It’s a sunny spring day in March, and biofuels activist Andrew Couch can’t stand the idea of staying indoors.

“Can we do this outside somewhere? I don’t care where, but it’s too pretty today to sit inside,” Couch tells me on the telephone as we make last-minute arrangements for an interview.

A couple of hours later, Couch pulls up to the Flyer‘s downtown office, the engine of his 2000 Volkswagen Jetta sounding loud, like a big rig. He powers it on biodiesel, a clean-burning fuel produced from renewable resources such as soybean oil, cottonseed oil, and even animal fat.

“My car gets close to 40 miles to the gallon,” Couch boasts.

I hop in and we head down to Tom Lee Park, where we spend the next hour on a park bench facing the Mississippi River, talking about Couch’s dream: a city running on alternative fuels.

Several years ago, when Couch was converting car engines to run on French-fry grease with his former company, Deep Fried Rides, it was a radical vision. These days, Couch’s idea of a bio-powered utopia is not too far from fruition.

Heading up the West Tennessee Clean Cities Coalition (WTCCC), one of three regional programs in the state devoted to taking the biofuel cause mainstream, Couch has helped connect numerous city agencies and municipalities with biodiesel producers and distributors.

Mainstream folks across the country are embracing the biofuels movement. Even President George W. Bush, in his 2007 State of the Union address, said “alternative fuels are essential to [his] goal of cutting U.S. gasoline usage by 20 percent in the next 10 years.” Bush called on the biofuels industry to produce 35 billion gallons of renewable fuels by 2017.

Here in Memphis, a couple of local biodiesel refineries are already hard at work. Memphis Biofuels in Orange Mound and Milagro Biofuels in North Memphis began production last fall.

And all across Shelby County, various municipalities and agencies, ranging from the city of Millington to Memphis Light, Gas and Water, are making the switch from straight petroleum diesel to a biodiesel blend (a mixture of pure biodiesel and petroleum).

“It’s taken a while for people to feel comfortable enough to invest [in biofuels] here, but we’re seeing the market grow around the country,” Couch says. “People are starting to feel more comfortable.”

It’s an environmentalist’s dream come true, and if the enthusiasm continues to grow, Couch says Memphis and the rest of the country can expect cleaner air down the road.

Farmed Fuel

Tucked away on a dead-end street in Orange Mound, Memphis Biofuels looks like a factory that would be more at home on Presidents Island than near a residential neighborhood. There are massive storage bins, gleaming silver tanks, pipes, vessels, boilers, and other industrial equipment.

Built in the 1920s, the facility once housed a Procter & Gamble fats-processing company. A rail line running through the plant delivered poultry fat, yellow grease, and soybean oil to be converted into poultry feed. Years later, current owner Ken Arnold took over the factory, changing the end product to cattle feed.

“In the middle part of 2005, our business at this facility was not doing very well,” Arnold says. “We were looking at better ways to utilize our facility. I have a chemical engineering background, but I was just like the general public: completely naive about biodiesel. I started looking into it and realized it was a simple process of converting soybean and methanol.”

After talking to Couch and Frazier Barnes and Associates, a local consulting firm, Arnold drew up a business plan to convert the aging facility into a state-of-the-art biodiesel plant. He hired about 40 employees, mostly from the Orange Mound area, and began production in December 2006.

Memphis Biofuels uses soybean, cottonseed, or canola oils and poultry fat or beef tallow to produce a raw biodiesel product that’s sold to oil distributors. The distributors mix the product with petroleum diesel — usually 10 or 20 percent biodiesel to 80 or 90 percent diesel — and sell it to fleets and retail service stations.

Though the finished product used in diesel engines contains some petro, the mixture results in a substantial reduction of unburned hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, and particulate-matter emissions.

“Pure biodiesel is a nonhazardous, nontoxic biodegradable fuel,” Arnold says. “It’s very similar to vegetable oil. If you have a spill, it’s not like having a diesel spill that’s very hazardous and flammable. You can even pour biodiesel on your arm or drink it.”

A jar of the thick, yellowish fluid sits on Arnold’s desk. Its color is similar to canola or low-quality olive oil.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

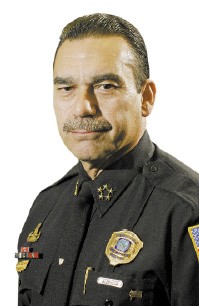

Dennis Gladney at a MATA refueling station

In 2000, biodiesel became the only alternative fuel to successfully complete Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) tests for health effects under the Clean Air Act. According to a Department of Energy study, use of 100 percent biodiesel results in a 78.8 percent reduction in carbon-dioxide emissions.

