Change is in the air. That is a given. That’s the message of the slight but obvious up-tick in early voting statistics over the equivalent period four years ago. That is what the pollsters and pundits are telling us as they assess the chances of prevailing for this or that candidate for mayor in the 2015 Memphis city election, which is just two weeks away, on October 8th.

So will the race for City Court Clerk, unique on the ballot for its lack of any real bellwether content, and so will those for the six of the 13 City Council seats selected by voters at large, the results of which races may well turn out to have long-term significance indeed.

The change of direction may not be obvious then. There are seven other City Council races decided by geographic district. These are discussed on page 12, and several of these may persist in uncertainty for six more weeks — until the runoff date of November 19th.

But meanwhile, we’ll likely have a good sense of the shape of our future from the election of our next mayor. The next mayor could be the same mayor we already have, of course — A C Wharton, who signaled change when he came into City Hall via the special election of 2009. Back then, his supporters were chanting his slogan of “One Memphis,” to define the shift from the mayor he succeeded — Willie Herenton — a great change-maker himself when he narrowly won election in 1991 as Memphis’ first elected black mayor, and an ambitious reformer until four complete terms and a portion of another finally wore him down into resignation (both figurative and literal).

Has the time come, after only six years in office, for Wharton to pass from the scene as well? Manifestly, he doesn’t think so, but the voters might. A dozen private polls, formal and informal, suggested that possibility, including a public one, done by Mason-Dixon for The Commercial Appeal that was taken very seriously in its prognosis of a tight race, that being almost a toss-up between the mayor and his closest challenger, Councilman Jim Strickland.

Strickland, a two-time budget chairman who made his reputation as a champion of austerity, has been running for mayor in his mind ever since his election to the council on his second try in 2007. His thinking was sped up by a snarled and straitened city fiscal situation that drew a pointed rebuke from State Comptroller Justin Wilson in 2013 and in the last year forced service reductions and severe cuts in employee benefits and pensions.

The remedy Strickland has proposed is less a new vision than a prescription for tightening up and cracking down. Mindful of the violent flash mobs of 2014, he calls for tougher containment action against teen perpetrators. He wants Blue CRUSH writ large and would lobby, too, for elevating repeat domestic abuse to the status of felony. He would rid the city of blight, and he talks of stricter and more transparent accountability standards for public employees.

In the election-year environment, Strickland has downplayed his erstwhile fiscal concerns, perhaps in view of public uneasiness regarding cuts in employee benefits and many resignations in the ranks of the city’s first responders.

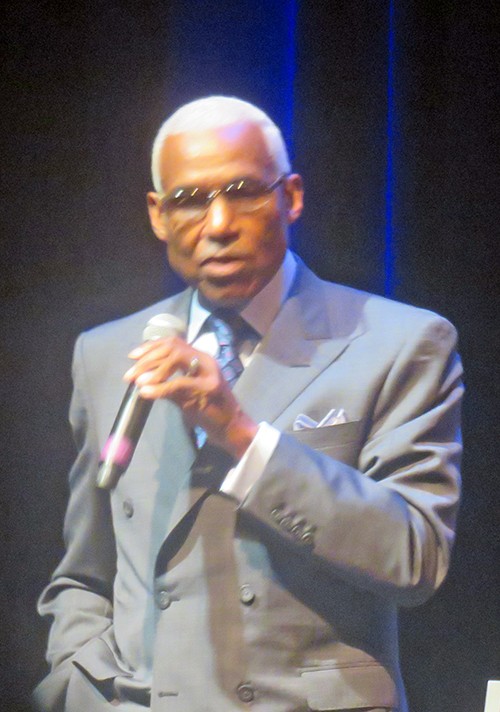

This latter concern is very much on the minds of the two other serious challengers for mayor — Councilman Harold Collins and Mike Williams, the president of the Memphis Police Association, on sabbatical for the duration of this election campaign. Both have made restoration of the lost benefits, in whole or in part, a centerpiece of their campaigns.

Collins and Williams also say they would pursue strategies on behalf of citizens trapped on the lower economic rungs, building prosperity from the ground up. Collins questions the value of what he calls the “$9 and $10” jobs resulting from the city’s current industrial recruitment policy and insists on a crash program to provide well-paid high-tech jobs to keep the city’s youth from seeking greener pastures.

Williams has talked of slowing the quest for big industry — and the tax abatements that go with it — long enough to upgrade city government’s core services, and to focus on helping smaller businesses survive. He has evolved his campaign from what many assumed would be a concentration on the lost-benefits issue alone into a wider-ranging consideration of matters like solar energy and a revamping of the city’s MATA bus service.

The challengers offer competing versions of change, and the mayor himself has focused on a revised urban future for Memphis — pitching to millennials and touting new parks and greenways and up-by-the-bootstraps programs and boasting of his ability to latch on to funding from outside the city, meanwhile promising more new and shiny treasures like the Bass Pro Pyramid.

In the course of their campaigns, these candidates have set forth four distinct and divergent pathways to the future.

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

ßL to R: Harold Collins, Jim Strickland, Sharon Webb, A C Wharton, and Mike Williams

There have been several mayoral debates this campaign year, most of them involving the core four — Wharton, Strickland, Collins, and Williams. Here, as one example of their approaches, are excerpts from their statements at a Sierra Club/League of Women Voters forum held on Monday night, one that focused entirely on environmental concerns.

(The quoted remarks are from their summations except that of Strickland, who had to leave early. His opening remarks are excerpted from instead.)

Strickland: “I’m running for Mayor because, in general, I want to clean up Memphis. … I have sponsored the volunteer code enforcement officer position [for individuals] to work with code officials and clean up their neighborhoods and other neighborhoods in the city. I have led the effort to create a grant program [to rehab] tax-dead properties. I want to work on a residential PILOT program, a tax incentive to help repopulate the inner city. We need to bring people into this city. We’re not growing in population; we’re not growing in jobs. I ask for your support.”

Collins: “The choice is really, really clear: [Will we be] a cleaner city, a better city? Is our transportation system antiquated or up-to-date? Blight has caused a decline in our population and increased apathy among our citizens and crime hotspots in our city. We should not continue down this road any longer. [We need] real choices, real change, a sense of urgency to deal with these problems. These are not election year problems. We have heard these now for six years, or maybe even 13 years.”

Williams: “We need a master development plan, and then we need to do smart development. … We need to tear down or repurpose certain properties in our city. … Since we are the 22nd largest city in the United States, we need a transportation system that is commensurate with that. To say that we’re going to stop developing or bringing in businesses to property that is available is nonsense. It’s time for new, innovative ideas.”

Wharton: “I’ve had the courage to stand up and lead in the face of tremendous opposition. I revived Shelby Farms Park. [There are] the bike lanes; everybody loves them now. … There are those who had questions about the conservancies, who now embrace conservancies. And I will do even more. We have to dream big, of bike lanes across the Mississippi River, along the levee, of bike lanes throughout our city, and programs to get the bikes for the children there, taking children all over the state to see our parks. They’ll come back here. That’s the vision I have for the city. Let me continue that.”

There they are in one brief snapshot: Strickland as technocrat; Collins as alarm-sounder; Williams as evolving planner; Wharton as self-styled futurist. All of them are rounder characters than that, of course, and one of them will guide us into the next age of Memphis. There are two more weeks to check them out, and we’ll doubtless have some more to say about them between now and October 8th.

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

Council races attracted more than the usual amount of attention this year. Here a crowd at Trinity United Methodist Church followed a debate involving seven candidates running for an open 5t6h District seat.

Meanwhile, here are summaries of the at-large City Council positions that will be resolved for sure on Election Day.

Super District 8, Position 1: This, like all the Super District contests, is winner-take-all, as a result of the 1991 ruling by the late federal Judge Jerry Turner that banned runoffs in at-large races — a category that, besides the mayor’s race and that for City Court Clerk, includes the two super-districts, each of which encompasses roughly half the city’s population.

Super District 8, predominantly African-American, encompasses the city’s western half, including the city’s inner-city core.

“In so many words or less,” as Position 1 incumbent Joe Brown would say, he should have easy going against unsung opponents George Thompson and Victoria E. Young,

Super District 8, Position 2: Janis Fullilove, notable for her firebrand advocacy of inner-city concerns, notorious for her penchant for getting into embarrassing scrapes, and somewhat beloved by (most of) her council mates for all that, is equally well-situated to prevail against opponents J. Eason and Isaac Wright.

Super District 8, Position 3: Now here’s a race — or at least a contest with the potential to be one. Mickell Lowery, son of the seat’s longtime possessor, the venerable Myron Lowery, has had abundant fund-raisers and significant shows of support resulting from them, and appears to be in good shape against opponents Jacqueline Camper and Martavius Jones.

Neither is a pushover, especially not Jones, who cut quite a figure as a pivotal member of the old Memphis School Board and was as responsible as anybody for the MCS charter surrender that led to the oh-so-temporary city/county school merger. But, once again, as with his near-loss last year to Reginald Milton in a County Commission race, Jones is running more or less on his own, without much money or a support network, as such.

Super District 9 basically encompasses the eastern part of the city and has a larger preponderance of white voters.

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

Super District 9, Position 3 seat, make their pitches to picnicking Democrats Steve Steffens (left) and Joe Weinberg.

Super District 9, Position 1: You can’t fault Robin Spielberger, who has been ubiquitous in her cost-conscious campaign for a council seat and has picked up any number of across-the-spectrum endorsements in the process. And you can say about as much for Charley Burch, the perpetually youthful federal air traffic officer who is also, like Spielberger, challenging the seemingly entrenched incumbent, Kemp Conrad.

