The two attorneys met, as they’d agreed. They sat side by side and hefted the two large, accordion file folders onto the desk before them and began pulling out stacks of documents. It was not the showy legal work of television dramas; it was the inescapable tedium of reviewing the state’s evidence in a murder trial that had ended five years before.

The work dragged on. Nothing surprised them, until something did.

Here’s how Doug Carriker, a prosecutor in the Shelby County District Attorney’s Office, remembered the discovery in a court hearing last year.

“A: On the outside of the manila envelope, about — just a standard size, maybe four inch by four inch yellow sticky pad note and it had language … something to the likes of ‘not turned over’ or ‘do not turn over to defense,’ and it had initials at the bottom and a date of, I want to say 2005 or so.

Q: Do you recall what the initials were?

A: ‘A’ — it was ‘A’ something, whatever Miss Weirich’s middle name is. A, something, W.”

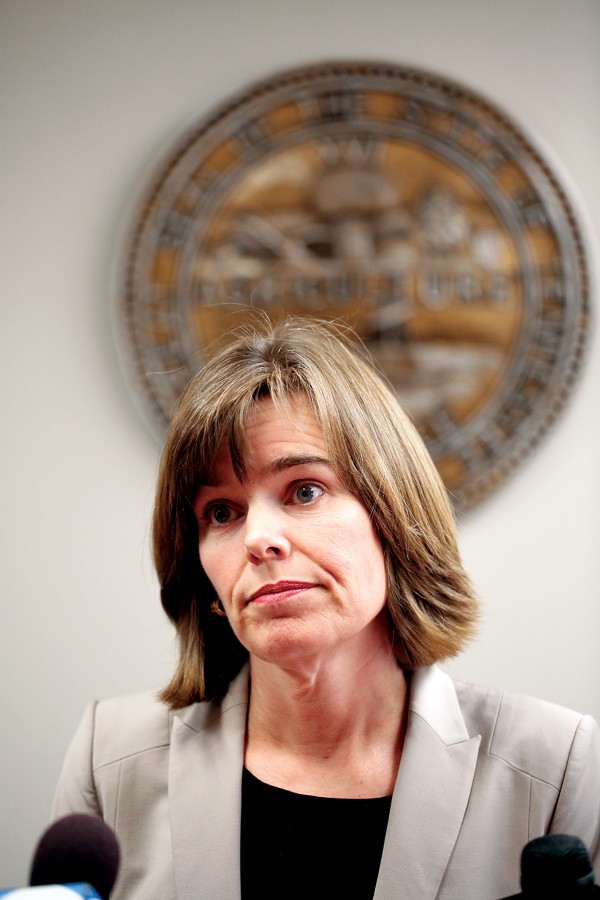

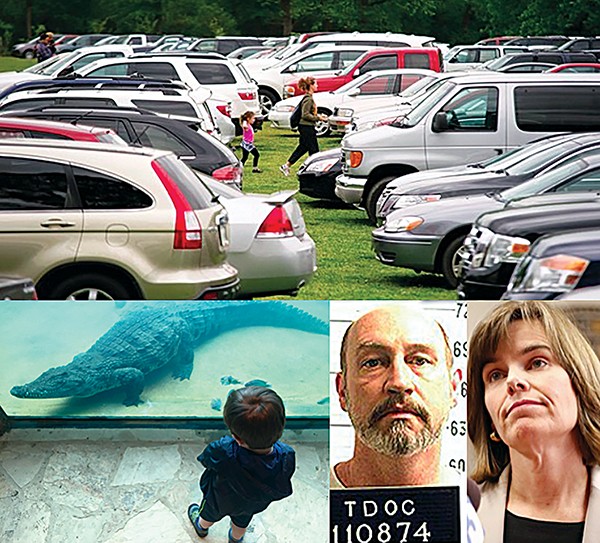

Carriker and defense attorney Taylor Eskridge had met to review all of the evidence Amy Weirich (now the Shelby County District Attorney General) and her team used in 2005 to convict former middle school principal Vern Braswell of killing his wife.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

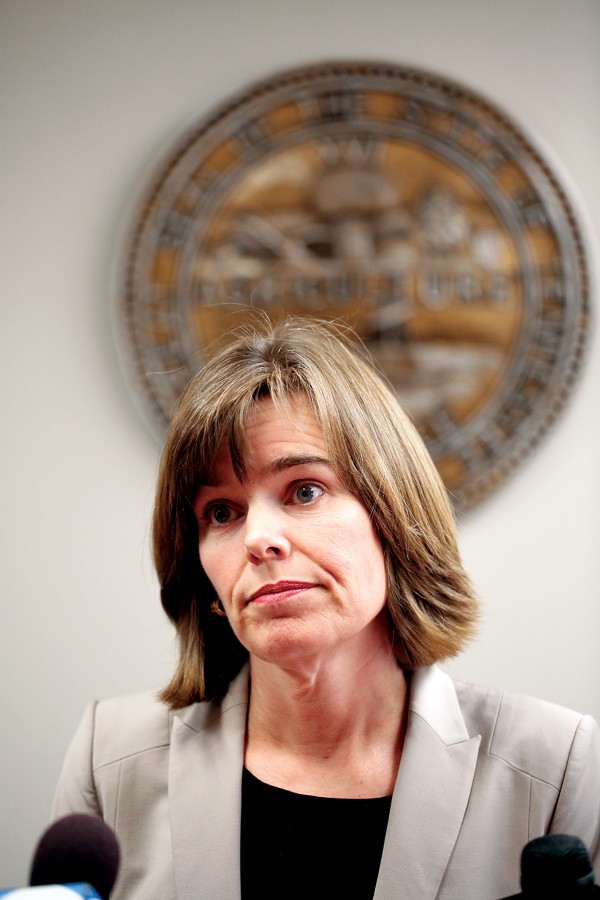

DA Amy Weirich

Eskridge testified that the words on the sticky note were written boldly with some kind of broad-tipped marker. The words shocked Eskridge and abruptly stopped the attorneys’ work session. Here’s how she remembered that moment of discovery:

“…As we were going through, we were like, he was like ‘What’s this?’ And I was like shocked. …(The envelope) was closed with a seal that I recall. …What caught our attention was that it had some kind of note that made it clear that the defense couldn’t see it. … I think it said ‘do not show defense’ or something like that. But it was something that caught both of our attention.”

Prosecutors choose the evidence they hand over to criminal defense attorneys. But federal law (called the Brady Rule) mandates prosecutors hand over any evidence that could help prove the innocence of the accused (called exculpatory evidence). The statements from Carriker and Eskridge — two attorneys who once plotted the other’s defeat in a high-profile murder trial — both point to a possible violation of this law.

But it is not the first time Weirich’s office has come under fire for Brady violations. Two past murder cases are scheduled to be heard again in court this year in retrials that were won in part because of Brady violations. In fact, the issue was raised again just this week as Weirich recused herself Monday from the new trial for Noura Jackson, who was convicted of killing her mother.

The discovery of the envelope back in 2011 is still rippling through the decade-old murder case. Braswell is now an inmate at the West Tennessee State Penitentiary, but he’s back in court with a new attorney and a set of new claims that he hopes will win him another trial.

That discovery was at the core of the controversy for Weirich that boiled over right before the Thanksgiving holiday, when Weirich was ordered to take the stand before Shelby County Criminal Court Judge Paula Skahan. Weirich said she made all required evidence available to Braswell’s attorneys. And as for that manila envelope with the bombshell sticky note:

“If there were such an envelope and there were such a notation, no, I don’t recall doing that and that was not and is not my practice,” Weirich said in her testimony.

If Weirich did write those words, it’s possible she violated Braswell’s constitutional rights and broke one of the most basic rules governing prosecutors, which could in turn cost taxpayers thousands of dollars for a new trial. If the original manila envelope and the sticky note are ever found, they could help set free a convicted killer. And it might fundamentally change the public’s opinion of an elected official who just won reelection by a landslide.

A Trend Emerges

At the very least, the alleged statement on that sticky note raised again a troubling charge: that Weirich and some of her top attorneys have hidden evidence in big murder cases. At least two murder cases are set to be reheard this year because either Weirich or an attorney from her office kept evidence from defense attorneys.

Noura Jackson

• Noura Jackson was convicted of stabbing her mother at least 50 times in 2005. A new trial was ordered for her in August because the Tennessee Supreme Court said Weirich did not give Jackson’s attorney a key witness statement and committed other violations during the trial.

Andrew Hammack was a friend of Jackson’s. She named him as a possible suspect in the murder of her mother, and the police suspected him, too. Hammack told police Jackson called and texted him from her house the night her mother was murdered. His testimony put Jackson at the scene of the crime on the night of the crime.

He later recanted his statement, telling police he was high on ecstasy on the night of the murder and that he didn’t even have his phone that night. Weirich did not give the recanted statement to Jackson’s attorneys.

In a unanimous opinion from the Supreme Court, Justice Cornelia Clark wrote that it was “difficult to overstate the importance of this portion of Mr. Hammack’s statement” because Jackson’s attorneys could have used it to question the police investigation and “to argue that Mr. Hammack himself was a plausible suspect.”

Jackson’s new trial was also granted because of Weirich’s blustery closing argument. In it, she turned to Jackson and dramatically implored the defendant to “just tell us where you were (on the night of the murder).” Jackson had decided not to testify in her defense and her attorneys said Weirich’s imperative statement directly to Jackson violated her right not to testify.

• Michael Rimmer was convicted in two trials (in 1998 and 2004) of killing a hotel clerk whose body has never been found. He was granted a new trial in December 2013 because Thomas Henderson, a high-placed, veteran attorney in the Shelby County District Attorney’s office, did not give relevant evidence to Rimmer’s defense attorneys.

For this, the Tennessee Supreme Court’s Office of Professional Responsibility ordered a public censure of Henderson. The censure was a “public rebuke and a warning to the attorney, but does not affect the attorney’s ability to practice law,” according to a news release issued from the office at the time. Henderson also had to pay the court costs associated with the censure, which totaled $1,745.07.

Henderson argued the state’s case on both of Rimmer’s trials. Weirich pulled him from the new trial after the censure. She called this a “punishment” and a “huge step, and it was a tough conversation to have.” She ordered no other discipline.

• Now comes the case of Vern Braswell, who claims he didn’t murder his wife, Sheila Braswell, in 2004. He says they had rough sex the night she died, and he choked her until she passed out. But he claims she liked it that way, that the couple had a kinky sex life, and on the night of her death she asked for a “fixie,” their term for a round of erotic asphyxiation.

But Braswell has a history of choking women as a hostile act, according to testimony recorded in court papers. He also had been seeing another woman right up until the time of his wife’s death. Divorce papers were found in Sheila’s purse after her death, and she had sought an order of protection from her husband.

On the night of her death, Braswell says he and his wife were in the couple’s jacuzzi. They got intimate and moved to their bedroom “as a result of inadequate lubrication” in the jacuzzi. They got out of the bath and into the bedroom and had sex, sex that included a “fixie.” Afterward, Sheila complained of cramps in her abdomen and got back into the couple’s jacuzzi.

Vern said he went to bed, where he waited for a show called Erotic Confessions to come on. He said he fell asleep at about 1:30 a.m. When he woke at about 3:40 a.m., Sheila was not in bed. Vern Braswell claimed she was in the bathtub with the jacuzzi jets still running. She showed no signs of life, her face and head were submerged in the water. He said he tried to remove her from the tub but couldn’t. He said he called 911, then a police friend of his, and then other family and friends to try to get help.

Three courts have ruled on the facts in the case. Braswell was convicted and lost two appeals. It may be unlikely that another court would hear those details and come up with a different verdict. But his lawyers do have some new facts and a new angle. They want to prove that Braswell and his wife did, indeed, have a kinky sex life and that choking was a part of that. It’s a defense that his former attorney, Javier “Jay” Bailey, crafted but didn’t initially like, he said in hearings in November.

Bailey said he feared there would be a “creep factor” for a jury “thinking of a second grader’s principal choking a woman he’s having sex with.” But now, years after the original conviction, his attorneys are trying to prove exactly that.

Braswell’s new attorneys say prosecutors had an unfair advantage in the original 2005 trial. They did not release statements from potential witnesses in the case that could have proved Vern and Sheila Braswell had a kinky sex life. And then there’s that one big unknown: the evidence in that manila envelope that the two opposing attorneys say they saw.

A National Problem?

Shelby County is hardly alone when it comes to cases of prosecutorial misconduct, especially Brady violations (hiding exculpatory evidence from defense attorneys).

The University of Michigan Law School’s National Registry of Exonerations said in a 2013 report that 43 percent of wrongful convictions in 2012 were attributable to prosecutorial misconduct, including Brady violations, charging a suspect with too many offenses, pressuring witnesses not to testify, relying on fraudulent forensics experts, making improper or misleading statements to the jury, and more.

“The overwhelming majority of lawyers who choose to become prosecutors are ethical,” said a 2013 white paper by the Maryland-based Center for Prosecutor Integrity (CPI). “But powerful incentives — political ambitions, media pressures, and a culture of prosecutorial infallibility — can serve to induce prosecutors to act unethically.”

Wrongful convictions were once less common. But with the advent of post-conviction DNA analysis in the 1980s, many convictions were overturned. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and Chicago Tribune brought prosecutorial misconduct to the national stage with separate high-profile investigative reports in the 1990s.

The national audience on the issue grew wider in 2007 when the North Carolina State Bar disbarred a district attorney there for “dishonesty, fraud, deceit, and misrepresentation” in the widely televised Duke University lacrosse case. This is all according to CPI’s white paper called, “Epidemic of Prosecutor Misconduct.”

When a case goes to a retrial due to the misconduct of government prosecutors, the cost of government goes up. The Center for Prosecution Integrity’s study did not put a dollar amount on the cost of retrials, nation-wide. But a 2008 investigation by The Dallas Morning News put the cost to Texas taxpayers at $8.6 million from 2001-2008. In Illinois, wrongful convictions on violent crimes from 1989 to 2010 cost taxpayers $214 million and imprisoned innocent people for a total of 926 years, according to a joint investigation by the Illinois-based nonprofit watchdog group, Better Government Association, and the Center on Wrongful Convictions.

Brady violations returned to the national spotlight in a 2002 federal case against a Spokane man who made ricin, a deadly poison.

Kenneth Olsen was convicted by a federal jury of knowingly developing the biological agent for use as a weapon, according to the lawsuit. Olsen appealed for a new trial because while he admitted he made the poison, he said he didn’t intend to use it as a weapon.

Whether he did or didn’t hinged on the work of Washington State Police Forensic Scientist Arnold Melnikoff. But his work had been sloppy in the past, and at the time of the appeal, an investigation of the scientist had been conducted.

The U.S. Assistant District Attorney prosecuting Olsen’s case downplayed the investigation in “scope, status, and gravity.” The investigation was over, but the prosecutor told Olsen’s attorney it was ongoing, and “there is nothing further you should know about.” The investigation was, in fact, damning and Melnikoff was fired.

A federal judge requested that the case be reheard. A vote was taken by the panel of judges in the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, and Olsen did not win a retrial. Chief Judge Alex Kozinski wrote a scathing dissent of the decision, declaring “there is an epidemic of Brady violations abroad in the land.”

“[The decision] will send a clear signal to prosecutors that, when a case is close, it’s best to hide evidence helpful to the defense, as there will be a fair chance reviewing courts will look the other way, as happened here,” Kozinski wrote in December 2013. “A robust and rigorously enforced Brady rule is imperative, because all the incentives prosecutors confront encourage them not to discover or disclose exculpatory evidence. This creates a serious moral hazard for those prosecutors who are more interested in winning a conviction than serving justice.”

Who Prosecutes the Prosecutors?

In Tennessee, the very short answer to that question is the Tennessee Supreme Court’s Board of Professional Responsibility, which was created by the court in 1976 to supervise the ethical conduct of attorneys practicing in the state.

The board is comprised of nine appointed attorneys and three appointed lay members. It now includes Memphians Margaret Craddock, former director of the Memphis Inter-Faith Association, and Odell Horton Jr., a partner at Wyatt, Tarrant & Combs.

The board also publishes ethics opinions, hosts an ethics hotline, runs a consumer assistance program, and more. But its main focus is disciplinary enforcement of attorneys.

In fiscal 2013, the board oversaw 21,142 active attorneys in the state. It received 1,474 complaints about attorneys and saw 79 formal cases filed.

Anyone can file a complaint on an attorney, says Sandy Garrett, the board’s chief disciplinary counsel. But, she says, about a third of the complaints come from other lawyers and judges, “because they have a duty to report misconduct.” Should the board decide a complaint merits the status of actual misconduct, a trial is held, similar to that of a civilian court case, with discovery, witnesses, evidence, proof, and even subpoenas.

After the trial, the board can dismiss the case or sentence the accused attorney to punishments ranging from a public censure (which Henderson received last year) to disbarment.

District attorneys are governed by the same rules as other attorneys, Garrett says, and are also bound by a set of special rules including mandates on probable cause and disclosing exculpatory evidence to defense attorneys.

“District attorneys have a tremendous amount of discretion, which is what we try and explain to folks again and again and again,” Garrett says. “Which is not to say they should be engaging in misconduct, but we get a lot of complaints about charging decisions, about whether or not a district attorney is ‘picking on somebody,’ or vice versa, that they are not charging somebody that somebody else thinks should be charged.”

Sanctions against prosecutors are relatively rare. The Center for Prosecutor Integrity says that between 1970 and 2003 there were 2,102 cases in which prosecutorial misconduct infringed on the constitutional rights of defendants. Fewer than 50 public sanctions were imposed on those prosecutors.

“Professional discipline is rare, and violations seldom give rise to liability for money damages,” wrote Ninth Circuit Court Chief Judge Kozinski in his 2013 dissent on the Olsen ruling. “Criminal liability for causing an innocent man to lose decades of his life behind bars is practically unheard of.”

Kozinski pointed to a 2013 case in Texas in which former prosecutor, Ken Anderson, suppressed evidence in a trial and sent an innocent man to prison for 25 years. Texas settled civil and criminal charges against the attorney by having him forfeit his law license, serve up to 10 days in jail, pay a $500 fine, and perform 500 hours of community service.

Noura Jackson

The Next Step

It’s unclear what — if anything — will happen to Shelby County District Attorney Amy Weirich in light of the latest allegation of Brady violations against her office.

One thing’s for sure, though, that original manila envelope and its potential bombshell sticky note are long gone. Carriker, the prosecutor who originally discovered the evidence, said he and Eskridge didn’t open the envelope that day back in 2011. He wanted permission from his superiors first.

The envelope went back into the state’s file. Carriker was assigned to another unit and never saw the envelope again. Neither did attorneys for Braswell. But they want it now and will likely use its absence in their case for a new trial.

“I don’t know what’s in that envelope and that envelope is gone,” said Braswell’s new attorney, Lauren Fuchs, in court last year. “It disappeared. It’s no longer in the file. I’ve asked for it. They’ve looked for it. It’s gone.”

Another envelope and sticky note showed up in the Braswell hearings last year, but Carriker said the envelope wasn’t the same and Eskridge said the note didn’t read like the one she remembered.

The new sticky note reads: “I am NOT giving these items in discovery. 8-22-05 APW.” Then there’s a later notation on the note that reads: “12-6-05 (Investigator Jencks’ statements) of witnesses who testified were turned over at the appropriate time.”

Whether or not the new envelope and sticky note are the originals, Judge Skahan deemed them important enough last year to be entered into evidence. In making sure that the new evidence stayed put, she called for a court officer — not either of the opposing attorneys — to make copies of it. New court dates in the Braswell case are scheduled for March and April.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks