“You’re a pawnshop, Huddy. You’re supposed to be in a bad area.”

That’s Joe Marr, Huddy Marr’s successful builder/developer brother who lives in Germantown, doing the talking. Joe owns the building housing Huddy’s business, Bluff City Pawn.

“Pawnshop should be close to bad,” Huddy, who’s just trying to make a honest living, answers back. “Right on the edge of bad. Just a little ahead of bad.”

And that’s right where Bluff City Pawn is: out on Lamar, pretty close to bad. But the stores on either side of Bluff City are closing shop. A blood bank’s moving in. Bluff City’s about to get real close to bad. And that’s why Huddy Marr is looking to move the business, and he has his eye on Liberty — Liberty Pawn, on Summer.

“You must be the only person who drives down Summer and says, ‘Count me in,’” Joe later says to his brother. “Summer and Lamar, they’re both ghetto streets.”

“Summer is doing business with the whole city,” Huddy, who knows his stuff, says in response. “Don’t matter ghetto.”

[jump]

And maybe, business-wise, it doesn’t matter. What matters more in the new novel Bluff City Pawn (Bloomsbury) is family. And family starts to really matter when Huddy, Joe, and a younger brother named Harlan, back from Florida with nothing to his name (apart from a police record), enter into a deal.

Nothing fishy about that deal, nothing un-law-abiding about it. Huddy has been offered to buy a valuable gun collection off a rich widow in Germantown. Huddy, Joe, and Harlan stand to earn real money off the resale of those guns. But Huddy knows that it’s critical they do the deal right. He knows how ATF operates. More than ATF, he knows how his brothers operate. Which is why Huddy puts it this way going in: “As long as we don’t trust each other equally, we’re okay.”

Until, after the deal’s done, they don’t trust each other equally. That’s when things in Bluff City Pawn go south. And no, this is not Memphis overlooking the Mighty Mississippi. It isn’t Memphis, home of the blues, birthplace of rock-and-roll. Beale Street might as well be a world away. This is Memphis as tourists don’t see it but as citizens day to day live it. It’s Memphians staying put despite the city’s leadership and hardships. It’s Memphians pulling up stakes to seek greener, safer pastures out east. It’s Memphis as only an insider could depict it. Except that this novel’s author, Stephen Schottenfeld, is no native son. He grew up in Westchester County, just north of New York City, and he got his MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

But before moving to the University of Rochester, where Schottenfeld now teaches, he was on the faculty at Rhodes College, and during his years there, 2003-2008, he got to know this town real well. He wrote a short story called “Stonewall and Jackson,” which appeared in New England Review in 2006. He wrote a novella set in Leahy’s Trailer Park called “Summer Avenue,” which appeared in The Gettysburg Review in 2010. For Bluff City Pawn, though, Schottenfeld knew he needed a wider field — a story with more possibilities, more points of tension.

So Schottenfeld got to know local pawnbrokers, local builders, local realtors, and even local garden-club members. He visited local gun shops, gun dealers, and gun shows. He talked to local ATF agents on the right way to write up a gun inventory, on how those agents conduct themselves. And Schottenfeld wanted especially, as he said in a phone interview from his home in Rochester, to thank all those good people who helped him in his research: “They were incredibly generous with their time.”

Schottenfeld’s literary agent, once he read the manuscript of Bluff City Pawn, was something else: puzzled.

“He expected, first of all, a Southern accent,” Schottenfeld said. “Then his next question was: ‘Did you grow up around a pawnshop or a lot of guns?’ I said: ‘No, I didn’t … at all.’”

What Schottenfeld did grow up blessed with is a fine ear for dialogue (he once worked in film postproduction in New York; he’s taught screenwriting in his classrooms), and Bluff City Pawn confirms it: No over-obvious Southernisms here; just the plain-spoken (verging on elliptical) give and take you’d expect to hear between a business owner and his customers (or brother to brother) and the more polished strains (and no less elliptical speech patterns) you’d be likely to hear among Germantown’s old-guard, horsey set.