Spielberger and Burch are so into it that their intensity has boiled over into an ongoing quarrel over the placement of their signs, with Burch claiming that Spielberger has uprooted a key sign of his and replaced it with hers. (She denies it, blaming an errant supporter.)

Conrad is seen by both of his challengers (and by supporters of CLERB, for his sponsorship of a delay in council consideration of the police-review agency) as a symbol of the establishment. Conrad, who has generous support from business interests, probably wouldn’t quarrel with that idea. His incumbency and a visibility sure to be enforced by sufficient advertising (which he can afford) in the campaign’s latter days give him a major edge.

Super District 9, Position 2: Who is Philip Spinosa? Between now and October 8th, you will have seen him — or images of him — on your TV set in well-produced commercials and, if you reside in the sprawling District 9 area, in your mailbox in equally well-produced mailers. Now that early voting has started, you have a fair chance of seeing him greeting arrivals at this or that polling place. (That’s if Spinosa follows the example of Reid Hedgepeth, who won election to the council in 2007 by following that formula.)

Where you probably won’t see the youthful FedEx sales executive, who — thanks to the generosity of the city’s business elite — has a massive campaign treasury, is in a public forum in a give-and-take situation alongside four rival candidates.

Each of those others has a story to tell. Pastor and former school board member Kenneth Whalum, a self-styled “gadfly,” is a declared foe of the status quo and an apostle for a newly configured municipal school district. He heads an informal “education slate” composed of council candidates in other races. Paul Shaffer, an official of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, has a working-class outlook and good name recognition in union circles and among democrats at large.

Stephanie Gatewood is another former school board member with a record of involvement in numerous causes. And Lynn Moss, a Cordovan, belongs to that stable of disaffected Memphians who are running hard for rank-and-file causes like restored employee benefits, saving the Mid-South Coliseum, and, in her case, for the right of de-annexation.

Spinosa’s financial edge, blue-ribbon sponsorship, and ongoing advertising blitz all give him an edge in a winner-take-all format. Although Moss gave him at least nominal opposition for the official Shelby County Republican endorsement, Spinosa also ended up claiming that credential.

Super District 9, Position 3: The aforementioned Hedgepeth has served on the council quietly and, in the judgment of many, effectively — faithfully representing the point of view of the business community, but suggesting development projects of his own and backing those of his colleagues, including those dear to the hearts of inner-city residents, like the Raleigh Springs Mall renovation.

Hedgepeth’s proudest moment came in 2012, when he broke his customary silence to make a powerful and probably decisive statement in favor of adding “sexual orientation” and “gender identity” to the language of the city’s workplace-protection ordinance. That action won him the endorsement this year of the Tennessee Equality Project, even though one of his two opponents, Zachary Ferguson, the director of Youth and Young Adult Ministries at St. John’s United Methodist Church, is openly gay.

The other candidate, Stephen Christian, a Nike employee, is, like Ferguson, a political newcomer whose horizons may be somewhat down the line.

The well-financed Hedgepeth, whose campaign signs rival those of Spinosa and Morgan in omnipresence, should finish well ahead.

City Court Clerk: This is another non-runoff race, and it would be strange indeed if Kay Spalding Robilio, who logged 30-odd years as a judge, first in City Court, then in Circuit Court, did not end up with a comfortable plurality.

Not that her opponents are slouches. What they amount to en masse is an unusually concentrated collection of African-American candidates with governmental experience or name recognition or, in most cases, both. And that’s the problem. There are so many of them that they will inevitably slice up and splinter each other’s vote totals (such is the demographic fact of life, like it or not), leaving Robilio, a white female still well-regarded and liked in the community at large, well in the lead.

Robilio was basically pressured to resign her Circuit Court judgeship in 2013 at a time when she was charged with misconduct by a state ethics board for personally investigating facts pertaining to a child custody case in her court. The reality is that, while such a breach of the canon might — and did — appear serious within the legal community, it is not the sort of offense likely to seem especially scandalous to a lay public.

Meanwhile, several of Robilio’s opponents have had their own bumps in the road. But, again, their main drawback as aspirants for the clerkship is that they will seriously reduce each other’s vote totals. For the record, they include: County Commissioner Justin Ford; current councilwoman and former school board member Wanda Halbert; and former councilman and Juvenile Court Clerk, Shep Wilbun.

In addition, Thomas Long II bears a name so close to that of his father, the outgoing clerk, as to be seriously confusing, and William Chism Jr.‘s last name will remind voters of former county commisioner and interim state Senator Sidney Chism, who still remains a political broker of note. Antonio Harris, a longtime employee of the clerk’s office, can tout his experience there, unique in the field.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Toby Sells

Toby Sells  Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker  Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker  Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker  Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker  JB

JB

JB

JB  JB

JB

Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker  Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker