With the ideology of white supremacy on the ascendant under the current president’s reign, the activism that blossomed after a police officer killed Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri three years ago is more relevant than ever. And Whose Streets?, the new film by directors Sabaah Folayan and Damon Davis, traces the events of Ferguson from the activists’ point of view. It lends a sense of hope to a story built on tragedy and deadly frustration.

Activist Brittany Ferrell marches in Whose Streets?

Be prepared for a very different documentary experience, as this film forgoes many of the tropes of the nonfiction genre. There is no narration, only a few brief title cards that set the time and place, or frame the events with powerful quotes by the likes of Maya Angelou or Langston Hughes. The bulk of the footage is built from live phone videos. The opening scene intercuts the earliest cell footage of action on the streets with tweets posted at the same time by eyewitnesses.

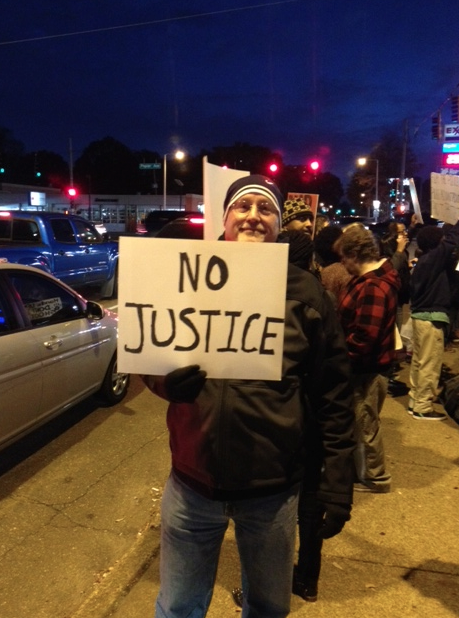

Presenting the events from street level footage, without benefit of an all-knowing narrator, immerses you in the shock and chaos of the moment. You see the immediate rage from neighbors and Brown’s family, as tweets broadcast the details of an unarmed teen shot down and left in the street for hours before being retrieved by a police SUV. And you see the immediate reaction by the police force, brandishing machine guns and a massive show of force from the very beginning. Most importantly, you see Michael Brown’s community at a personal level, not merely as a mob. This immediately sets Whose Streets? apart from most of the media footage we’ve seen again and again.

The humanization of those touched by Brown’s killing is carried throughout the film. Further footage recorded from the streets as police shoot huge rubber bullets or tear gas into crowds, or even at people standing in their own yards, is broken up by portraits of activists’ family life. Brittany Ferrell, a young student drawn into activism by Brown’s death, is seen teaching her daughter about social justice, then accepting a marriage proposal from her wife-to-be. David Whitt, a Copwatch videographer, is seen with his family as well. Such scenes of family love and support not only bring home the anguish of Brown’s mother lamenting her dead son, but underscore the community interdependence that make the activists’ work possible.

As the demonstrations surge, go quiet, and then surge again in response to new developments, one gets a sense of the deep investment these protesters have made in their fight for justice. This may be the most humanizing quality of all: the long term commitment of these families and friends is perhaps the most powerful counter-narrative to the “chanting mob” images disseminated in the mass media at the time. We hear the testimony of a white driver who tried to run down several protesters, claiming she was terrified of their “tribal chants”; but after having hearing these people speak articulately on camera, we see that testimony for the hyperbole it is.

The dignity and soulfulness of the activists is evoked with a moody score by Samora Pinderhughes. One can only hope that the soundtrack is released in its own right. I recently heard Pinderhughes lead a jazz quartet through the music at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation in St. Louis, and it revealed the power and depth of the music when allowed to breathe. It is only used fleetingly in the film, perhaps because it could easily overpower the images.

All told, this documentary is not to be taken lightly. It is grim, but as political protest becomes a near-daily requirement in the face of a race-bating, corporate-coddling administration, the message of resilience and support among these community activists can inspire us all keep our eyes on the prize.

Whose Streets?

Louis Goggans

Louis Goggans

St. Louis Public Radio

St. Louis Public Radio  Louis Goggans

Louis Goggans