Schottenfeld also has a real eye, not only on the broad canvas but down to the smallest, most telling matters. You want a tutorial in the right way to handle a pawnshop customer angling to sell a non-flat-screen TV? It’s here in Bluff City Pawn. The right way to lay out the merchandise so you’re not, when your back’s briefly turned, robbed blind? That’s here too. So too the smoothest way to earn the trust of a gracious widow and to skirt the superciliousness of her superannuated preppy son.

Call details such as these “texture.” Schottenfeld does, and it’s the product of this author’s almost journalistic attention to real-world verismo:

“I’m curious about people’s lives. I don’t have a great storehouse of autobiographical tales. I don’t tend to reach back into my own childhood. There is a journalistic impulse in me to get out there, do the fieldwork. And yet I’m not interested so much in nonfiction. As a writer, I’m interested in ‘texture,’ specificity of language, information. I’m interested in what people do. I want to observe it, understand it. And Memphis, at the time I wrote this book, was kind of perfect for me.

“Before I moved to Memphis, I didn’t think of myself as a writer of ‘place.’ But my eyes and ears were opened when I was there. I was so interested in what people were saying, what people were doing around me. But when I realized I was going to be writing about pawnshops, yes, it was intimidating. I knew there couldn’t be any shortcuts. I was going to have to ‘negotiate’ this new space … write as a real insider. William Faulkner, Alice Munro, Daniel Woodrell: They’re steeped in place. They gain their authority through their years in those cities and towns they write of. But there are other writers who gain their understanding of place precisely because they’re not from it.”

But forget Memphis for a moment. Consider its big suburb to the east.

“Germantown was for me the ‘discovery’ of the book. I’d lived inside the city, in Memphis. I’d had my own feelings about Germantown. And, frankly, it didn’t interest me much. But I came back to Memphis a couple more times and came to, in some ways, appreciate the impulse to flee, like my character Joe. Some reviewers have talked about him as the villain of the book, and he may act in a villainous way. But I’m moved by his work ethic, how honest he’s been in so many ways. He just got caught up in a bad time.”

The bad time Schottenfeld is referring to is the recession of 2008, which threatens to ruin everything Joe’s worked so hard to achieve, and that includes a big house and garden and an upscale enclave of unsold houses he’s built in a development called Heritage Cove.

But what of Harlan, one part lost little boy, two parts real rascal?

“I’m sad for him,” Schottenfeld admitted. “He’s an unintimidated kind of guy. But what scares him are these memories he can’t reconcile — memories of his family when he was growing up: what wasn’t there for him; what wasn’t given to him.”

And as for Huddy Marr — Bluff City Pawn’s wonderfully drawn major character: Can’t question his street smarts and realistic view of the way the world runs. But can you also think of Huddy in terms about as un-Southern as can be: Samuel Beckett and Franz Kafka? Schottenfeld can:

“I may write in a social-realist vein. My work may be located in an actual place and not some blasted non-zone. But, like in Beckett, there are ways that Bluff City Pawn ‘gestures’ at feelings of being lost, of being estranged, of being caught in some zone where you’re not regarded, you’re not understood. And as in Kafka, there are moments in the book where Huddy is caught by forces — institutional forces, bureaucratic forces — inside a system that even he, at times, can’t decipher.”

Which brings us back to Beckett and his minimalist mode. Surprising to think, but there’s that too in Bluff City Pawn, which is as naturalistically told as any novel by Richard Ford or Russell Banks. Still …

“There’s something about a pawnshop that has a kind of elemental connection to what a story should be and can do,” Schottenfeld said.

“You’ve got two characters. You’ve got a counter separating them. Things are being pulled out, placed on the counter, individual pieces. I’m looking at that counter, those little bits.” •

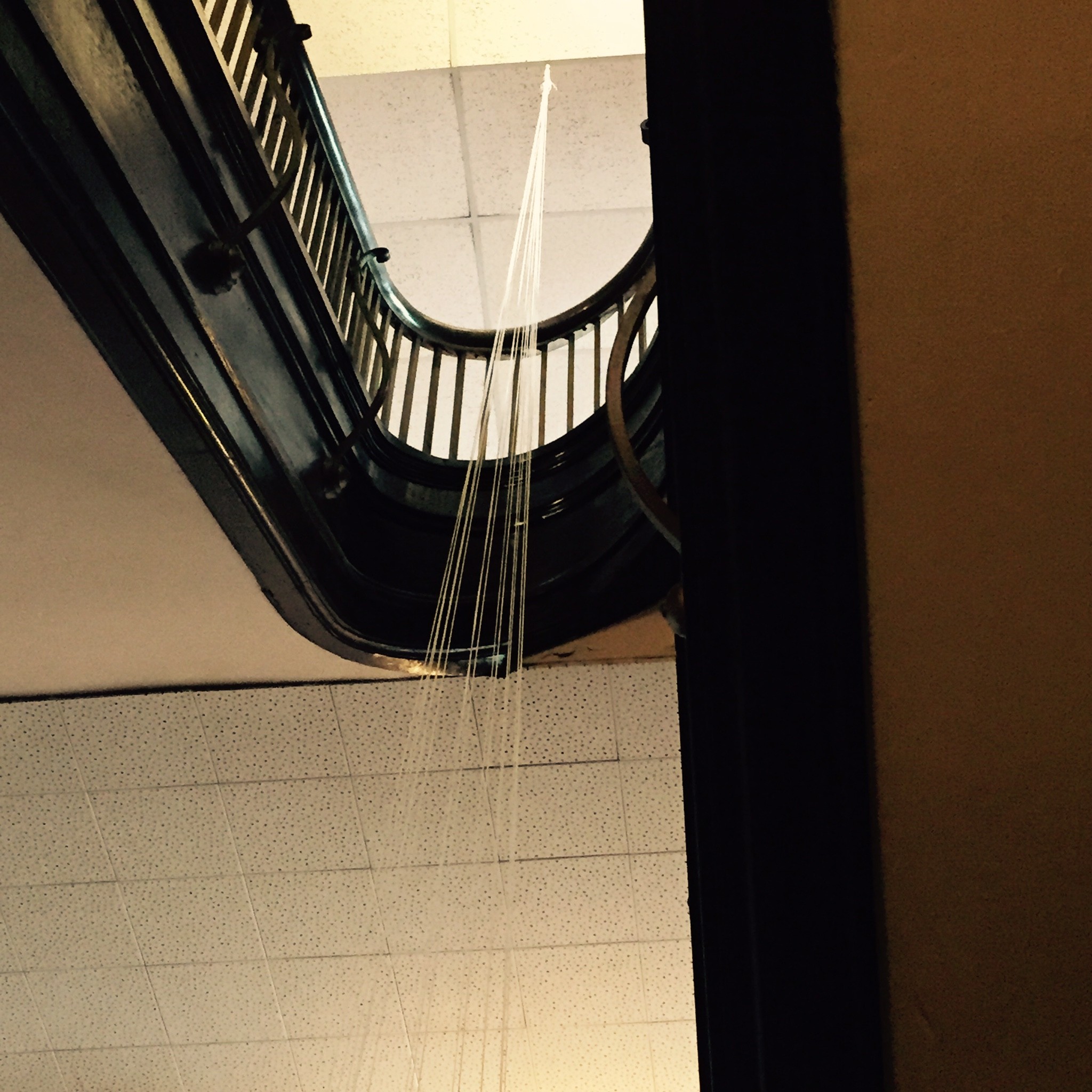

Stephen Schottenfeld will be guest of the River City Writers Series at the University of Memphis on Tuesday, September 16th, when he will read from and sign Bluff City Pawn. The reading is inside the University Center’s Bluff Room (Room 304) and begins at 8 p.m. A student interview with Schottenfeld will take place the next morning in Patterson Hall, Room 448, at 10:30 a.m. For more on the River City Writers Series, go here.

