I was going to write something sad and ranty in this space, something to the effect of arg! everything is terrible — because, frankly, it feels that way. But I don’t need to detail at length all the horrific stuff going on in the world or how the dollar no longer means much and we’re being bled dry just to eat, put gas in our cars, and have roofs over our heads. I’ll spare you the talk about how our essential workers are — still, and maybe even more than ever — overworked and underpaid, and how our bodies and livelihoods will soon be (more) at the mercy of politicians and corporations while the rich get richer and the rest of us scrape by and hope that we can access affordable healthcare and homes and have the freedom to choose what’s best for ourselves. Things just feel a little … precarious. But we won’t talk about that.

I recently went to visit family down South in my hometown of Greenwood, Mississippi. My pawpaw Clark was set to have surgery the following week, and such procedures are trickier on the elderly. I’d hoped to watch Dirty Dancing — the original with Patrick Swayze, of course — with my granny Clark (it’s our favorite movie), but she wasn’t feeling up to it. We instead spent time chatting and catching up. Things are much quieter there, simpler, slowed-down. Not that crime and drugs and inflation and rising rent and home prices haven’t touched the small community. The place isn’t what you’d call idyllic, to be sure, but there’s a big difference between meandering through a country town inhabited by fewer than 14,000 people and traversing the daily grind in a sometimes rough, always-on city like Memphis.

I spent a couple nights with my dad and brother while I was there. My brother is a wheelchair-bound 32-year-old with severe cerebral palsy. My dad takes care of him — baths, diapers, feeding, outings, entertaining and supporting in the best ways he can. Their address is on one of the “county roads” on the outskirts of town. My dad built (literally) the house he lives in, on my pawpaw’s land. It’s not your typical house. To me, it always looked like maybe it was supposed to have been a big garage or shop at first, but became an actual living space with a kitchen and bathroom and bedrooms. It has concrete floors and is filled with antiques and road finds — a real hodgepodge — and the yard looks a bit like Sanford & Son Salvage. My dad can’t work much these days since he cares for my brother with only a few hours of outside help from the “sitters” (they’re nurses).

One afternoon, my dad and I climbed into a beat-up ATV, and he drove us over to a nearby creek. I held onto the “oh shit” bar while he zoomed up the gravel road and down the side of a little-too-vertical (for me) levee. Unafraid, that man. No reservations. In his already muddy boots, he walked right through the water, in places up to his knees, as I, unprepared, maneuvered the muck in my city shoes. We talked about the state of things, how I sometimes have trouble navigating days, especially since the pandemic basically dismantled everything we thought we knew. In the wake of all that was flipped upside down, some of the pieces no longer fit. Whatever normal was, it isn’t that anymore. So many things seem … broken. He talked about prayer and gratitude, and I said I might give the former a try.

There’s peace to be found there somewhere. Not specifically in that creek or the Delta town itself, but in that state of mind. Live gently and simply and without fear, love the life you have, give thanks.

I know I said I wasn’t going to write something sad in this space, but I’m known to be overly sentimental. My pawpaw ended up canceling his aneurysm surgery. He’s not one to slow down much and has decided, it seems, he’d rather go on his own terms — while feeding his dog out at the hunting camp or hamming it up with folks at the grocery store — than risk losing his life or mobility on a surgeon’s table. In the weeks since our visit, my granny received a tragic diagnosis — cancer in her lungs and liver — and was put on hospice. It doesn’t look like we’ll get in another viewing of Dirty Dancing. But I’m grateful for the many times we watched it together, and for all the precious memories with my Clark grandparents; for my brother and dad and what they’ve taught me through positivity, perseverance, and the wisdom that only comes from living in the present, not clouded by material wants or looking too far beyond the scope of what we can control.

Just faith, hope, and love.

Source: US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Source: US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Jeanne Seagle

Jeanne Seagle

Pink Palace Museum

Pink Palace Museum

Facebook/Rhodes College

Facebook/Rhodes College

SCS

SCS  ACES Awareness Foundation

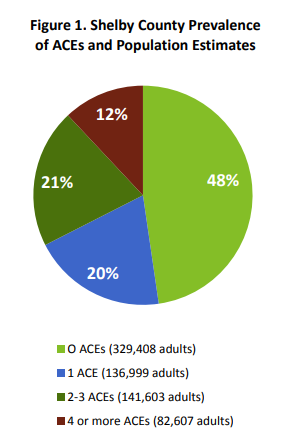

ACES Awareness Foundation