We get some choice comments here at The Memphis Flyer.

Last week, we featured Memphis Black Restaurant Week in The Memphis Flyer weekly Food News column, and naturally, one intrepid newsletter reader raised a thematic question: “Really? Only way I celebrate this is if next week is Red Restaurant Week and the next Purple Restaurant Week etc……….[sic]. C’mon people, let it go.”

If this reader’s lamentation strikes a chord with you, you might ought to skip over the next couple of pages. Likewise, if there’s a purple-hued restaurateur out there in Memphis, please email me, because I want that story.

This story is about up-and-coming Black artists in Memphis. And when we say Black artists, we mean we are drawing attention to three of them — an itty-bitty, teeny-tiny microscopic slice of the landscape of Black creativity that pulses throughout the 324 square miles comprising Memphis. And while interviewing these three young artists, we asked them what other Black artists they think we should keep our eyes on. It’s the right thing to do — you go to the experts who are thriving and creating while juggling an existence designated as political merely because of their melanin.

This isn’t the first Memphis media attempt to showcase talent springing from a demographic that makes up 63 percent of our city, and it certainly won’t be the last. But the history of ignoring African-American voices and achievements runs deep in this country, and Memphis is no exception. It’s not enough to build museums dedicated to Black progress and call it a day.

One issue isn’t going to neutralize generations of silence and neglect. It’s up to Memphians of all demographics and socioeconomic standing to invest in and explore the arts, businesses, restaurants, and enterprises of Black Memphians. Because for the majority of people in our city, much of history equates to erasure, and the antidote to erasure is celebration.

Ziggy Mack

Ziggy Mack

Ziggy Mack

Ziggy Mack: On the Zoom

“I’m probably not going to sleep tonight, but that’s okay.”

That’s Ziggy Mack, a native Memphian, who is currently splitting his focus between this interview and booking a flight to Atlanta, with a continuation on to Cape Town, South Africa.

If you’re around Mack for more than five minutes, you might wonder if he ever sleeps at all. Words rat-a-tat-tat out of his mouth at a machine-gun pace.

“I learned the trick to avoiding jet lag,” he explains, excitedly: “If you just try to match the time zone you’re headed to, you won’t get jet lag. If you go to sleep in your own time zone, then you’ll have jet lag.

Mack calls it “guerilla traveling,” and it’s a skill he’s sharpened over the last few years as his career in photography has commanded a fair amount of globe trotting — Scotland, Ireland, and Peru, to name a few destinations.

For this particular journey, Mack is headed to a workshop that will enhance his already specialized talent in underwater ballet photography.

But before there were submerged arabesques, Mack got his start in sweaty nightclubs as a night-life photographer, commissioned to capture sweaty Memphians gyrating away, possibly fueled by Red Bulls and vodka. Mack’s employers were impressed with what he was able to capture in dimly lit clubs amid the throes of nightlife chaos.

Ziggy Mack

Ziggy Mack

Photography from his ‘Underwater Ballet’ series.

“They kind of … saw something in me,” Mack says with a shrug. “So they gave me an opportunity and camera equipment, and I just started with that.”

Clubs birthed his photography career, but it was when Mack was applying to grad school in Chicago in 2012 that he was forced to up the ante.

“I was trying to get into law school, and I needed a crazy gimmick. So I thought, ‘Well, people love ballet,’ even though I didn’t particularly love ballet. But hey, I’ll get good at it,” said Mack.

Mack not only got good at ballet photography, he fell in love with ballet. The element of water was added later as an homage to a past relationship.

“I was definitely drowning in love,” said Mack, throwing in another shrug.

Though Mack’s marriage of ballet and underwater photography has served him well, like so many other artists in Memphis, finding his bearings in a notoriously competitive field was challenging.

But what does it mean to be a Black artist on the move in a town hampered by inequality and lack of access. Was it any different?

“This is kinda tricky, right?” Mack said. “In terms of accessibility, I would give it a two or a three. But, the thing is — it forces you to work harder. It forces you to be better than where you currently are.”

Mack acknowledges that there’s always an underlying thought that artists wanting to carve a career should leave Memphis, especially Black artists. Mack notes that he’s heard from Black artists of all mediums who’ve left, and they relay to him a sense of total shock.

“They’ll tell me, ‘Man, people are hiring me for the absolute bare minimum.’ I’m used to working so, so hard,” said Mack.

