“You picked up on this energy

I can see it in your E-Y-E

It’s like I’m fresh off the shelf, fresh off the lot, fresh out the pot.

It’s like I’m brand new … “

Cameron Bethany wrote and sang those words at a turning point in his life, when he was indeed feeling brand new. For the singer/songwriter and his colleagues in the Unapologetic collective, it marked one of those moments of reinvention that they all strive for, a moment of pure authenticity, unaffected by conventional demands. Like most such moments, it was intensely personal.

Darnell Henderson II

Darnell Henderson II

Cameron Bethany

That was more than three years ago, released on his debut album, YOUMAKEMENERVOUS, so it came as a bit of a surprise when that musical moment took on a new life this summer. In the Netflix series Trinkets, as one character confronts two others and then walks out of the scene in disgust, the track’s beats kick in, full of portent and tension, until the final credits and the song’s chorus roll out together.

It feels as if the music was designed for the scene. And while the licensing of his song for a major television series, known in the industry as placement, represented a hefty payday for Bethany and co-producers Kid Maestro and IMAKEMADBEATS, it was the way the show’s and the song’s aesthetics dovetailed that made it feel like such a triumph to the singer.

“When we were making the record, when I first brought it in, I had a small GarageBand track, and we talked about what I did as we remade it. We all agreed that it sounded like something that could be used in movies or commercials,” Bethany tells me. “But I couldn’t imagine it might be placed. So it’s almost like we predicted the future a little bit. Still, it ended up being better than anything I could have thought about.”

Although having music tracks placed in movies, television, and commercials is part of Unapologetic’s bread and butter, all agree that this moment was special. “When I first heard that [the placement] was happening, I went back and ended up falling in love with the show,” Bethany says. “Which I was hoping for. I was hoping it was something I could watch on a daily basis, something I gravitated to. Me liking it made me love that moment and made that moment so much more. I would have been grateful either way, whether I liked it or not. But it adds something, to be a fan of something that your work is featured in.”

It doesn’t always happen that way, of course, but placing a song in a movie, a series, or an ad, or scoring such media from scratch, can often be the one time an artist or group is paid a fair price for their music. Now, with live shows few and far between due to the pandemic, and streaming paying only pennies for plays, such placements, also called synchronization or “sync”-ing, have taken on a new importance.

David Patten Mason

David Patten Mason

Marco Pavé

Memphis rapper Marco Pavé, who has also enjoyed some success with music placements, including the locally made indie film Uncorked, notes that there are different levels of success in the game, but all of them tend to be more lucrative than live shows or album sales, at least for an independent artist. And they tend to offer more exposure as well.

“The placements that you’re really trying to get are the feature films in theaters,” he says. “TV is more of a mid-tier, that could be more high-tier depending on the network. That could range from $2,500 to $5,000 for one song. So it’s definitely a payday for a lot of artists. And it’s a huge discovery tool. A lot of people consider music supervisors to be the new A&R of the music industry. It’s a level of discovery that you really can’t beat because for one, you’re getting paid, but also you’re getting discovered in a way that labels are not suited to do.”

If music supervisors, in choosing the tracks that films and series use, are especially hands-on, they may indeed take on the de facto role of artist and repertoire (A&R) development. But just as often, tracks are lifted wholesale from albums or singles.

That’s been the case for a long time. One local example comes from the surf/crime jazz group Impala, whose love of such genres led them to self-release an EP cut at Easley-McCain studios in the early ’90s.

