It seems like only yesterday that everything came crashing down around us. Nearly everyone in Memphis this February 3rd was startled at some point by the sound of a tentative, icy crackling, followed by seconds of silence, then the impact of a limb or an entire tree. And there were often other noises: the squeal of crushed metal, the snap of sparking wires, or the crunch of splintered wooden beams, as cars, power lines, and homes fell victim to The Overstory.

In Richard Powers’ novel of that name, the trees speak to humanity, putting such calamity in perspective:

All the ways you imagine us … are always amputations. Your kind never sees us whole. You miss the half of it, and more. There’s always as much belowground as above.

That much was vividly illustrated during February’s storm, when an especially heavy thud, more felt than heard, led me to peek out at the house behind me. An entire tree, unbroken, had been uprooted by the sheer tonnage of ice it had to bear, pulling its roots from the ground, lifting the concrete slabs of a driveway with them as the trunk sank into the roof. Removing it took days, the closing of the street for massive equipment, and untold thousands of dollars.

Yet the massive tree damage from that day, and its aftermath in lost power and time, is but one pole in the ongoing dichotomy that Memphis must confront over and over again, caught between damning our trees and praising them. Consider another arboreal moment from less than a year before, when local social media was inflamed with outrage as some beloved neighborhood landmarks “disappeared.”

Last June, local filmmaker and activist Mike McCarthy wrote on Facebook, “If anyone cares to drive down East Parkway right now you can see the removal of every single oak tree from the former Libertyland/Fairgrounds green space.” Indeed, in less than a day, an entire glade had violently vanished, and the comments that followed revealed a deep sense of betrayal: “Atrocious,” “It was depressing,” and “Memphis is owned by developers who DGAF about anything except what money they can make. The mayors and city council members are their enablers.”

Our trees engender both fear and adoration in us, and our endless dance between these two extremes makes one thing clear: It’s time for Memphians to own their overstory, and the best route to that is a deeper dive into the world of urban forestry.

The Unsung Boon of Trees

As it turns out, many Memphians are already taking that deep dive, and those who have cultivated their inner citizen-arborist are quietly leading a minor revolution in tree care and tree cognizance. As with so many things horticultural, the Cooper-Young neighborhood is leading the way. Judi Shellabarger runs the Cooper-Young Historic District Arboretum, and she vividly recalls the day the Libertyland oaks were destroyed.

“That was done in one day,” she says. “They always do it quick. But those trees were valued. They helped keep that area from flooding. That’s one of the main purposes of planting trees, is to prevent flooding and erosion. Plus, they would have given great shade out there, on whatever courts or football fields or baseball fields they’re building. But I was talking to two city council people about that, and one of them said, ‘Trees don’t bring money to Memphis.’ And I thought, ‘Yes they do!’ When that floods all up and down Southern Avenue, they’re going to be sorry. Those roots hold down that soil and collect water as it’s running off.”

Mike Larrivee, another Cooper-Young resident and founder of the Compost Fairy program, also saw it as a biodiversity tragedy. He puts the clear-cutting down to “the confluence of greed and ignorance. That clear-and-grub mentality instead of, ‘What can we save? How can we create economic value in this development?’ Statistically, there’s tremendous value in having mature trees on a piece of property, regardless of its use. Just their presence creates value. And that area around Libertyland was sort of an ad hoc arboretum. There were 43 species of tree there, in that little spot. It was tremendously biodiverse.”

The inherent value of trees is a given among a growing demographic in Memphis that wants to preserve and propagate them, and they contrast the short-term gains of a development deal with the very real benefits that urban forestry studies have proven. A 2017 study by The Nature Conservancy, “How Cities Can Harness the Public Health Benefits of Urban Trees,” detailed multiple studies, including peer-reviewed and longitudinal research projects, that demonstrate the many blessings of an overstory. Those include both mental and physical health benefits, from mitigating summer air temperatures and reducing air pollution, to increasing immune system function and decreasing stress levels.

Land of a Thousand Arboretums

Many tree aficionados simply start with their beauty and the immediate benefits of shade. Those factors are likely the driving forces behind the community arboreta that have sprung up throughout Memphis in recent years. As the Cooper-Young Historic District Arboretum reveals, setting up such a program is largely driven by the Tennessee Urban Forestry Council (TUFC), and they are facilitating the process wherever they can.

Laurie Williams, of the Memphis Botanic Garden, describes the process: “The TUFC oversees the entire arboretum program across the state. We were the first Level 4 arboretum in the western part of the state, and we then petitioned to be a center of excellence. That means we not only have a Level 4, with all those requirements, but we also help other arboreta become certified. There are different requirements: Level 1 is just 30 trees with labels on them. Level 2 is 60 trees and a map. And Level 3 is 90 trees and other steps, and by Level 4, you have to have a newsletter in addition to all those other steps, and trained people that can give tours.”

With no small amount of pride, Shellabarger describes how that’s played out in Cooper-Young. “This is our fifth year as an arboretum, and we’re now a Level 3. We have over 112 trees altogether, and we’re working toward more. It’s mostly in front of people’s homes, in their front yards. But we do have some trees at Peabody Elementary School, and some at Cooper-Young businesses. And we have a lot up at the Spanish-American War Memorial Park. What we’re doing in the next two years is, we’re working with the City of Memphis Parks Division to redo what we call the Park Annex behind the Spanish-American War Park. There’s an acre of land that was railroad land, and we’ve been trying to get that cleaned up and replanted with native trees on the north side. And on the south side, we would like to have a food forest with fruit and nut trees.”

While Cooper-Young was one of the first arboreta, many more are in the works. Williams rattles off at least a dozen parks, campuses, and neighborhoods that have already curated arboreta or are working on it. But it can be a costly process, and she offers the Vollintine-Evergreen Community Association as a case in point. “We’ve been working with the VECA arboretum since 2008,” she says. “They tried to begin an arboretum, but when you have old trees, you have limbs that need to be taken care of. And it ends up coming down to money. Certified arborists are not cheap when they come out to trim trees. So VECA is really struggling. Of course, we’ve had so many storms, so there are unsafe trees. And the TUFC won’t certify until the main path is clear of dangers. So that’s why VECA is still struggling.”

We Are the Champions

The Memphis Botanic Garden facilitates such community-level initiatives, but there are other, more individualized ways it contributes to the urban forest. Every fall (September 14th through October 12th this year), they team up with the TUFC’s West Tennessee Chapter to host an Urban Forestry Advisor’s Class. As Williams explains, “Eric Bridges, who used to be the naturalist for Lakeland [and] is now the operations director of the Overton Park Conservancy, teaches quite a bit of our classes and talks about wildlife corridors, for example. Instead of everybody having two and a half acres and ripping out the native trees and putting in a bunch of Japanese maples, keep corridors for wildlife to survive, so they don’t have to go into heat islands. Eric does a really good job. And then Wes Hopper teaches quite a bit. We do a lot of tree identification and teach people how to plant trees. And we talk about the arboretum and championship tree programs.”