And since it comes from renewable resources rather than being extracted from below the earth like petroleum, biodiesel is credited for having a positive energy balance. For every unit of energy needed to produce a gallon of biodiesel, 3.24 units of energy are gained.

“It’s important to understand that petroleum comes from an extractive technology where resources are being pulled from a store of ancient sunlight in the ground. Then we’re emitting carbon into the air as we burn the petroleum,” Couch says. “But if we take grass [or other plants] and use that to make a fuel, that grass or that plant will grow back next year and absorb as much carbon as was released when the fuel was burned. It’s kind of a closed-loop carbon-emissions system.”

Since the raw products (mostly soybeans) used to produce biodiesel come from America’s farmland, biodiesel production benefits farmers. And of course, using less petroleum means spending less U.S. dollars on foreign oil.

Memphis Biofuels aims to produce 36 million gallons of biodiesel by the end of 2007. In 2008, they hope to boost production to 50 million gallons. But they’re not the only ones manufacturing the fuel locally. Around the same time that Arnold was trying to figure out what to do with his aging facility, Nashville native and environmentalist Diane Mulloy was pondering how she could use her time to better help the earth.

“I have three young children, and I’d stayed at home raising them. I was ready to get back to work, so I started looking at all the different industries,” Mulloy says. “A friend told me about the biofuels industry, and I just knew that was what I wanted to do. I grew up in farm country, so I have a soft spot for farmers. The petroleum prices were skyrocketing, so it seemed like a good time to give that industry some competition.”

Mulloy’s husband owns a Nashville chemical company, so he had the background needed to start a biodiesel plant. A friend, Gary Meloni, owned an old warehouse in Memphis’ newly revived Uptown district, and the Mulloys found an investor in Lehman-Roberts, a Memphis-based road contracting company.

So Milagro Biofuels, located in a converted 19th-century cotton mill on Keel Avenue, was born. “Milagro” is Spanish for “miracle,” and farmers often refer to soybeans as the “miracle crop” for its multiple uses.

Unlike Memphis Biofuels, Milagro only uses soybean oil to produce its biodiesel product — no animal fats or other types of plant-based oils.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Andrew Couch

“Soybean oil makes really good biodiesel. It does well in cold weather. Animal fat gets very thick in the winter. Biodiesel is more expensive to produce with only soybean oil, but it makes for a premium product,” Mulloy says.

“Another problem with animal fats specific to our location is the odor involved,” Meloni says. “Being in a new residential neighborhood, that’s the last thing we want.”

Seventeen new houses are planned for the neighborhood surrounding Milagro, so the company does its best to blend in. Unlike Memphis Biofuels, Milagro doesn’t look like a factory from the outside. In fact, it looks more like an office building. That’s because all the tanks and vessels are concealed indoors. Meloni says the equipment is quiet, and the only thing neighbors might smell is the hunger-inducing aroma of fried chicken.

Milagro aims to produce 5 million gallons of pure biodiesel per year, which equates to over 83,000 acres of soybeans per year.

The Ethanol Option

Though biodiesel can only be used in vehicles with diesel engines, another alternative fuel is catching on for gasoline-powered cars. Corn-based ethanol is produced mainly in the Midwest, where most of the nation’s corn is grown. It’s essentially a grain alcohol that can be mixed with regular gas at blends as high as 85 percent ethanol to 15 percent gasoline.

There’s only one operating ethanol producer in Tennessee: Tate & Lyle in Loudon County. But production is under way for a new facility in Obion County in West Tennessee. Two other companies, Mean Green Biofuels and Cascade Grain Ethanol, have received tax easements to build facilities in Memphis.

“Memphis can’t be in a better spot. You’ve got all this agriculture, the river, the infrastructure for distribution,” Couch says. “It’s a huge economic opportunity for local farmers. This is the biggest thing to happen to Tennessee farmers since the New Deal.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Memphis Biofuel’s Ken Arnold

As the owner of a farmer’s marketing service in Brinkley, Arkansas, Carl Frein helps farmers sell their crops to big food industries, like Cargill, Inc. Frein says farmers had a hard time getting a fair price for their crops several years ago, but thanks to the biofuels boom, crops are finally pulling decent prices.

“You can blame all the good prices on the corn market and the ethanol. Now we’re not only looking at a food. We’re trading an energy and a food product,” Frein says. “As long as these crude oil prices stay above $40 a barrel, ethanol is going to work for [the farmers]. These plants are going to make money, and they’re going to make more ethanol. And we’re going to need more corn to service it.”

It’s not just good for farmers. It’s also great for local air quality. Currently, Shelby County does not comply with EPA pollution standards for ozone. Much of the pollution is due to diesel emissions along Interstate 40.

Though Bob Rogers with the Shelby County Health Department says carbon emissions from diesel don’t affect the ozone layer, he admits that increased biodiesel use would definitely clear up the county’s air.

“Right now, there are no rules or regulations having to do with greenhouse gases and global warming,” Rogers says. “That may change one day. The EPA is currently studying diesel exhaust very strongly and considering calling it a hazardous pollutant.”

Biofueled Bandwagon

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Biodiesel ready for testing

When Germantown environmental commissioner Joe Skelley revs up his 1985 Mercedes, an appetizing scent comes from the tailpipe. Some days it smells like onion rings or french fries; other days it’s grilled hamburgers or deep-fried turkey.

The commissioner, who, along with 11 others, advises the Germantown Board of Alderman on environmental issues, powers his car on straight vegetable oil that he retrieves from area restaurants. He’s been running on grease in the spring and summer months for the past two years. That’s because pure vegetable oil tends to clog up in cold weather. (Biodiesel does not.)

“Since March 1st, I haven’t been to a service station, and I’ve driven 700 miles,” says Skelley, who also works as a chemist at a local drug company called Natureplex.

Skelley gets his grease at no charge from restaurants that would otherwise have to pay to have it hauled off. He also gets donations from friends and co-workers who don’t know what to do with leftover cooking grease. (Skelley handled his own vegetable-oil conversion, but local company Deep Fried Rides can do the work for those not inclined to do it themselves.)

Though it’s not as high-quality as biodiesel, Skelley’s project got the commission members talking about how they could bring a similar technology to Germantown’s fleet vehicles. They discussed a switch to biodiesel several years ago, and in March, the municipality announced they would begin testing five fleet vehicles (fire trucks, parks vehicles, and utility service trucks) on biodiesel fuel.

A biodiesel pump, containing a B10 mix (10 percent biodiesel to 90 percent diesel) provided by Milagro, was erected at the Dogwood Fire Station at 8925 Dogwood Road. If successful, all of Germantown’s fleet will be switched over, and Mayor Sharon Goldsworthy would like to eventually move vehicles up to a B20 mix.

Shelby County is also working toward a switch to biodiesel. Last May, Rogers and county clean-air coordinator Ronné Adkins announced that the county would soon begin testing fleet vehicles on biodiesel. At the time, there were no local biodiesel producers. Now that’s covered, and Adkins says he’s shooting to begin testing by the end of May — Shelby County Clean Air Month.

The county will start with a diverse group of vehicles — some off-road construction equipment, heavy-duty dump trucks, and light-duty vehicles.

“I have a feeling we’ll gradually move toward using biodiesel throughout the entire fleet,” Adkins says. “We haven’t set a date. That will depend on our fleet-services manager. When he’s ready to move forward, we’ll do so.”

If tests prove that biodiesel works as well as regular diesel in county vehicles while emitting fewer pollutants, about 100 vehicles will begin using a B20 mix.

There’ll be no testing in Millington, where the government switched its entire fleet to B10 biodiesel last month. The north Shelby County town was in need of new diesel tanks at its government fueling station earlier this year, so officials thought it was a good time for the conversion.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Joe Skelley

Biodiesel can be stored in a regular diesel tank, but it must be cleaned out first. Biodiesel acts as a solvent, loosening up diesel sludge buildup. With brand-new tanks, no cleaning was necessary for Millington.

“There’s more and more information available that shows that other fleets that have switched are running well. And they’re also seeing increases in tenths of a gallon or even a whole gallon in gas mileage on biodiesel,” says Valerie Chapman, Millington’s director of economic development. “We’re really comfortable with the role this region can play in the economy of this product. We’d be silly not to support it.”

Memphis Light, Gas and Water (MLGW) is preparing to perform biodiesel tests on its light-duty trucks, which handle gas leaks and service-outage calls.

“If all goes well, as we think it will, we’ll expand biodiesel use into our other trucks and aspects of our operation,” says MLGW spokesperson Chris Stanley.

Memphis Biofuels will provide the fuel. The utility is also planning to purchase up to 10 flex-fuel cars that can run on either gasoline or an ethanol blend.

Last summer, Memphis Area Transit Authority (MATA) performed biodiesel tests in 20 of their buses used to provide door-to-door service for people with disabilities. The results showed that B20 biodiesel produced lower exhaust emissions and increased fuel efficiency by .02 miles per gallon.

However, MATA declined to switch to biodiesel at the time due to cost concerns. The cost of biodiesel was several cents higher than diesel due to rising soybean costs. But these days, biodiesel is selling several cents cheaper. Earlier this month, officials at MATA announced that they’d switched over all 229 of their buses. At the current prices, MATA is saving four cents per gallon using biodiesel as opposed to petroleum diesel.

As for the average consumer, Memphians driving diesel-powered cars and trucks like Couch’s Jetta will soon be able to fuel up at the Riverside, a BP station on Riverside Drive in the South End neighborhood. Owner John Gary began working on installing a biodiesel pump earlier this month. It will be the first retail station to sell biodiesel in Shelby County.

“It’s no fun to be the first one at the dance, but somebody’s got to do it,” Gary says on his decision to sell biodiesel. “I’m excited and concerned that I’ll soon have lots of local competition. Once it’s been proven to work here, it’ll move quickly to other stores with diesel infrastructure.”

Green Islands and Grant Funds

If Governor Phil Bredesen has his way, Gary’s prediction is right on. In February, Bredesen announced several initiatives aimed at increasing biodiesel use and production in Tennessee.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Milagro Biofuel’s Gary Meloni (left) and plant manager Paul Sammons

One of which is the Biofuel Green Island Corridor Grant Project, a $1.5 million grant program to assist retail fueling stations along I-40 in converting and installing fuel storage tanks for biodiesel and ethanol. The Governor’s Alternative Fuels Working Group stopped taking applications for the project in mid-April.

“We hope to have a string of ‘green islands’ across the interstate system. That way a person with an alt-fuels vehicle could go no more than 100 miles on the interstate and find a station with E85 or B20 for sale,” says task-force member Joe Gaines, who also serves as assistant commissioner for the Tennessee Department of Agriculture.

Bredesen is awarding $4 million in grant funds to local farmers looking to get their products in the alt-fuels marketplace.

“Currently, much of the oil being used is coming from out-of-state sources,” says Gaines. “We’re offering funds to build a soybean-crushing facility that would buy soybeans directly from farmers, crush them in the state, and then sell the oil to a biodiesel-production facility.”

There’s also $1 million in state funds set aside for counties, municipalities, and public-education institutions looking to purchase alt-fuels for fleet vehicles. And the governor is launching an education campaign to help the average citizen better understand the benefits of using biodiesel and ethanol.

The 2007 Governors Conference on Biofuels, a convention for anyone interested in learning more about alt-fuels, is set for May 31st at Montgomery Bell State Park in Burns, Tennessee.

But the state isn’t just talking the talk. Tennessee operates 60,000 flex-fuel vehicles that can run on either ethanol or gasoline. The Tennessee Department of Transportation (TDOT) converted their East Tennessee fleet to biodiesel back in 2005. TDOT’s Middle Tennessee transition is under way now, and the West Tennessee switch is expected by the end of the year. By 2008, all of the yellow TDOT HELP trucks along I-40 will be biodiesel-powered.

The government has proposed $70 million for prototype research into the future fuels from other sources. Some in the alt-fuels community fear soybeans and corn will eventually run out.

“There are limitations on the amount of corn and soybeans that can be produced in the state and nation and still maintain food production and all the other requirements we have,” Gaines says. “We’re very rich in the Southeastern U.S. in grasses and trees and other lignin-type materials. That’s where the big growth is seen five to 10 years out.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

No matter what sources are used down the road, much work is being put into mapping out a future for fuel sources besides petroleum and gasoline. If the country hopes to meet Bush’s goal of 35 billion gallons of renewable fuels by 2017, the industry has nowhere to go but up. And the environment can do nothing but benefit.

Back on the bench facing the Mississippi River, Couch ponders the future of biofuels. Where does he see the industry in 10 to 15 years?

“Big and consolidated. Efficient and cleaner. Accomplishing more than just fuels. The bio-refinery model will take biomass and turn it into all kinds of different products,” Couch says. “What we’re seeing now is a stepping stone. We’re working our way to a more efficient and sustainable future.”

But it’s going to take more than switching to biofuels or producing bio-based products.

“If we don’t start curbing our energy use,” Couch says, “it’s not going to matter what we do. It won’t be enough.”

He squints as he points toward the bright sun hovering over the Mississippi River. “Right there, that’s all the energy in the world. That’s all we have.”

For updates on which West Tennessee retail stations will be providing biodiesel or ethanol in the future, go to www.wtccc.com.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Susan Lowe

Susan Lowe