Rogues Gallery

Rogues Gallery

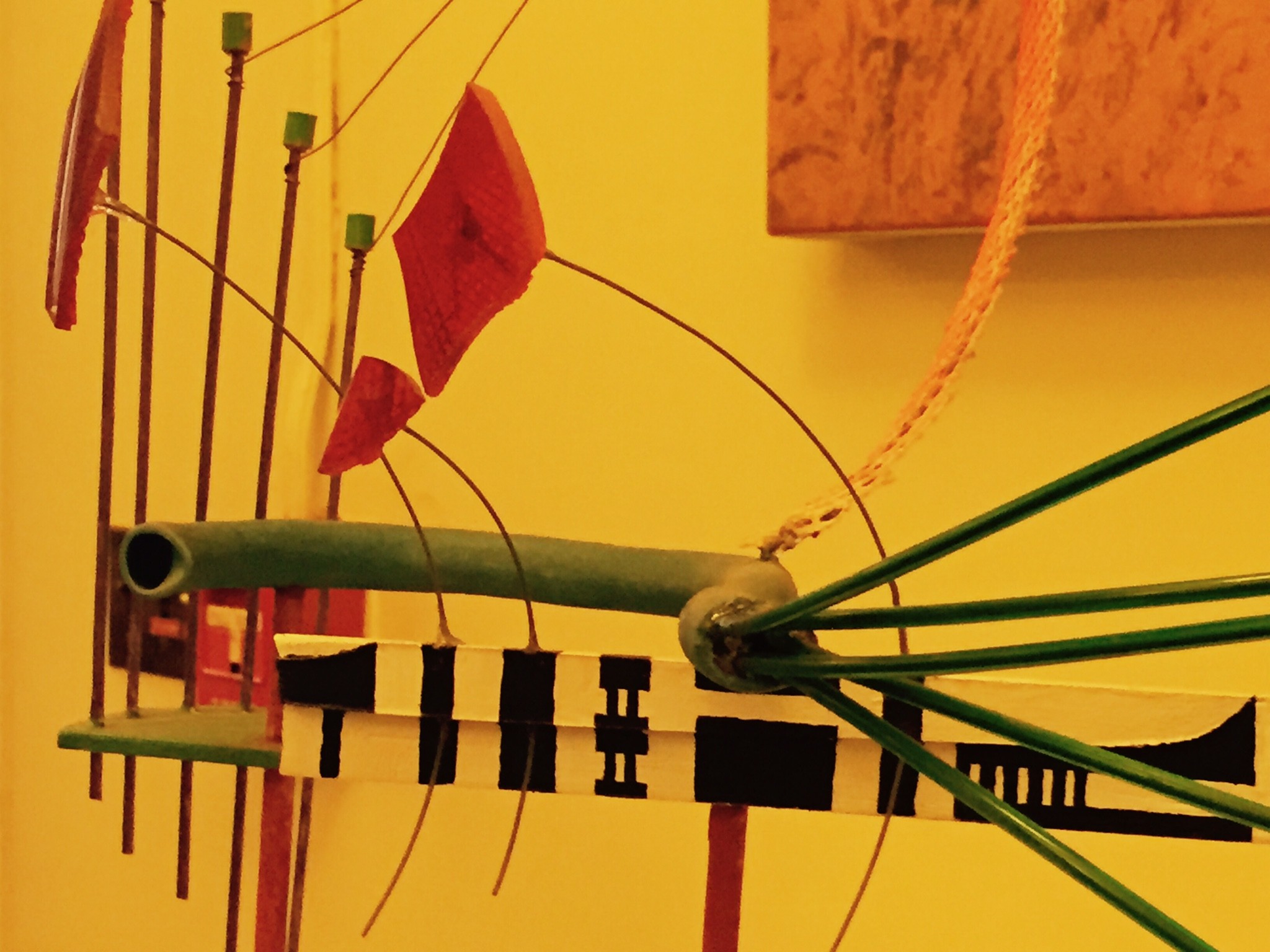

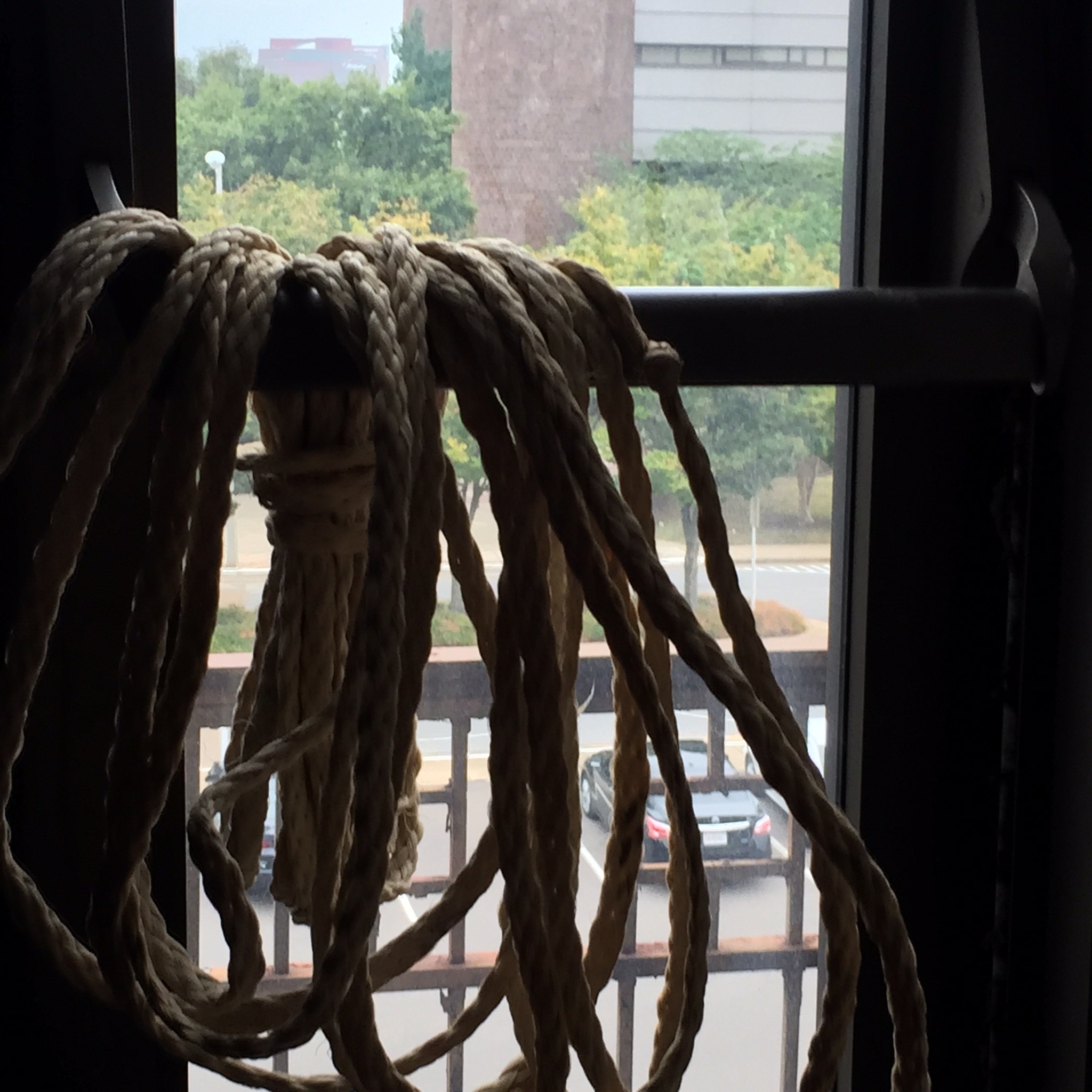

Sculpture by Roy Tamboli

Sculpture by Roy Tamboli

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

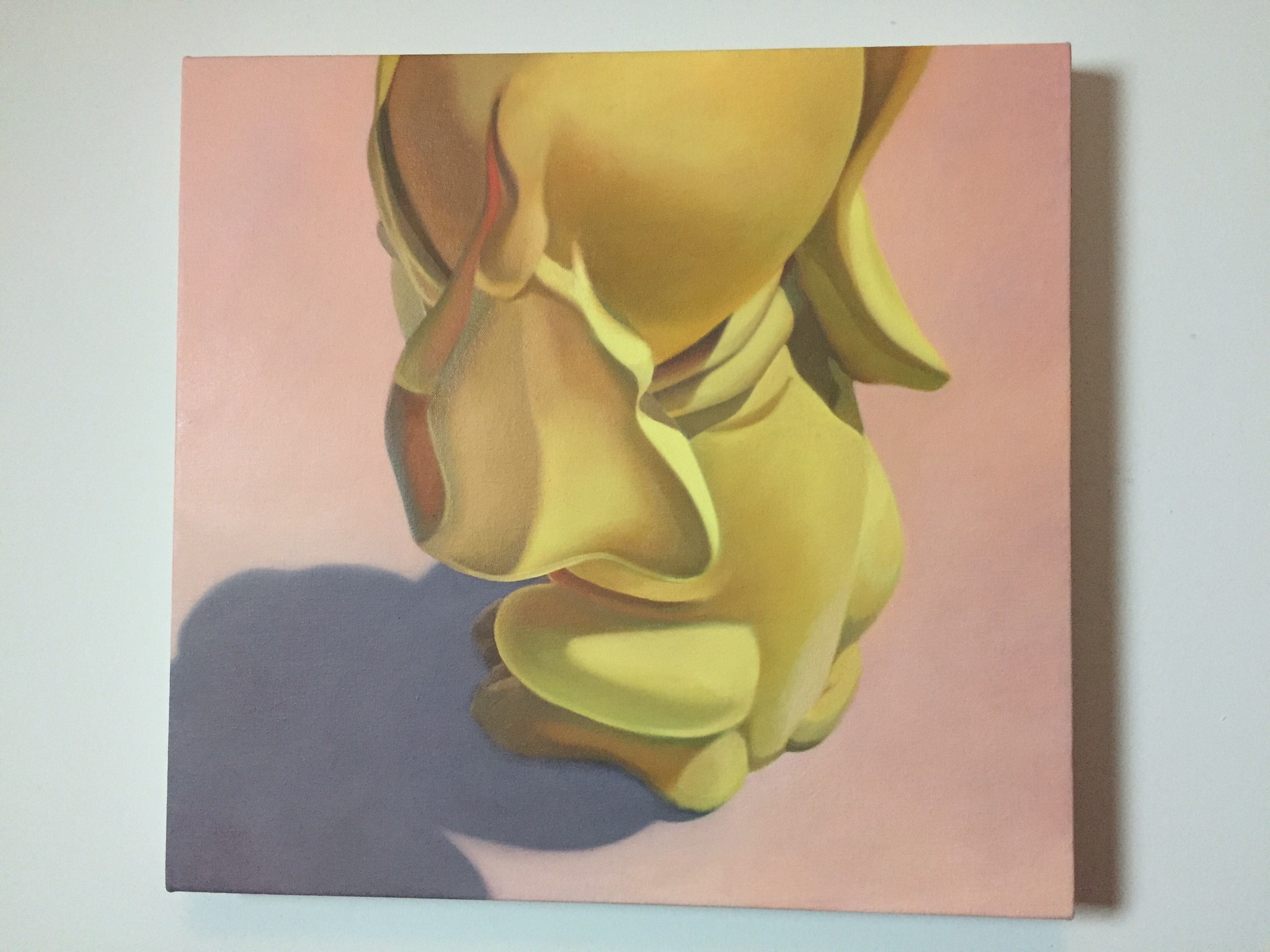

Aviana Monasterio

Aviana Monasterio  Head and the Heart

Head and the Heart

Josh Miller

Josh Miller  Josh Miller

Josh Miller

Jamie Harmon

Jamie Harmon