The short-term peace on Greensward parking negotiated between the Memphis Zoo and the Citizens to Protect Overton Park (CPOP) expired late last month when the last shuttle ran from the Overton Square parking garage to the park.

Memphis city officials say overflow parking will likely resume on the Greensward. CPOP says it will continue to encourage people to enjoy the Greensward. But continuing the “Get Off Our Lawn” campaign — the peaceful, sit-in style protest — will depend on the continued cooperation of all parties to find a way to keep cars off the grass for good.

Brandon Dill

Brandon Dill

Tina Hamilton (left) and her Great Dane, Dominic, relax with Allison Tribo and her dog, Foxy, inside Overton Bark dog park.

The fight for the Overton Park Greensward has cooled somewhat, especially from the tense beginning that threatened the arrest of a CPOP protestor. Now, all involved seem focused on a new, more-distant horizon that promises a long-term solution to the parking problems at Overton Park and the Memphis Zoo. They await proposals for a fix from Memphis City Hall, which are expected in a couple of months. The city’s chief administrative officer, George Little, says he’s agnostic on the solution but that all sides need to have skin in the game.

“My position is when everybody feels like they’ve got something to gain and everybody feels like they’ve got something to lose, that’s when we’re going to see some movement,” Little says. “It’s not going to happen as long as one side is like ‘I’ve got mine, you’re not getting yours.'”

The Opening Salvo

The guy directing cars for parking at the Memphis Zoo pretended not to see Jessica Buttermore. He walked right across the field to her and turned his back, stopping just two feet from her blanket on the grass. He pumped his palm toward his chest until a big, whirring SUV came to a stop just four feet from where Buttermore was reading a book.

She sat up and gave him a look, but the attendant moved on and so did the people from the SUV. None of them said a word to her or even looked her way. Buttermore remained on her blanket, sitting in bemused disbelief. Did that just happen?

More cars came as the day wore on. By the time Buttermore’s group packed their stuff, they found themselves marooned, an archipelago chain of islands in a dusty sea of parked cars. No one parking cars that day acknowledged the people on the lawn.

This incident lit the fuse for what has now been a weeks-long fight for the Greensward in Overton Park.

“It became really clear that the zoo … felt like it was their space,” said Buttermore, chair of CPOP. “They had ownership of it and we had no right to it as members of the public, when, in fact, it is a public space. At that point it became really clear that we have got to really amp this thing up.”

And they did. The day after she and others were ignored by the parking attendants, they showed up with warnings written on big signs: “Don’t Park on Our Park.”

Wind of a bigger, more organized protest planned for the Greensward the following weekend reached City Hall. So that next Saturday, Little rode by on his bike for a first-hand look.

“I felt like I was riding up and down the line in Braveheart,” Little said. “You know when the English and the Scots are on the opposite sides? I felt like I was riding up and down the line. All I needed was a shield to bang on. I mean, really? C’mon. We’re all Memphians.”

Two Sides and the Mayor

Like in Braveheart, people on both sides of the line Little saw that day believe in something bigger than themselves. Unlike most movies, there was no clear good guy or bad guy in the Overton Park parking war.

Brandon Dill

Brandon Dill

Pip Borden, 9, enjoys a popsicle during a hot afternoon on the Greensward at Overton Park.

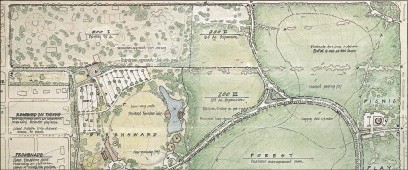

The protestors believe everyone benefits in keeping that corner of Memphis uncluttered and open to any who want a respite from urban life — as it was designed to be by George Kessler in 1901. Zoo officials believe everyone benefits if we allow parking in the Greensward because it helps a top-tier Memphis attraction that educates thousands each year and is a major tourism and economic engine for the city.

The physical stand-off between the two sides got tense that weekend. Cops were called. But they were called off by Memphis Mayor A C Wharton, who closed the Greensward to parking soon after that weekend. Shuttles were hired to take visitors from the new garage at Overton Square to the zoo, or the park, or the Brooks Museum of Art. It was going to be an uninterrupted, five-week pilot program.

But zoo officials asked Wharton to reopen the Greensward for what was going to be a busy Memorial Day weekend. He did, but only for that weekend. Then, zoo officials asked Wharton to reopen the Greensward for a major corporate event for Toyota that was going to bring in an additional 4,000 visitors to the zoo. He did, but only for that event.

The Greensward was closed every weekend until the end of June. And Wharton’s administration has been working with all sides to forge a new short-term compromise and to find that long-term solution.

So, passionate factions with claims to the same land? Frustrations coming for all the major players? Clear victories blunted by compromise? A saga that began like Braveheart has become more like Game of Thrones.

What is a Greensward?

The word “Greensward” is foreign to many — even many native Memphians — but it’s the name for the large grassy field that surrounds Rainbow Lake and the new playground on the west side of the Old Forest. It’s 21 acres from end to end and side to side. (FedEx Forum sits on less than 14 acres.)

Brandon Dill

Brandon Dill

Brian Sanders enjoys a cold drink along with (from left) Elaina Norman, Patricia Duckett, and Kim Duckett as they watch Cedric Burnside Project perform during the free summer concert series at the Levitt Shell in Overton Park.

The Greensward is at the height of its intended use on the first warm days of spring. It’s always bustling with people walking dogs, families having picnics, couples lounging together on blankets, games of Frisbee and hacky sack, drum circles, and more. It’s a large, open, natural area, which is hard to find in Memphis.

The land technically belongs to the city of Memphis. That is, it belongs to everyone in the city and is wide open for them to use it. But the Overton Park Conservancy (OPC) manages the park for the city. So, upkeep on the Greensward falls on them.

The Memphis Zoological Society has a similar management contract with the city for the 70-acre zoo and the 3,500 animals there. That contract says the city will provide parking, and for more than 20 years, that has meant overflow parking on the Overton Park Greensward.

Memphis Zoo CEO Chuck Brady calls it an “old problem” and says the zoo has been misunderstood on the issue for years, not just during the recent dust-up.

The decision to use the Greensward for overflow parking was made when the city — not the Memphis Zoological Society — managed the Memphis Zoo decades ago, Brady says. A new master plan for the zoo in 1986 called for 1,000 parking spaces to be built in front of the zoo. Neighbors complained, and that number was shrunk to 655, which the zoo has in its front lot now, Brady says. The idea then was that any overflow parking would be put on the Greensward.

Permanent parking solutions have been proposed twice by the new zoo management, Brady says. One was a new parking deck slated for the east side of the zoo. It was scrapped because it would not best perform its secondary purpose as a floodwater retention basin.

After that, Brady says zoo officials proposed building a parking lot on the strip of land on the southeast corner of East Parkway and Sam Cooper. The zoo planned to use a tram to cross the street into the park and then into the zoo. Brady said that plan was axed as city officials said they had other plans for the land.

“I bring these things up because we’ve heard a lot of criticism that we haven’t tried anything,” Brady says. “But we have been trying — not successfully, we can say that — but we’ve definitely been trying to find a permanent solution that’s doable.”

That’s part of what frustrated Brady when the latest parking controversy began a few weeks ago. But he was more frustrated because he said the zoo and the Overton Park Conservancy were “very close” on a new agreement on parking, an agreement that was scrapped in the wake of protests, shuttles, and the promised new way forward.

The basics of the agreement would have allowed the zoo to use the Greensward while they work together with OPC to find a long-term solution that would eventually yield the Greensward completely back to the park.

“The [memorandum of understanding] really outlined how we would work together over the next few years to achieve some short-term and long-term parking solutions,” says OPC Executive Director Tina Sullivan. “There was tacit understanding that OPC needed to work with the zoo on a long-term solution before we took any actions to try to remove them from the Greensward.”

Brandon Dill

Brandon Dill

Citizens to Preserve Overton Park members (from left) Naomi Van Tol, Stacey Greenberg, and Roy Barnes stand on part of the contested area of the park’s Greensward used for overflow parking by the Memphis Zoo.

Brady says he was taken completely by surprise when Wharton kiboshed Greensward parking in the beginning of the dust-up. It stung to be so close to an agreement and have it dashed and supplanted with ideas that zoo officials thought wouldn’t work.

So, the zoo issued a lengthy news release that shocked many. It accused Wharton of joining with the “protesters’ mission” and said his proposals for a fix would “lead to the demise of the zoo as we know it.”

CPOP’s Buttermore says she couldn’t believe the release made it past the zoo’s public relations department, but she’s glad it did.

“We always tell people we’re not anti-zoo,” she says. “Then this statement went out and — wow — you just did a really big favor for our campaign. We don’t have to go around really being anti-zoo because you just made a bunch of people really mad.”

And it did. Wharton issued a formal statement saying the “tone of the press release was disrespectful and inappropriate,” but he committed to continue working with the zoo and park officials to find a common solution.

“It was a strong response, and I apologized to the mayor that it was personal,” Brady says. “We’re passionate about this zoo. We built this zoo to what it is today. I don’t mean me. I mean this whole organization. We work hard every day.”

New Solutions?

Wading into the land of parking solutions for the park is much like wading into Rainbow Lake to look for something you lost. You know it’s in there somewhere but you can’t see it from the surface. You know finding it will be hard, dirty work. You’re not exactly sure where it is. And you’re not sure what you’ll bump into while you look.

Wharton outlined three solutions in May. Those solutions are the ones that drew the ire of the zoo officials.

One idea was the short-term shuttle trial. Depending on who you talk to, the experiment had limited to moderate success. Ridership was lower than expected but some thought the program wasn’t promoted enough or given enough time to catch on. Even Brady agrees that shuttles might be a part of a long-term parking solution for the zoo.

Wharton also opened up the General Services area for free parking to zoo visitors willing to walk through the Old Forest to the zoo. It was originally panned by zoo officials because the 1.2-mile round trip would make the option prohibitive for children, the elderly, or disabled. But zoo employees are now parking in the General Services area, which has freed up about 100 parking spots in zoo lots.

The final idea that came from Wharton in May is the one that likely has the most long-term traction. It’s the most expensive, most permanent, and probably toughest to execute. But it’s the one that has the most support from the city, the zoo, and the conservancy.

Wharton proposed a $5 million, 400-space parking deck to be built somewhere on zoo property or near the zoo. Zoo officials quickly said a garage needed to be 600 spaces and the cost was likely closer to $12 million. But how big it should be and how much it will cost are almost secondary questions.

Brandon Dill

Brandon Dill

Childbirth educator Sarah Stockwell (left) talks with Mary Beth Best of Birth Works Doula Services during an event at Overton Park benefiting Postpartum Progress, a nonprofit that supports new mothers with mood or anxiety disorders.

City and zoo officials agree the toughest questions for a garage are: Where will it be built? Who will pay for it?

The easiest and quickest location seems to be the city’s General Services area that fronts East Parkway. But that land has been promised to the backers of a museum devoted to the works of photographer William Eggleston. Little says the city is now in a development deal with that group and that the negotiations pretty much lock up the property. Messing with part of that deal could mess it up completely, Little said, especially when it comes to luring private investors.

A parking deck could also be located where the zoo’s maintenance facilities now stand. But where would those facilities go? Again, the General Services area could easily stand in but that puts the Eggleston deal at risk.

A deck could even be built on top of existing zoo parking but that would, of course, take away valuable parking spots. And the deck would have to pass some pretty high design standards to blend into the zoo, the park, and the surrounding neighborhood.

But if a proper site was found and if a design was approved, Little and Brady both balked at financing a garage.

“There’s no way on God’s green earth that this mayor can come in and pledge general obligation bonds to build a zoo garage,” Little says. “You could make a case for the Cooper-Young [garage] deal that there is business activity and yadda, yadda, yadda, But the zoo? Heck, I don’t know if you’d even get five votes [from the Memphis City Council] for that.”

The zoo raised a total of $35 million from private sources for Teton Trek and the coming Zambezi River Hippo Camp exhibits, Brady says.

“But raising money for a parking garage is almost impossible,” he says. “People don’t give dollars for parking garages. Our donors want to see what their gifts do in the community. For example, there will be 60 million to 80 million visitors in the 50-year life of the hippo [exhibit].”

The Nuclear Option

Little offered up one other solution in a conversation last week. He says it was maybe only one wrung down from a “nuclear option” and to avoid it, park advocates could be spurred toward a compromise: trams running through the Old Forest to shuttle zoo visitors from satellite parking lots.

“We’ve checked and there’s nothing that precludes it,” Little says. “Is it inconsistent with the [1989] master plan? Maybe. But there’s no prohibition to doing the trams.”

The idea was abhorrent to Buttermore. CPOP’s biggest recent victory was getting the Old Forest designated as a state natural area, which offers it special protections (against motorized vehicle traffic, among other things, Buttermore says). To them, the Old Forest is the hallowed sanctuary in the park they love, and running a tram through it would, indeed, be the nuclear option, Buttermore says.

“If the city and the zoo are upset about people going out and sitting on the grass on the weekends, people are going to throw a fit [if trams are allowed],” Buttermore says. “So many people run and walk their dogs [in the Old Forest]. The daily users of the road in the Old Forest is probably like 110 times that of the daily users of the Greensward. [The Get Off Our Lawn group] was a small group of protestors. If they ran trams through the Forest, they’d really see a protest.”

Brandon Dill

Brandon Dill

Poppy Belue, 9, stands up on her father Michael Belue for a better view as they watch Cedric Burnside Project perform during the free summer concert series at the Levitt Shell in Overton Park.

Show Me Yours?

No matter what happens at Overton Park, it’s pretty clear that all of its residents — the zoo, the park, the Memphis College of Art, The Memphis Brooks Museum — are going to be neighbors for a long time. And as those venues get more popular (as they have in the past few years) then they all need to show each other plans on where they’re headed, says Sullivan.

“I feel we need to consider how we’ll accommodate new visitors as we make improvements to the park and to the zoo as it continues to grow in popularity and it will,” Sullivan says. “We need to be looking ahead, years down the road, and making sure any improvements we make or plans that we make now are flexible enough to accommodate that future usage.”

Buttemore says it would be as easy as getting all those neighbors together and sharing master plans.

Conserving on Conservancies

The fight for the Greensward is not done, but it has impressed Little with another idea that could affect parks across the city in the future.

He says conservancies are great on the surface, and he likes the idea of private citizens rallying behind a park to make it better for everyone. But he’s afraid the structure of these public-private partnerships have maybe been too loose and given too much power to the private managers such as OPC. He’s also afraid private groups could end up cherry picking the city’s nicer parks.

“We could turn around one day and all of the prime city assets are under some kind of conservancy,” Little says. “The fact is, these [partnerships] reinforce the idea that ‘this is my park’ as opposed to something that belongs to everybody.”

Sullivan, the OPC’s director, says Little’s idea was “interesting.”

“I would absolutely say that we don’t consider ourselves owners of the park,” Sullivan says. “This is very much a city park and we manage it on behalf of the city and behalf of the citizens of Memphis. So, we’re trying to deliver what those citizens want.”

Conservancy deals are coming together now for Audubon Park in East Memphis, Little says, and also for Downtown’s Morris Park at the corner of Poplar and Manassas. Decisions on those deals, he says, will be informed by what’s been learned at Overton Park, including the fight for the Greensward.

Game of Parks, anyone?

Greg Cravens

Greg Cravens

by Regis Lawson

by Regis Lawson  by Regis Lawson

by Regis Lawson  by Regis Lawson

by Regis Lawson  by Regis Lawson

by Regis Lawson  by Regis Lawson

by Regis Lawson

by Regis Lawson

by Regis Lawson  by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks