An under-recognized aspect of the punk and garage scene in Memphis is the musicians’ love of strange, old records. After all, one of the best models for kicking back against corporate rock hegemony is hearing how artists made music when rock and other genres were considered the radical fringe. Such was the context back in the ’90s, when the heathen underground played venues like the Antenna and Barristers. By day, many of those club denizens were fanning out to the city’s thrift stores, combing through vinyl.

The Royal Pendletons were mainstays of the local scene then, often making the trip north from their home base in New Orleans to play with such local pioneers as Impala or the Oblivians. It’s no accident that all of the players in those bands — notably Michael Hurtt and Matt Uhlman of the Royal Pendletons, Scott Bomar of Impala, and Greg Cartwright and Eric Friedl of the Oblivians — are respected DJs and curators of rare vinyl to this day. The gigs of the ’90s often gave way to all-night record parties. Incredibly, seeds were planted then for a phoenix-like revival of the most galvanizing gospel music ever recorded in Memphis, nearly 30 years later.

A Friend You Haven’t Met Yet

Michael Hurtt recalls those days vividly. “It was during our real reign of Memphis popularity, if you will, that I found the first single,” he says. “Matt Uhlman and I were coming to Memphis even before the Pendletons. … We were always looking for records. That was a big part of the attraction. There were countless fascinating labels in Memphis that I was discovering, every time I came to town.

“As I did that, I’d find a couple things on a small label and think, ‘Wow, this is really interesting.’ Then you find more and start wondering, ‘What’s the story behind it?’ They become these living, breathing entities in your mind. It’s almost like a friend who you haven’t met yet. They’re certainly not just objects. Records aren’t inanimate. There’s a whole story there in the grooves. That’s what happened with D-Vine Spirituals.”

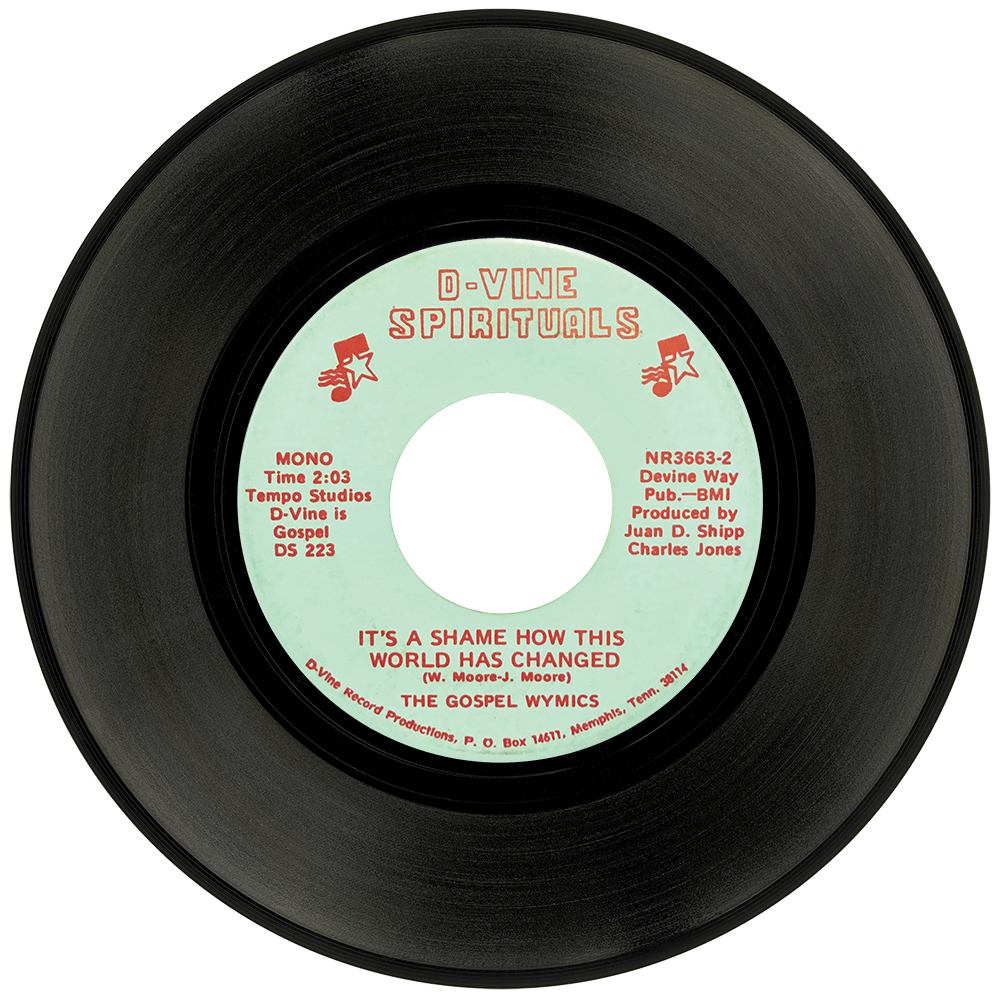

For a music devotee fascinated with the history and many expressions of the groove, gospel was a natural interest. “To me, it was just another genre that I loved and had to know about. Since I was always fascinated by Memphis music and so taken by the city and its culture, I was always buying gospel records alongside every other country and garage and rock-and-roll record. So when I first saw that D-Vine Spirituals hand-drawn logo, I thought, ‘What is this?’ It’s got so much mystique to it.”

Of course, beyond the look and feel of the old records, there was the music itself. “The whole catalog is so good and so interesting,” Hurtt says. Hearing the impassioned singing, the raw beats, and silky harmonies, he felt he’d stumbled on a vein of gold running through the thrift and record shops of the city. “I kept finding more of the records. And I thought, ‘Jesus, this label’s amazing!’”

The Punk Meets the Godfather

Sometime around 2007, after accumulating many of the D-Vine Spirituals releases over a decade, Hurtt, by then living in Detroit, resolved to dig deeper. “At one point, I noticed the name, ‘Produced by Juan D. Shipp.’ And I remember thinking, ‘This is not a very common name. If this guy is still around, I bet I can find him.’”Michael Hurtt with D-Vine Spirituals founder Pastor Juan Shipp

Pastor Juan D. Shipp recalls their first encounter well. “When Mike first called, I was a little skeptical. Who is this guy calling me?” he says. Still, he agreed to meet for coffee, and the two quickly warmed to each other. “We talked for a while, and he told me he came across a D-Vine record and he loved the sound. The sound was what caught Mike’s attention.” Shipp, who had founded and run D-Vine Spirituals from 1972 to 1987, still prided himself on the quality of the records he’d made decades earlier.

Hurtt, for his part, wasted no time. “We met at CK’s Coffee Shop,” he recalls, “and I sat down with him and a tape recorder. I wanted to get the story. That’s what I always do. From my own madness. Firstly, you do this because you just have to know. And then, of course, if you’re a writer and you want other people to know about this, you’re already thinking, ‘How can I put this in a book? Or in liner notes? A magazine article?’ The important thing is to get the story, before you even have a plan.

“So then, Juan started telling me the story,” Hurtt continues, “and he told me from the beginning, within the first minute, about Clyde Leoppard.” With that, another piece of the puzzle clicked into place. If the key to the records’ magic was their sound, that sound’s origins could be traced back to a studio Leoppard started in the ’60s, where all the D-Vine Spirituals tracks were cut.

“I already knew who Clyde Leoppard was,” reflects Hurtt. “Because I was already a Sun Records fanatic, and Clyde’s band, the Snearly Ranch Boys, backed up a lot of Sun artists: Hayden Thompson, Jack Earls, Barbara Pittman, Warren Smith, you name it. So that really struck me. Because, number one, here’s a guy I’ve always been interested in; number two, he’s a hillbilly musician. Which made total sense to me, that Black gospel and country music would have this alignment. Even if it’s just that it’s the guy’s studio. The fact is, Clyde had always wanted to record Black gospel groups, and that was part of how it all started. He loved that music. So that deepened the story. It was a watershed moment because it also showed me how Memphis the story was. In a sense, I feel like Clyde and Pastor Shipp, their journey together, their partnership, is Memphis. That is the real and true spirit of Memphis, Tennessee. An older white hillbilly musician working with a younger Black preacher to make this incredible, uniting music.”

Pure Black Vinyl

Ultimately, the true beginning of D-Vine Spirituals was prompted by Shipp’s quest for a solid sound, and Leoppard’s Tempo Recording Studio fit the bill. Not surprisingly, it all started with a conversation among DJs. In the mid ’60s, a few years after he’d started preaching, Juan Shipp also became a gospel disc jockey at radio station KWAM. The Black jockeys in town were a close-knit bunch. “I was talking with Eugene Walton, who was also with KWAM, and [Theo] ‘Bless My Bones’ Wade and Ford Nelson, who were with WDIA. We all worked together as a unit, even though we were at different stations. And I told them, ‘The sound that most groups are getting here in Memphis isn’t that good. It’s just a shame. Somebody needs to do something!’ And Wade said, ‘Well, Juan, you need to find a studio that will give them a good sound.’”

And thus Shipp began his quest for better recordings. “At that time, Style Wooten’s Designer label had a monopoly on the gospel groups here in Memphis,” he remembers. “All the records that came out of Style’s studio sounded like the guy was singing down in a well or something. I didn’t like that. So I finally found a studio, and that was Clyde Leoppard. Clyde had made an echo chamber over the top of his stairway, and oh, that had a good sound! I also heard how [acoustically] dead the studio was, and I loved that.”

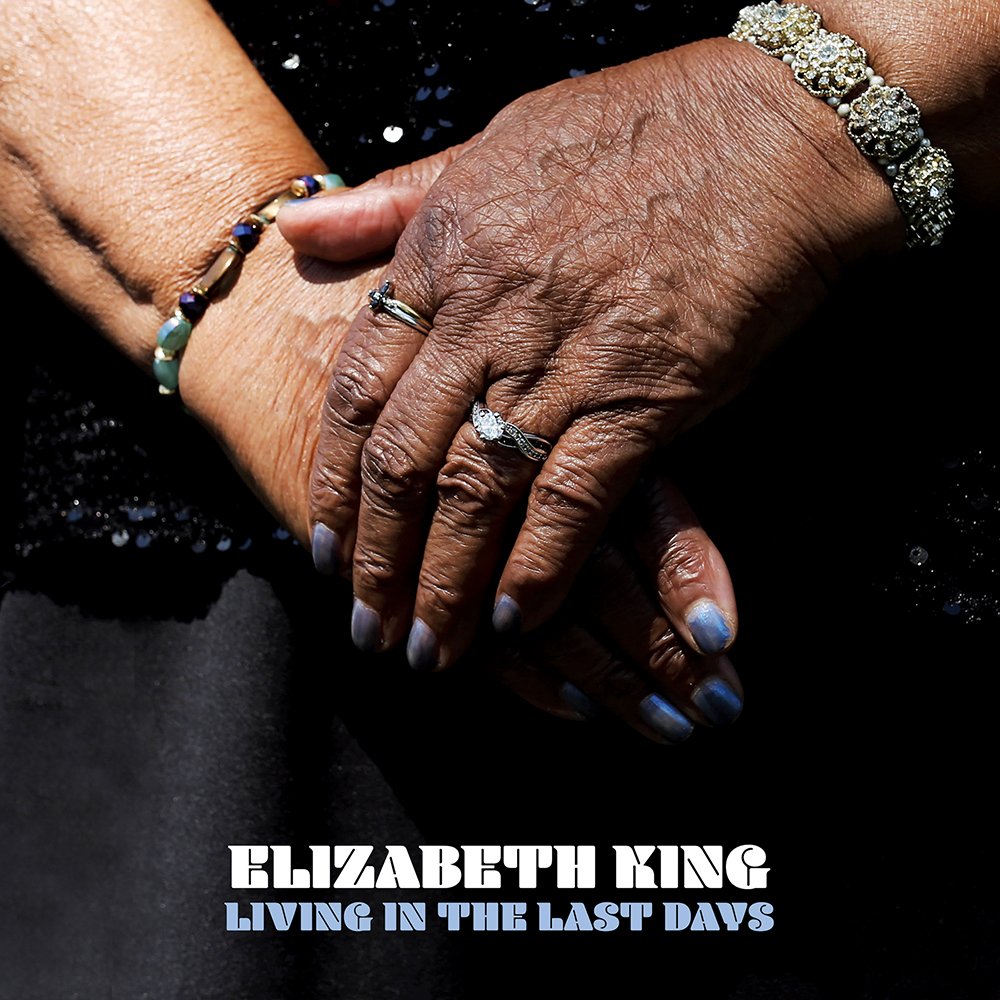

Beyond the spaces for recording, Leoppard also knew the ins and outs of making records. “I had noticed that the local labels had brownish-looking vinyl, while the records from Motown and Stax were dark black. I found out that Style was using reprocessed stuff, getting it as cheap as he could. So I asked Clyde, ‘Where do you get your records pressed?’ He worked with a place called Precision, and they used pure vinyl. I said, ‘That’s what I want.’ Because I’m Black. I can’t come out with no cheap stuff. Other folks can do that and get away with it. I said, ‘I’ve got to have pure black.’ So when I did my first records with Elizabeth King & the Gospel Souls, I sent it through Precision. And the sound was fantastic.”

Not only was the pressing pristine, the care taken to capture the label’s first group on tape paid off with a haunting recording. Singer Elizabeth King’s talent is a force of nature, and she’d already recorded tracks for Designer before connecting with Shipp. But during that first session in 1971, the D-Vine Spirituals producer took full advantage of the intimate vocals made possible in the hushed walls of Tempo to craft something unique. Abandoning the shouted delivery of so much gospel, he exhorted King to sing as if she was “making love to the Lord.” Her gripping performance still sounds immediate and fresh today. Not surprisingly, the record sold well and helped put D-Vine Spirituals on the map.

From there, the label only grew in popularity, pulling in talent from far beyond the Mid-South and garnering widespread airplay, though Shipp says that it never really made a profit. “It’s hard to make money, especially in gospel,” he says. “I got the joy out of just doing something good for the groups. That was my reward. I’d say my legacy was that I always would try to get the best out of an individual. The Lord blessed me to be able to see it there, and it was my job to get it out. Sometimes I’d even make a group cry because I’d push them so hard. Sometimes you had to use the spiritual aspect to get it out. Let them realize who they are and who they’re singing for. They’re not singing for people, they’re singing for God. If you’re singing for him, then you’ll give him your best. And if you do that, people are going to like it. Because what comes from the heart, reaches the heart.”

“Let’s Go Get Those Tapes”

Hearing such details for the first time over coffee, some 15 years ago, Hurtt was in awe and more determined than ever to take things further. As Shipp points out, “Not only is Mike a collector, he’s a fantastic writer. He wrote a book [Mind Over Matter: The Myths and Mysteries of Detroit’s Fortune Records, written with Billy Miller], and that book is this thick! He ought to be ashamed of himself.” The Pastor lets out an appreciative chuckle: In the case of D-Vine Spirituals, Hurtt’s dogged pursuit of the story led to much more than a book.

Hurtt describes how things quickly accelerated. “At one point, I asked him where the label’s master tapes were, and he said, ‘Oh yeah, they’re safe in Clyde’s studio.’ I knew Clyde had passed away, but his family had them. It was only a few months later that I came back to Memphis and said, ‘Let’s go get those tapes.’ Juan called Clyde’s niece and she said, ‘Yeah, come on out.’”

In retrospect, it seems providential that the two acted when they did. “All the tapes were in this shed, the old studio [that Leoppard had built after Tempo], which was going back to nature. The roof was caving in and there was all this water damage. They said, ‘You guys got here just in time. Our house is about to be foreclosed on.’ If we had waited two more weeks, all the tapes would have been in a landfill.”

Yet after that heroic act, things ground to a halt while circumstances intervened in the players’ lives. One daunting factor was the sheer quantity of material produced by Shipp’s label. “My Subaru wagon was filled up with tapes,” says Hurtt. “It was massive. Then Scott Bomar was generous enough to say, ‘I’ve got this room in my studio I’m not even using. You can put everything in there.’” And there they sat — for years.

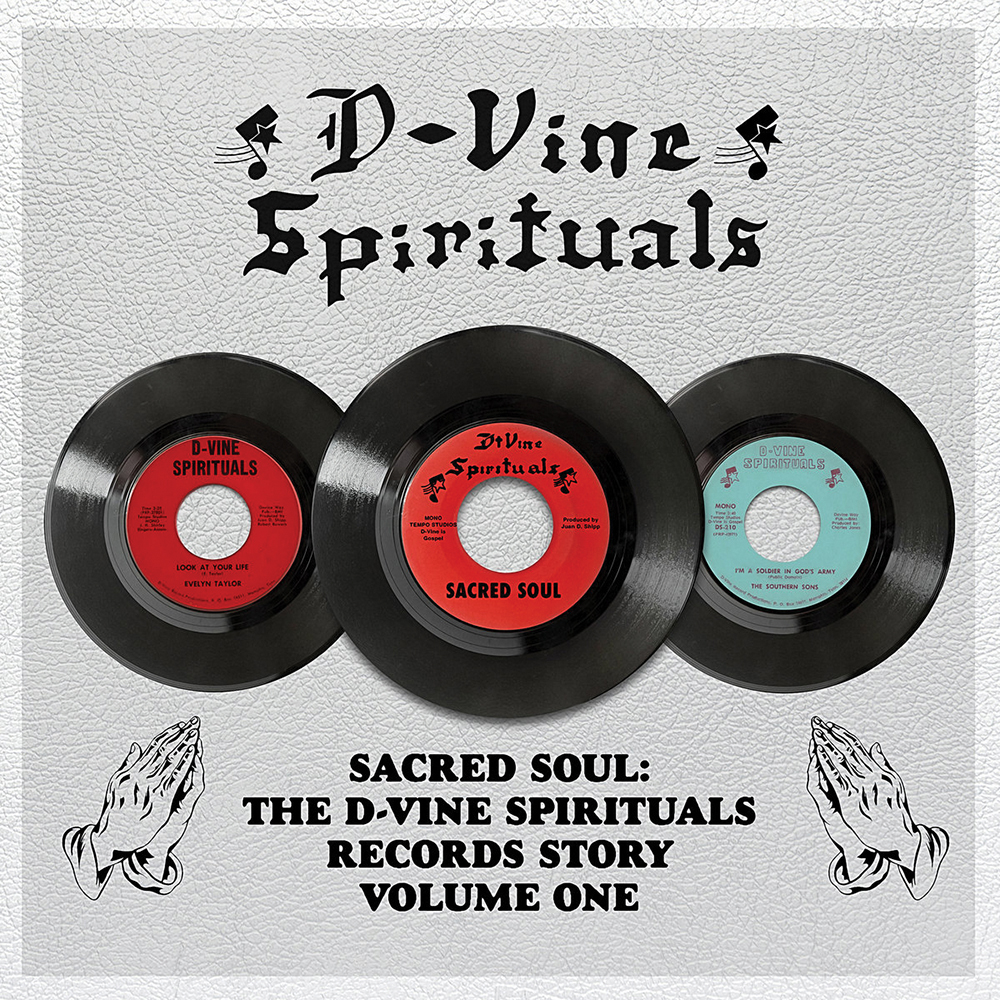

Enter Bruce Watson of Fat Possum and Big Legal Mess Records. Having learned of the tapes from Bomar and spoken with Hurtt, he was beginning to imagine the possibilities. “That gospel stuff from the ’60s and ’70s is just so amazing,” Watson says, “and I just don’t hear that in modern gospel music. I wanted to create a Memphis-based label that concentrated on recording gospel, and try and make it sound like it was recorded back then. And also reissue stuff. So I contacted Pastor Shipp at the beginning of 2019 and said, ‘Look, I would love to buy the rights to the D-Vine Spirituals catalog and kick-start this new label.’”

Retrieving the tapes from Bomar, he began going over the material, preparing for his new venture, Bible & Tire Recording Co. “We transferred 150 master tapes, and they were all in pretty good shape still. I didn’t need to bake any of them,” says Watson, referring to the heating method used to restore old tape stock.

“Bruce and I met, and he seemed like a very nice guy,” says Shipp. “That was in 2019. It was 2007 when I first talked to Mike! And then it took six or eight months for us to transfer the stuff to the computer. We worked on it for a long time before we did anything,” he muses.

A Parallel Universe

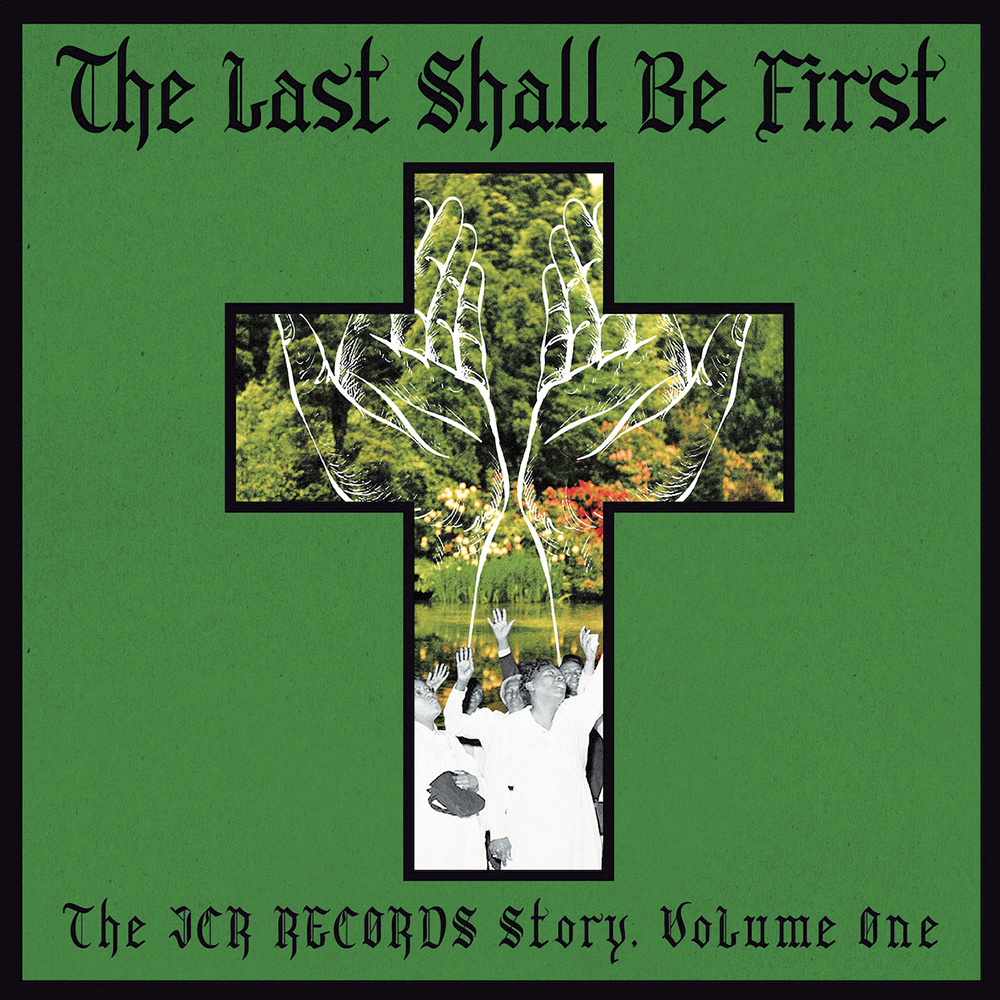

Gradually, the material has been seeing the light of day on various Bible & Tire releases, including a compilation of Elizabeth King’s tracks as well as selections from a subsidiary of D-Vine Spirituals, JCR Records. The label has also brought King and Elder Jack Ward, two of D-Vine’s greatest talents from the very beginning, back into Watson’s studio for contemporary albums of their own. And finally, this year has seen the release of Sacred Soul: The D-Vine Spirituals Records Story, Volumes 1 & 2, with four more volumes in the works.

The Bible & Tire compilations include extensive liner notes by Hurtt, but they barely convey the shock and wonder he feels at seeing this saga come to fruition. “What’s amazing about this stuff,” he notes, “is that the ’70s was really a golden era for gospel music, but not in the sense that it sounded like ’70s music. It always had one foot in the quartets. That quartet sound is what I’m attracted to, at least. And their whole approach was not to dismiss modernism, but to still embrace tradition. A certain kind of harmony and approach was beautifully preserved, but not mired in the past.” He points to certain progressive elements in the production, from wah-wah guitar to the raw, stomping funk of some tracks.

“Not every city has that underground gospel scene that we’re lucky enough to have in Memphis,” Hurtt says. “If you didn’t have your ear to the ground, you wouldn’t even know it exists. There’s this whole parallel universe, and it’s pretty much the coolest thing that is going on. But nobody knows about it. It’s not like this music’s not moving ahead, but its roots are deep. And that was what Pastor Shipp always told me he was trying to achieve with D-Vine. Keeping the roots of it — the harmony and quartet sound — while adding some modern touches. That’s the magic of D-Vine Spirituals. It’s of two times, essentially. And therefore out of time.”