For Mack, his second break came through his friendship with Memphis-based photographer Joey Miller. “If he wasn’t there to introduce me and say, ‘Hey, he’s a good person, his work is great’, I could very well be doing the exact same thing as when I started.”

Mack knows that, while he is talented, he was also fortunate to have the connections that helped propel him forward. He also knows not every Black artist in Memphis has those connections.

“It’s not even a glass ceiling; it’s a glass wall,” said Mack. “You can see through it, you can make a lateral move, but you can’t go through. It’s crazy.”

Andrea Gutierrez

Andrea Gutierrez

Kevin Brooks

Kevin Brooks: Just Keep Filming

When Kevin Brooks was about 6 years old, he watched The Matrix.

Seventeen years later, as I’m trying to forget how old I was when The Matrix came out, Brooks is perched on a chair in a coffee shop explaining how that movie sparked his interest in film.

When talking about The Matrix, Brooks gets excited all over again, as though he just watched Keanu don the trademark black Neo sunglasses for the first time.

“It was visually inspiring, but at the same time, it had so many philosophical messages. Of course, I didn’t understand those right away, when I was 6, but over time I did,” said the Memphis filmmaker. “To this day, those are the types of films I want to make.”

Brooks’ short film, Keep Pushing, is both visually enticing and has a hidden moral. While shots of soaring skateboards slice through the frame, the story’s protagonist embarks on his new-found love for skating, only to learn that he initially, well, kinda sucks.

[pullquote-1]

“The message is persistence through adversity,” noted Brooks. If this sounds like a common theme in storytelling, that’s because it is. But there was wizardry in the delivery, and executives at the Sundance Film Festival took notice.

Keep Pushing was selected as one of five films out of 300 internationally submitted for Sundance Ignite, a program created for up-and-coming filmmakers.

Since the short film’s premiere, Sundance has kept in touch with Brooks, inviting him back this year to work behind the camera, interviewing hip-hop artist Common and actor/writer Jenny Slate. Brooks also interviewed Tim Robbins and his son, Jack, who released his own movie at Sundance.

Brooks just graduated in December from the University of Memphis with a degree in film, and if the pace of his career is overwhelming to him, he doesn’t show it.

Following the release of Keep Pushing, his short film, Marcus, was a top 10 finalist for the Memphis Film Prize. His next short film, Myles, produced by Memphis filmmaker Morgan Jon Fox, will be released in April. He’s currently working on a full-length feature film, the details of which are very much under wraps.

When I asked Brooks about how he sees Memphis as an environment for Black artists, his positivity was immediate and genuine.

“I think it’s definitely getting better,” he said, as he started to tick off names of Black artists producing work that he admires.

“Pay attention to Lawrence Matthews, aka Don Lifted, a 24-year-old musician and aspiring filmmaker,” he said. “Watch for Bertram Williams on stage at Hatiloo Theatre. Listen for Jas Watson’s spoken word. They’re making a difference.”

Brooks’ prescription for bettering Memphis for Black artists syncs up with his personal philosophy: Just keep producing at all costs, and don’t be deterred by what the person next to you is doing.

“Look, we can now shoot movies on 4K on our iPhones, and that’s just one example,” said Brooks. “Whatever you have to do, just tell your story. Showcase the human condition. That’s what I try to do, and I feel like that’s the responsibility we all have as Black artists.”

Angie Nicole

Angie Nicole

Siphne Sylve

Siphne Sylve: Art Is in the Structure

Think back for a minute to high-school biology, if you were fortunate/ cursed enough to take it. The basic function of every cell in our body is to take in nutrients and raw materials and, through a series of complicated reactions, produce life-sustaining energy and respiration.

I’m convinced that somewhere in Siphne Sylve’s cellular makeup, there’s a unique structure that takes in, oh, I don’t know, smog or something equally grimy and synthesizes it into pure, raw talent.

“I want to be sure that anything I do as an artist continues to ignite new paths of thought and it continues to ignite the idea of upliftment,” Sylve said.

When she’s not managing a project through her position at UrbanArts Commission, the New Orleans native paints, DJs, crafts spoken-word poems, beatboxes, and busies herself with her next visual art installation.

As I read off her lists of talents to her, I jokingly asked, “Is that it?” Sylve laughed and said, “Um, I’m not a dancer? I don’t claim that in any type of way.”

But she does do nearly everything else, and that much was obvious to the UAC when they snatched her up in 2013. But managing projects there was not enough for Sylve. And though her own art is relatively hard to find, save for her murals along portions of the Greenline, Sylve said that this will soon change.

[pullquote-2]

“Right now, I’m in the process of creating a stronger portfolio and just really taking time to make more visual art.”

There’s a traceable theme to Sylve’s body of work: the intricacies of design. “I love the structure of things,” Sylve said. “I like to know how things are made, how things are built. That’s the bulk of my work. And whether it’s a freelance piece or something I’m making for myself, I have to know the history of something, even if I don’t use it in the work itself.”

This love of structure bleeds into the music Sylve creates as well. She thinks back to Friday nights at home as a kid, pointer finger hovering over the boombox, waiting to catch the missing track for her latest masterpiece cassette mix. Then as now, it’s all about the structure.

So, when it came time to ask her the question that I asked all artists for this story — namely how they saw Memphis as an environment for Black artists — I prepared myself for a multi-pronged answer focused through the lens of someone obsessed with the structure and history of everything in her world. I was not disappointed.

“I feel like identity for artists is an ongoing thing, especially for female Black artists. The history when it comes to artists of color, especially female artists of color, as it relates to exposure. … Well, I didn’t learn about Black female artists making art until I was about 18.”

At 18, Sylve was enrolled as a freshman at Memphis College of Art. There weren’t exactly chapters in textbooks dedicated to Black female artists. Their visibility wasn’t apparent.

“Everything I learned about [Black female artists], I either learned from my peers or I learned on my own,” recalled Sylve.

Sylve does feel like there is something happening between Black artists in Memphis, Black visual artists in particular. Something unifying. Acknowledging the local and national history where Black voices have been seldom heard (Yes, I’m looking at you Purple Restaurant Week hopeful), Sylve feels a growing sense of hope. It may take two or three years, but Sylve does sense a shift on the horizon.

“While there is a lot of unity happening,” Sylve said, “the coverage is scarce.” She said that she typically find outs about Black artists almost exclusively through word of mouth. She added, “I do think that the support is growing. The awareness is growing as well. The hope is to not let our experiences go overlooked.

“I think that sets Memphis apart from the larger context of Black artists in America. And through this unity and awareness that’s occurring, I think we have a whole new generation that’s willing to take this work and move forward.”

Let’s hope Memphis is smart enough to take notice.

Artists speak: Who You Should Watch For

Ziggy recommends:

Kenneth Wayne Alexander II

Graphic Design, Illustrator

Kevin recommends:

Lawrence Matthews, aka Don Lifted

Musician, Visual Artist

Jas Watson

Poet, Artist

Bertram Williams

Actor

Siphne recommends:

Allyson Truly

Actor, Poet, Filmmaker

Brittney Bullock

Maker, Designer

Catherine Patton

Poet

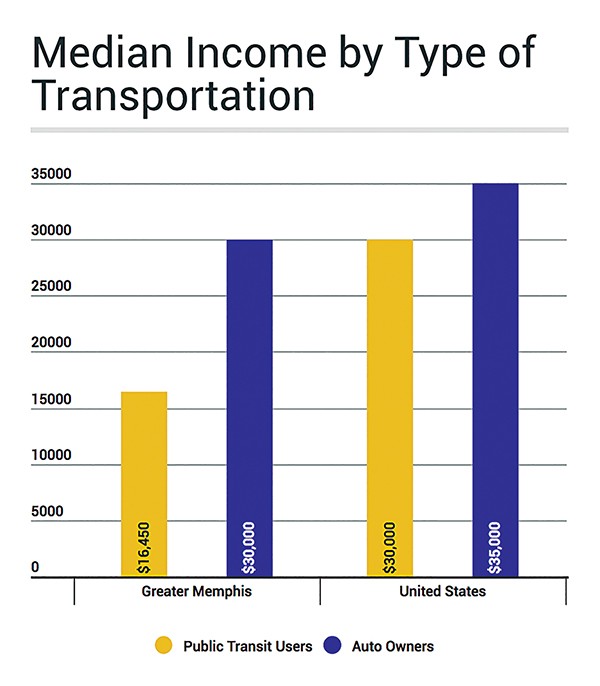

Elena Delavega, PhD, University of Memphis Department of Social Work. Research published August 15, 2014.

Elena Delavega, PhD, University of Memphis Department of Social Work. Research published August 15, 2014.