I did something on the Cadillac Records soundtrack. That’s a couple I can think of off the top of my head.

You also wrote a couple songs on the Hustle & Flow soundtrack.

Most definitely. That was another one of those space and time blessings that you don’t see coming. It was all again, not burning bridges, because I knew Craig [Brewer] way before. He was doing independent films and having them distributed through Select-o-Hits whereas we were doing the independent CDs, so we knew each other from that time. And I always kept in touch with him.

I just so happened to randomly call like I normally do, and it doesn’t have to be about no business, just to reach out to people on a personal level. So I was just reaching out to him one day and seeing how he was doing, and that’s when he informed me about what was going on, that John Singleton was going to get behind the project and John was going to be in town the next day. They were looking for a particular song. John really had his mind set that he was going to let Three 6 [Mafia] do everything, but they were going to give me a chance to present something. It was almost like, ‘He’ll just check it out’ but his mind was pretty set.

I went straight to the house and wrote the Hustle & Flow theme song. When John came in town, he came to the Cotton Row studios. Me and Niko [Lyras] had just finished producing the music and I dropped all the lyrics and everything. When he came, he heard it, he said it was on point…the whole subject was on point with what they were looking for, and I was in.

From that, he wanted to hear some other songs that I had been working on personally. That’s how he ended up hearing “Whoop that Trick” and “Get Crunk, Get Buck.” He was like, ‘damn, we need to work with those songs too.”

Over the last few years, you’ve incorporated more of a guitar-infused style into your music, especially with your album Guitar Bump. You’ve also branched out and collaborated with different bands and musicians. What influenced you to take a different lane with your music after creating that more gangsta, buck sound for so many years?

My initial reason [for] going into the live zone of music rather than staying in the crunk zone was because the rest of the country made up in their mind that Atlanta was known for crunk. Even though we had the proof, nobody was going to dig into the truth enough to give us credit for it. The rest of the country saw it as we would be the followers, even though we weren’t. We were the originators. So instead of fighting against it, I wanted to do something that was uniquely a Memphis thing. I started thinking about the live sound of Memphis as far as Al Green, the rock side and everything. I started thinking, let me go more into that direction and see if I can incorporate live music with the Memphis sound and see how that would be received.

My main thing was to show the hip-hop culture of Memphis. Even though y’all don’t want to give us our credit for the sound, give us credit for at least our musical roots, and that’s really why I started going in that direction. But in the process of recording that type of music, I ended up having to perform it live, and I actually fell in love with having that band on stage. It was an amazing feeling to have all that live music. It was like another level of performing, so I kinda ran with it. There’s nothing like performing with that live instrumentation on stage.

Have you always been interested in guitars and the rock genre?

Even though I was into hip-hop earlier on, I was always into soul and rock. From Ozzy Osborne to the Black Sabbath, I was always into it. When Nirvana hit at the time, I was heavy into that. I was heavy into Metallica. If anybody really followed my music career and they listened to some of those old songs, you would actually hear songs that had the rock element or the soul element to them. It was always there but when I went with the band, it kinda stood out more.

You’re performing at this year’s Beale Street Music Festival. What can attendees expect from your performance? I read you’re working with some live guitarists for the show.

If you’ve never seen a live performance from a Memphis rap act, my goal is to always give you a concert. Not just go up there and rap the songs, I want to truly entertain you with the whole spectrum of the music—from my performance to the musicians adding the instrumentation. My goal is to give you an experience where you can walk away and say, ‘You know, I don’t really listen to rap but I enjoyed that show. That was a good show.’

An eye opener for a lot of people was when you created the song “George Flinn” that encouraged Memphians to vote for Republican George Flinn as Congressman for the state’s 9th district last year. What persuaded you to endorse Flinn?

I did it because I felt like he supported not just me, but through his station [George Flinn owns several radio stations that cater to such genres as hip-hop, classic rock, Christian, and country], he supported the Memphis rap scene.

When I go to different places, I notice that a lot of radio stations do not support their local music scene. For us to have a station here that really supports and plays local music at times when the rest of the country had kind of stopped supporting Memphis hip-hop, I just felt the need to show support to someone who was supporting the music scene that I came from.

Did you worry about receiving any backlash from endorsing Flinn?

I did think about [receiving backlash] before I did it. I didn’t feel like the black community would embrace that I was supporting a Republican. The way I saw it was, if I don’t do it, it’s not because I don’t wanna do it, it would be because of what other people think. And at that point, I realized that I didn’t want to look back years later and say, ‘I shoulda did that and the only reason I didn’t was because I didn’t want to be worried about what somebody else thought.’ When it’s all said and done, I can’t live by what other people think. And at that point, I felt like I was supporting him regardless.

You’ve released all of your albums independently. What has caused you to avoid going mainstream for so many years?

The thing about being independent, you’re pretty much in control of what you want to do [and] release. That’s the biggest thing. You have total control. As long as you know how to budget and try to keep some consistent releases out there. You can kinda maintain some pretty decent cash flow to come in. But your main thing is your freedom to record what you want and release when you want to. You’re able to design your own artwork. But it does require work. Being independent is not just the freedom. It’s a serious work ethic that goes along with it. And I always had that drive to grind. I actually love the hustle of promoting and working on that level. I also love to write and produce, so it works out for me because I enjoy that whole hustle.

I had situations where I could’ve signed some major deals here and there but it was never in my favor. The thing is, you can lose a lot signing the wrong type of contract. You can sign away your rights. Right now, I own pretty much all of my catalog, so I can release it whenever I want to. I have a whole catalog of music that I haven’t even released digitally yet that I’m in the process of releasing. If I would have signed to a particular major [label], I wouldn’t have had any rights to release none of my previous music.

What’s next for Al Kapone?

I’m finishing up this album. It’s back to the roots of that straight underground Memphis rap. I did a song called “Memphis Pride” that pretty much represented the whole Memphis rap scene. So basically re-representing the original Memphis rap sound. That early Memphis sound. I got a project representing that sound but it’s today, but it’s still that sound at the same time. That’s the next project I’m [about] to drop. I’m thinking I’m going to drop that some time in May, so look out for that.

Follow me on Twitter: @Lou4President

Friend me on Facebook: Louis Goggans