Kurt Pershke, RedBall Project in Paris

Kurt Pershke, RedBall Project in Paris

The RedBall in Paris

The Brooks Museum of Art announced this week that as a part of its centennial celebration, it is bringing artist Kurt Perschke’s “RedBall Project” to Memphis. The “RedBall Project” is a temporary and site-specific installation piece that involves the placement of a giant, inflatable red ball at various significant points around town. The locations where the Ball will be placed are determined by Perschke, who spends time biking, walking and otherwise exploring the city in the months before the Ball is placed.

The Ball’s placement in other cities has looked loosely to be the work of some toddler-like deity: balanced at the edge of bridges, inflated in doorways, shoved beneath underpasses. It’s funny and unsettling without being too unsettling. It says, “Hello, this is an international city where inexplicable art stuff happens.” It’s the kind of thing Memphians will remember years out: “Ah yes,” we’ll murmur to our cyborg grandchildren, “2016… the year that we were visited by the Ball.” Here are some pictures of the “RedBall” in other cities, so you can get the idea.

In short: the Ball will be fun. The Ball will be different. The Ball should (but will probably not be) placed directly on top of the statue of Nathan Bedford Forrest, like a bloated clown nose. The Ball will introduce temporary and site-specific art to Memphis, and it will do it with cosmopolitan style. We are good with the Ball. But will the Ball be a veiled comment on mass surveillance? Let’s discuss.

A hypothetical situation: It’s a sunny midsummer day in Memphis. You’re walking down the street, drinking an iced latte, when you notice that your favorite intersection has been visited by a massive red ball. You stop drinking your latte, mid-sip. You feel suddenly more aware of yourself, of your puny human size, of how zoned-out and unquestioning you were moments before. The RedBall has seized your attention, changed your relationship to the corner and how your body feels as you approach the corner.

You move closer. The RedBall stays in its position. Maybe you put a hand out and feel its rubbery redness. But you can’t move it. It’s really heavy. So you circumnavigate. Your latte-infused commute has been effectively changed, forever. Meanwhile, the Ball is mute, unchanging, super-bright in its super-occupation of public space.

This is a weird experience, huh? Or maybe it is not so weird, because it triggers something in your brain. It triggers the memory of the other thing that was recently installed on your favorite corner: that blinking, blue camera box that provides the Memphis Police Department with 360-degree surveillance of your block. Operation Blue CRUSH, as the camera boxes are called, also made you check yourself in public space. The camera established a ball-shaped zone of spherical surveillance that, while invisible, is very much palpable.

Before you come at me with accusations like, “Oh, what, are chemtrails real too?”, ask yourself: What is the point in a big, red, ball? Our public art could conceivably be anything. It need not be static or silent. It need not be immobile or durable. It could ask things of us. It could tell a story. But a red ball does none of those things. A red ball is just a silent presence — an elephant in the proverbial “room” of the commons.

Is the “RedBall” a comment on the normalization of mass surveillance? Probably not. But will the way we meet it be more normal because Memphians are used to large and inexplicable presences in our neighborhoods?? It’s possible. Whether or not it is intended (and, let’s be real, it’s not), the fact is that in its red and spherical reticence, the Ball is like surveillance: whether or not it watches us is beside the point. The point is that it makes us watch ourselves more closely. Now excuse me while I go get a latte.

Facebook

Facebook

Kurt Pershke, RedBall Project in Paris

Kurt Pershke, RedBall Project in Paris

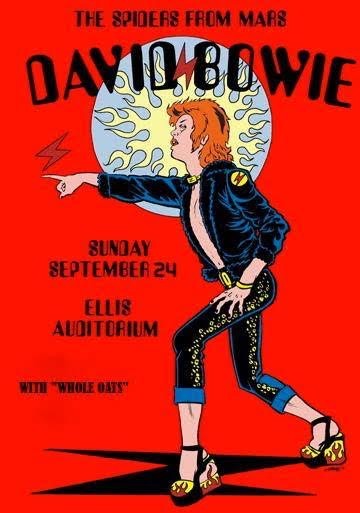

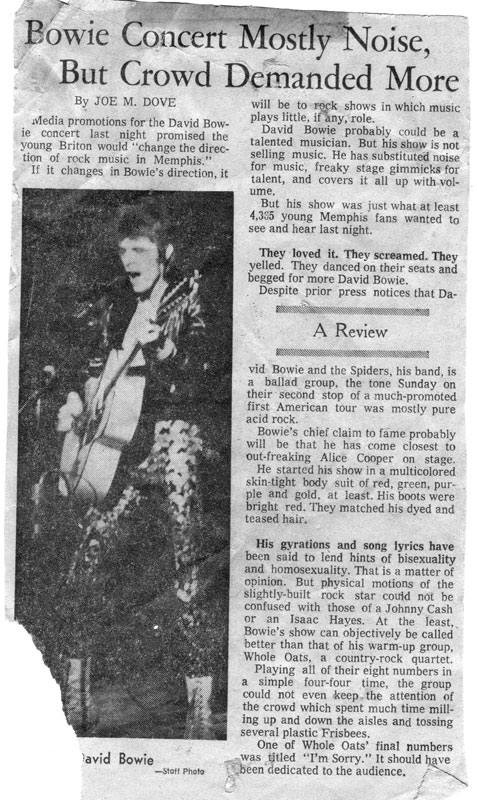

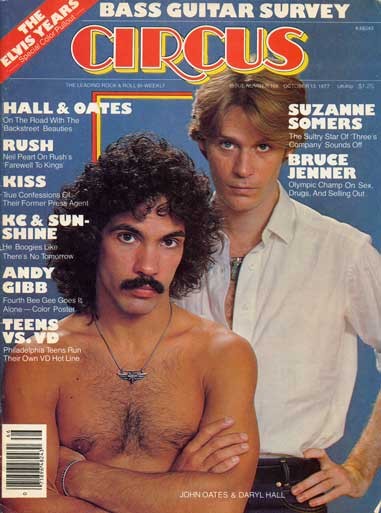

Ladies and gentlemen, Whole Oats!

Ladies and gentlemen, Whole Oats!