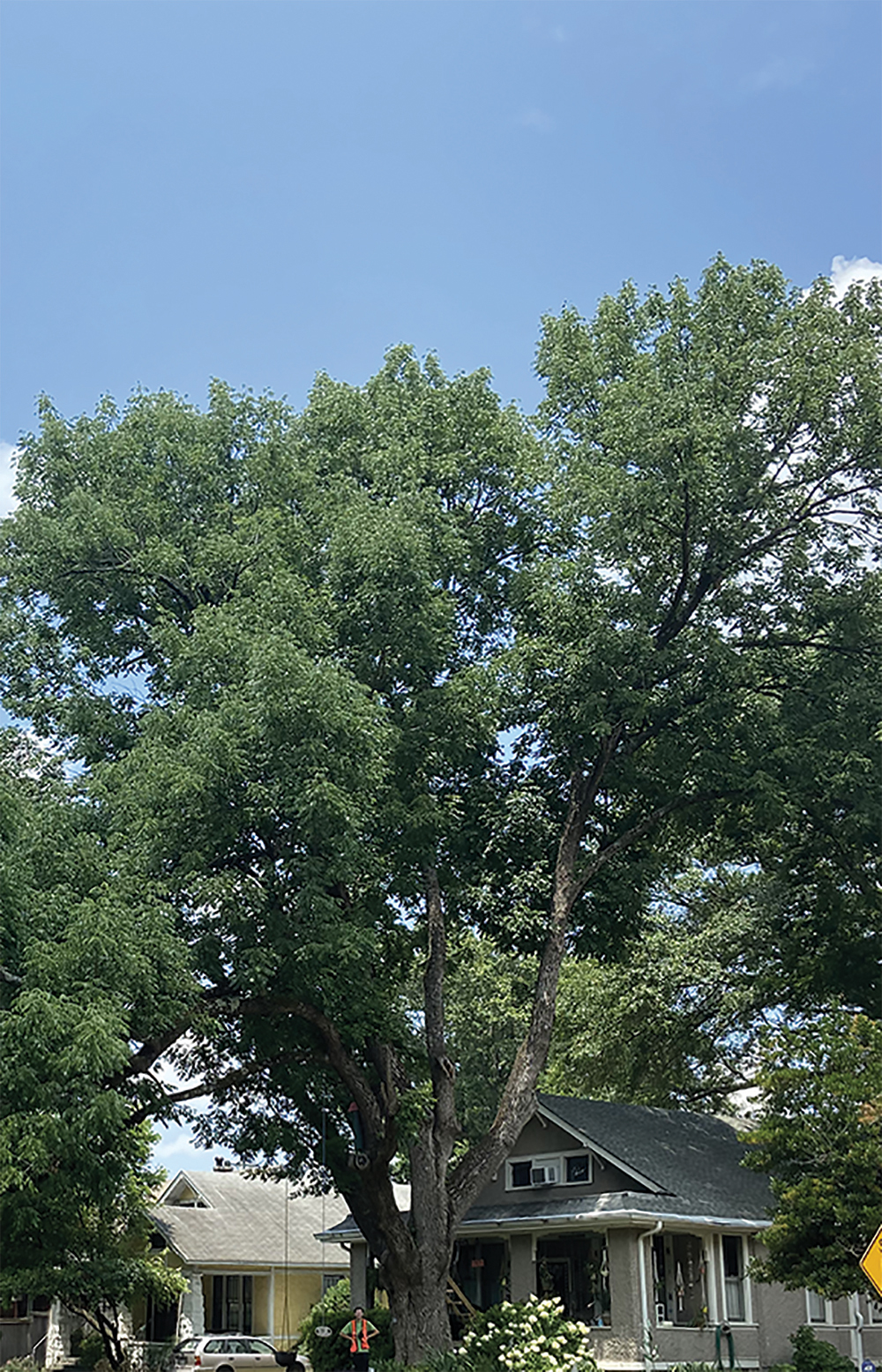

The latter program is yet another way that the TUFC supports an appreciation of the overstory. “Champion” trees are the largest, healthiest examples of a particular species in the state, and Memphis boasts several. Shellabarger describes the process: “We have a championship tree team here in Shelby County, and we’re not experts, but we’re from the West Tennessee Chapter, and we go out and measure the tree and take pictures of it and mark its location with the GPS and send it to the state. The University of Tennessee will send students down here to measure it for us, and they’ll review all the other trees in the state and pick the winners.”

Cooper-Young boasts several, all identified with signage as per the requirements of a TUFC-approved arboretum. “We have six or seven state champion trees in Cooper-Young,” says Shellabarger. “There’s a champion California incense cedar at 2052 Nelson. My favorite tree, though it’s not a champion, is the Carolina silverbell, and it should be flowering probably in the next two weeks. It has little white flower-shaped bells, and it’s at 1991 Oliver.”

Tree City, U.S.A.

While the TUFC and its West Tennessee Chapter have a hand in many of the arboreal pursuits in this area, the networks of urban forestry activists run on a national and international scale as well. Memphis has officially been designated a “Tree City, U.S.A.,” by the national Arbor Day Foundation, but it was Germantown that nabbed that honor first. Williams explains: “Memphis became a Tree City, U.S.A., a few years ago, and to do that, a city has to have a Tree Board and an Arbor Day celebration. There are some requirements. It takes a long time to achieve that Tree City status. Nashville’s been that way for quite a while. Germantown, also. Memphis was behind that curve. There are some requirements about money, and there are cities that have more money available than others. Because you have to have a certain amount per capita.”

That may explain why Germantown led the way. Hopper points out that “Memphis has had a Tree Board for maybe eight years, but Germantown’s had a tree board for 30. And we are also designated as a Tree City of the World. That was a new program through the Arbor Day Foundation and the Department of Agriculture when I started here. Germantown was the first city in Tennessee to be considered a Tree City of the World, in 2019. The program is managed by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the Arbor Day Foundation.”

Tree Equity

And yet arboreta, Tree City designations, and champion trees are not just for relatively well-off neighborhoods who can fund arborists. A parallel movement is afoot that starts with other benefits outlined in the Nature Conservancy report and elsewhere. These are sociological benefits that show a marked correlation with the amount of tree growth in an area. Wes Hopper, Germantown’s natural resources manager and city arborist, says the current term for this is “tree equity.” As he distills the concept, “If you have a low tree equity in your district, you’re going to have a higher poverty level. If you have a high tree equity, like a rating of 85-90, you’re probably going to have a higher social standing in that area.” The website treeequityscore.org presents an interactive map that shows the tree equity rating of any given locale. Unsurprisingly, poverty-stricken areas of Memphis have scores hovering around 40.

Mike Larrivee is part of a team that’s trying to change that. “There are proven benefits of urban tree cover, like fighting blight and pollution and littering, and discouraging vandalism and vagrancy, that go above and beyond the ecological services,” he says. South Memphis Trees is a local program planning to go beyond arboreta with the planting of new trees on a massive scale. Larrivee and others are trying to fuel that movement. “For the South Memphis Trees project,” Larrivee says, “the Wolf River Conservancy, the Native Plant Initiative, and Compost Fairy/Atlas Organics just co-hosted an event with Urban Earth and potted up 3,500 saplings for the urban tree farm. We’ve put tons of trees in the ground in the last three years that we’ve been working together. Ryan Hall at Wolf River Conservancy is a tank! There’s no telling how many thousands of trees are standing as a direct consequence of his engagement.”

Playing the Long Game

Indeed, champion trees aside, tree-planting seems to be the key to ensuring the role of trees in the city’s future. For one thing, as traumatic as downing mature trees can be, that’s sometimes necessary, leaving new growth as the only possible response. That’s Wes Hopper’s philosophy, as he manages tree-related issues for Germantown, not to mention sitting on both Germantown’s and Memphis’ Tree Boards and being a board member of the TUFC.

“Having all those connections, I ended up working with the forestry division of MLGW, as a liaison between property owners and the MLGW tree crews, trying to help clients understand the importance of having that clearance from the utility wires. The best thing we could do would be to remove a tree and plant a tree somewhere else. That didn’t always go over so well. Tree removals can be a touchy subject for some people, but a lot of times, it’s best just to remove the tree. Because the electricity is going to win. If you plant a big tree by the utility lines, sooner or later your tree’s gonna get whacked.”

Such a long-term approach helps us to understand both the ice storm wreckage and the trauma of losing beloved trees, says Hopper. “Those trees at Libertyland? A lot of them were healthy, but a lot of them had a poor root system,” he says. “I went out to look at the trees, even the big oak trees, and I saw a lot of root rot on them.

“So we have to involve the community,” Hopper continues. “If they have an issue with our urban forest, someone needs to take action. You can go to Parks and Recreation, go to a Tree Board meeting and say, ‘I want to get a Tennessee Agricultural Enhancement Program (TAEP) grant to get trees replanted in place of those that got removed.’ The TAEP grant is an environmental grant through the state forestry division and you apply to plant a certain amount of trees in that area. Sometimes it just takes one person to pull the team together and make it function. You take a person like Judi Shellabarger, that lady gets things done!”

If some find that unsatisfying, such community involvement may also help build on what’s already in place. For now, the Tree Board can make recommendations and suggestions, but a groundswell could elevate the body’s importance. And it will take political pressure to value trees at the level of policy. Mark Follis, owner of Follis Tree Preservation and member of the Memphis Tree Board, served briefly through a period when the city government deemed trees more worthy of attention. “Memphis had a city forester until budget cuts in 2005. But he had no money. He had the position, but no budget. Then for three years, more recently, we had a grant and I was the city forester, but only on a part-time basis while the grant lasted. There isn’t a permanent position now.”

As Mike Larrivee says, it boils down to political will: “Memphis gets compared to Detroit a lot because our demographics and economy are similar. But for years, Memphis did not have a paid arborist or tree team until Mark got that part-time funded position. By comparison, the city of Detroit has a tree team of 20 on the city payroll. Same size city, with the same sort of density and coverage of urban canopy, and they’ve had an urban tree team for 100 years. So we just do not prioritize or allocate resources in a way that’s befitting the assets we have.”

The West TN Chapter of the TUFC will hold its annual meeting at the Memphis Botanic Garden on Thursday, April 21, at 1 p.m. Bill Bullock will speak on battling invasive plants in Overton Park’s Old Forest.