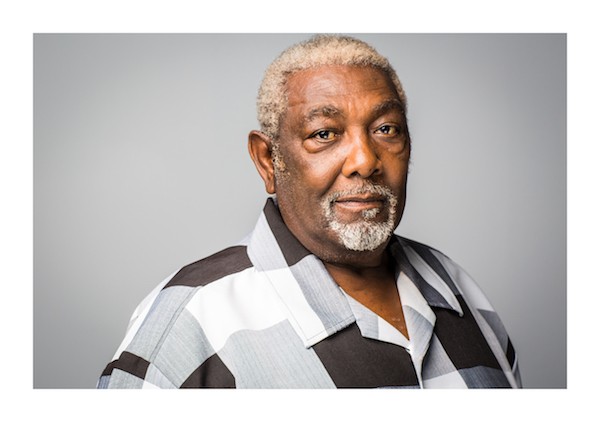

Larry Kuzniewski

Larry Kuzniewski

Everybody poops. Just ask my 8-month-old daughter. Or the Grizzlies when they shat the bed in a 111-83 loss at the Pacers to start the season. It’s a part of life. Poop is smelly and gross, but it can also be funny and heartwarming. Need proof?

In a battle of the dads, Marc narrowly beats Mike in the diaper-changing speed competition. pic.twitter.com/Kwy2LQbZXO

— Matt Preston (@flyergrizblog) October 20, 2018

Grizzlies Maul Hawks 131 – 117

As far as Grizzlies gamebreak entertainment goes, this one is immediately in my top ten. The premise is perfect for Conley and Gasol, both fathers with young children. The video says so much about them, even though the two men barely utter a word. You see them as humans and fathers. You see their personalities. You see how they’re able to have a conversation without words.

Conley and Gasol scored 11 and 13 points, respectively, with heavy minutes in the season-opening blowout loss against the Indianapolis Pacers. The Grizzlies’ overall team offense looked flat and dysfunctional. Nobody could break down the Pacers’ defense. Grizzlies fans were quick to hit the panic button on Twitter, with some calling Gasol washed up.

That foul mood changed Friday night, when Conley and Gasol revived their high-level two-man play, proving they can still be the engine of a successful team. Conley sped all over the court, breaking down defenders off the dribble, swishing two threes, and setting up his teammates with 11 assists. Gasol didn’t appear to be limited by the back spasms he experienced earlier that morning, running the floor normally and whipping crisp passes to his teammates to the tune of 5 assists.

Larry Kuzniewski

Larry Kuzniewski

Although they didn’t lead the way in scoring, Conley and Gasol’s two-man game set the table for the rest of the team. The Grizzlies would hope to see this pattern repeated throughout the regular season, as Conley and Gasol are aging veterans with lots of mileage, and they should conserve their energy and health as much as they’re able before the Grizzlies are (hopefully) wrestling for playoff seeding.

Larry Kuzniewski

Larry Kuzniewski

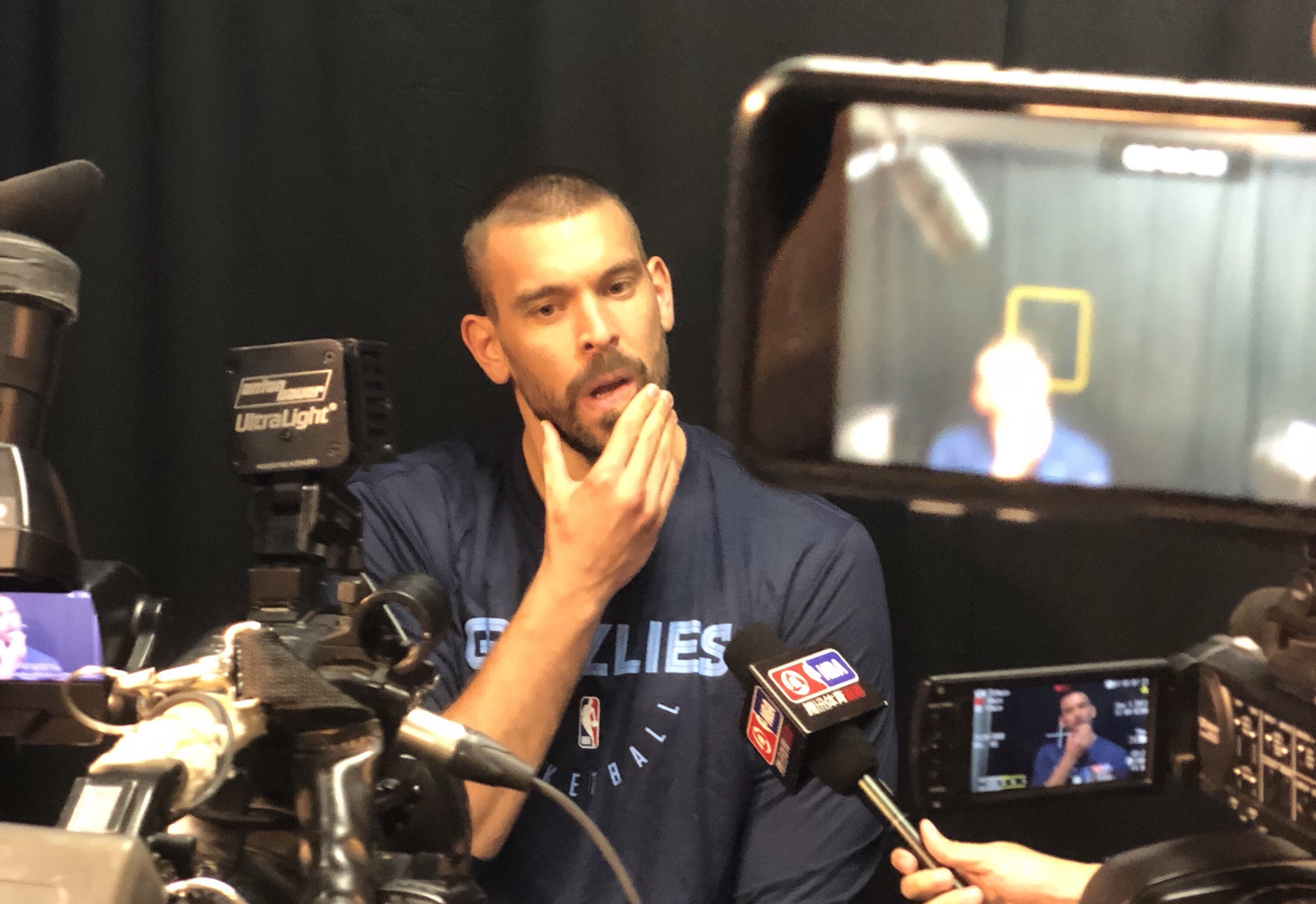

In his first regular season game with the Grizzlies at FedExForum, Garrett Temple quickly caught fire, and that blaze raged for the rest of the night. He lit up the Grindhouse with 30 points on 10-11 shooting, and was nearly flawless from deep, hitting 5-6. He also defended and handled the ball well.

Garrett Temple has 30 points on 10-11 shooting, 5-6 from three. pic.twitter.com/11lg8emqV1

— Matt Preston (@flyergrizblog) October 20, 2018

Grizzlies Maul Hawks 131 – 117 (2)

Was he 100 percent happy with his performance? In the locker room after the game, Temple said “I was actually real upset at myself for giving up that three to Taurean Prince — the first three he got.” When asked about Temple in his postgame presser, Coach J.B. Bickerstaff was quick to laud his defense, saying that there will be some nights where Temple won’t hit as many shots, but he’ll lock down the opponent’s best player.

Garrett Temple is good because he’s a guy you don’t have to teach how to fit into your system. He reads the guys around him, positions himself accordingly, and just takes the opportunities he gets. Also, he can handle better than people give him credit for. He showed that at LSU.

— Andrew Ford (@AndrewFord22) October 20, 2018

Grizzlies Maul Hawks 131 – 117 (3)

Larry Kuzniewski

Larry Kuzniewski

How did the Grizzlies’ top draft pick do in his first home game of his first NBA season? Let’s just say he’s doing a pretty good job at endearing himself to the fanbase.

i would take a bullet for Jaren Jackson Jr

— Chip Williams (@chipwilliamsjr) October 20, 2018

Grizzlies Maul Hawks 131 – 117 (4)

Triple-J poured in 24 points off the bench, shooting 8-12 and going 2-4 from deep. His length and quickness transformed the defense. His shooting and defensive impact come as no surprise. What does surprise me, however, is how good he looks in the post and attacking the paint. Consistently, he was able to use his size, strength, and athleticism to work his way into the paint and finished over defenders like 7’1″ Alex Len. His touch around the rim has been impressive.

Jaren went from not being able to finish layups around the rim to pushing nba 7 footers around and finishing left hand hooks better than Zbo in like 2 weeks

— ㅤflemdawg1hunna (@Flemdawg1Hunna) October 20, 2018

Grizzlies Maul Hawks 131 – 117 (5)

Rookie Jaren Jackson Jr. scores 24 PTS for the @memgrizz at home! #NBARooks #GrindCity #KiaTipOff18 pic.twitter.com/35lvDrBxep

— NBA (@NBA) October 20, 2018

Grizzlies Maul Hawks 131 – 117 (7)

Chandler Parsons got the start over Kyle Anderson, but played fewer minutes than Anderson. Parsons shot 3-6 from deep and contributed 11 points in the game. One sequence stood out to me in particular: Conley beep-beeped through the defense and jumped beneath the rim, and slung a pass to Gasol at the top of the arc. Gasol immediately swung the ball to a wide-open Parsons for a made triple. It was a rare glimpse at the power of what the three highest-paid Grizzlies can do to a defense when they’re healthy and in sync.

I wrote about this in-depth for the Flyer‘s cover story this week, but the Grizzlies basically haven’t seen and don’t know the capabilities of a healthy version of this team. I’m betting that those unknowns play out as unexpected positives. Did you know that the Grizzlies set a franchise record last night by scoring 77 points in the first half?

Larry Kuzniewski

Larry Kuzniewski

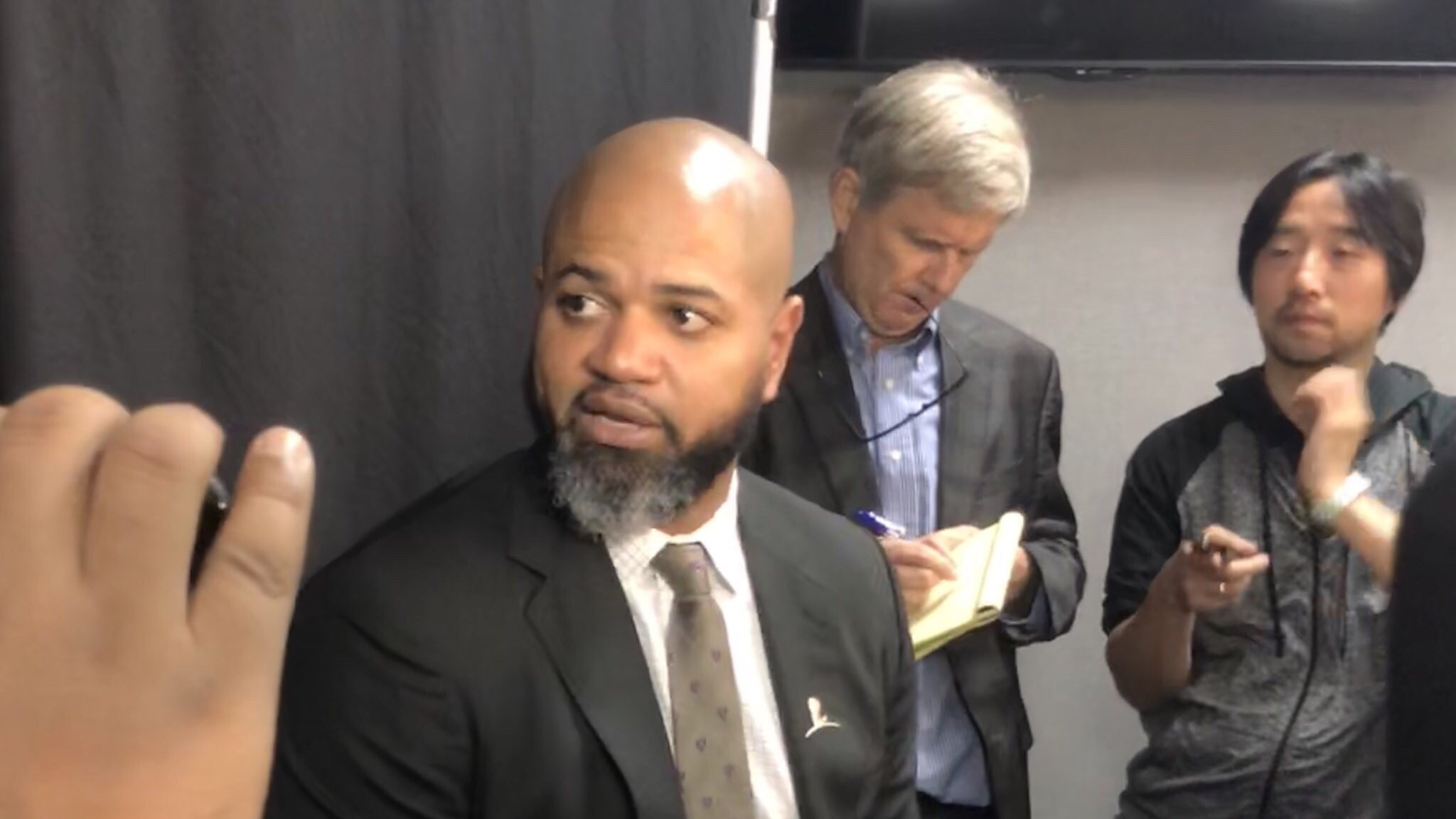

The one down note from the home-opening win was JaMychal Green’s injury. He broke his jaw colliding with a player’s elbow while contesting a fast break dunk attempt. He hit the ground, pounded the court with his hand, hopped up, and ran straight to the locker room. He underwent a “surgical stabilization procedure” this morning.

J.B. Bickerstaff said the injury shows how selfless Green is — that he was the only one contesting a difficult play. And how tough do you have to be to leap up off the floor and jog to the locker room with a broken jaw?

Dillon Brooks saw limited minutes, logging just two in the first half, but got more run in the second. Even though he was (conspicuously, for Grizzlies fans) on the bench for most of the first half, Brooks was highly engaged, celebrating when Shelvin Mack hit a buzzer-beating floater, and jumping up and cheering harder than anyone else when Jackson slammed home a lob.

Andrew Harrison didn’t play at all in the home opener. And unlike Brooks, he seems disengaged, seclusive, and dissatisfied sitting on the bench. I don’t know how much to read into that, though, since their personalities are so different and perhaps that’s just how Harrison is in general. In any case, people forget how good Andrew Harrison was at the end of last season, and he’s by far the best defender among Grizzlies point guards. I hope Memphis manages to work him into the rotation again, because he brings a lot to the table when he’s playing well.

The Grizzlies de-escalated an anxious fanbase on Friday. They’ll look to build some momentum when they take on one of the West’s scariest teams, the Utah Jazz, on Monday on the road.

Burn of the night:

plumlee looks like he won a contest from a mountain dew bottle cap and the prize was you get to play in an nba game

— thiccen loans arena (@LilHannahS) October 20, 2018

Grizzlies Maul Hawks 131 – 117 (6)

Matt Preston

Matt Preston  Matt Preston

Matt Preston

Matt Preston

Matt Preston  Matt Preston

Matt Preston  Matt Preston

Matt Preston  Matt Preston

Matt Preston

Khz | Dreamstime.com

Khz | Dreamstime.com

Darius B. Williams for Striking Voices

Darius B. Williams for Striking Voices  Darius B. Williams for Striking Voices

Darius B. Williams for Striking Voices