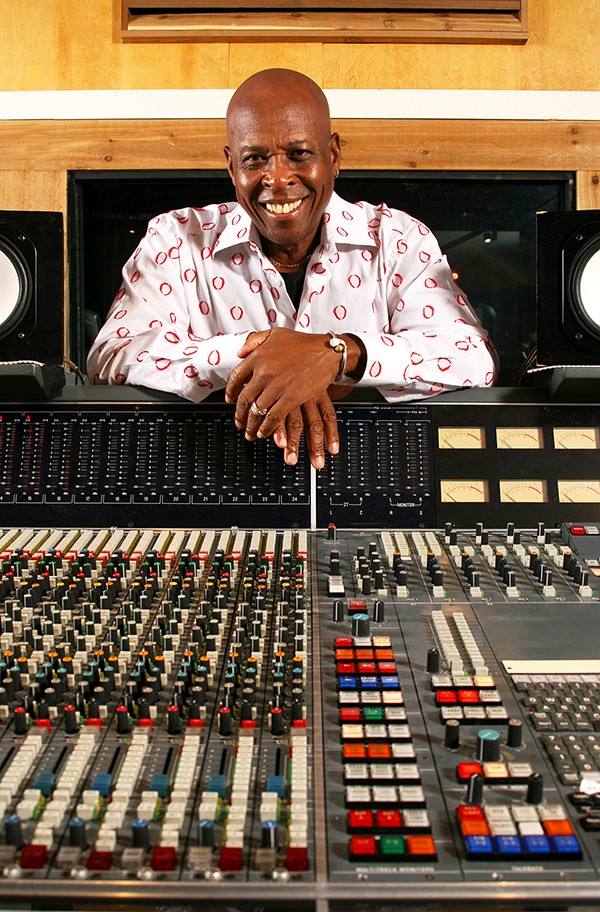

Billy Fox

Billy Fox

Joe Restivo, Willie Hall, Lester Snell, and Michael Tolesore

Bassist and producer Scott Bomar recalls that the EP led to bigger things. “Then we put our first record on Estrus Records, Kings of the Strip, and that got distributed real widely. It seemed to get a lot of attention specifically in Los Angeles. That was the days of faxes, so I remember getting a fax out of nowhere from somebody at HBO, and they wanted to license a song for a Rich Hall show. Which we did. I didn’t know anything about licensing whatsoever. We’d been working in the studio with Roland Janes, so I asked Roland about it and he broke it down and explained the business part of it. And the information he gave me, I feel like I made a whole career out of it. He really gave me some good advice.”

The best was yet to come for Impala, thanks in part to serendipity. “The story that I heard is that George Clooney’s music supervisor for Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, David Arnold, was in New Orleans for Jazz Fest and he bought our very first EP at a record store there. It had our version of Henry Mancini’s ‘Experiment in Terror.’ And we licensed that to George Clooney’s first film that he directed. It was probably the biggest placement we had.”

That such an obscure track could translate into a major placement many years after its release leads Bomar to conclude: “The best thing you can do to get your music licensed is tour and try to get airplay. The more exposure you get for your music, the more chance you have of a director or somebody hearing it. Of course, you can send the stuff to people, but it seems like as much as you try to get things licensed, a lot of times it’s just sort of blind luck. Random.”

It’s ironic that Bomar emphasizes the role of luck and fate, when in fact he has parlayed those early successes with Impala into a career in the ultimate “placement” — soundtrack production. Early work by the band first caught the attention of local underground auteur Mike McCarthy, who hired them to score his film Teenage Tupelo (remastered and reissued this year). This in turn caught the ear of then-burgeoning filmmaker Craig Brewer, who, after his The Poor & Hungry captivated filmgoers, contacted Bomar about his next project, a film called Hustle & Flow.

“He gave me a script for it,” Bomar recalls, “but it took another five years for it to actually get made. And when John Singleton came on board, he said I’ve got some great composers in Hollywood that could do this, but Craig really vouched for me. But, even though I’d been working with Craig on this thing for five years, he said to me, ‘You’re gonna have to sell John.’

“Now, Shaft was John’s favorite movie in the whole world. His email even had Shaft in the name. So I told him about [Bomar’s soul band] the Bo-Keys, with Willie Hall, and Skip Pitts who played with Isaac, and he got real excited about that. And then I realized I had a live recording from the night before in my pocket. So I put the CD in and the first thing on there was us doing the theme from Shaft. The first thing he heard was Skip doing that wah-wah guitar intro and Willie playing the high hat, and he said ‘Yep, this is it!'”

That 2005 soundtrack by Bomar, which complemented the pure hip-hop that won Three 6 Mafia an Oscar for the film, would take on a second life this year, as Brewer worked on another labor of love, Dolemite Is My Name. “Craig and Billy Fox were editing the film and trying out different music and having a hard time finding the right vibe,” says Bomar. “And Craig told Billy, ‘Put in the Hustle & Flow score.’ Craig said once they started editing with that score, it really started to come together. I think they really fell in love with that sound for Dolemite.”

The final result was a masterful, original genre study of blaxploitation scores in what may be Bomar’s finest achievement. Yet he still finds soundtrack work and placements to be elusive. “If that was the only thing I did, it wouldn’t be sustainable for me,” he says. “I’m thankful for those projects when they come around, but they’re not always there. For someone outside of Hollywood to get placements, it’s a little tricky. You’re not gonna get as much of it. You’re not in the middle of all the action.”

Though both Bomar and the Unapologetic artists have stoked interest in placements with frequent visits to New York and Los Angeles, an alternative approach, being pioneered by Made in Memphis Entertainment (MIME), is to bring L.A. to Memphis. With the legendary former Stax songwriter David Porter as a partner, MIME can turn some heads, but that’s also due to astute management by company president Tony Alexander.

“About two and half years ago,” explains Alexander, “as part of our overall strategy, we acquired a songs catalog, a sync business in L.A. called Heavy Hitters Music Group, that had been around about 25 years. And that business has continued to grow. So that’s our L.A. operation, and that has been very, very beneficial to us. Made in Memphis Entertainment has the label, but we also have the recording studios, the publishing companies, and our distribution business. Heavy Hitters Music Group is one of our publishing companies. They represent about 1,700 artists, and their business model, unlike many that sign the writer, is to sign the songs. And then they represent the songs for placement. They have a pretty amazing track record.”

While MIME develops local performing artists like Brandon Lewis, Porcelan, and Jessica Ray, they also quietly go about the business of placements. And yet, Alexander notes, “The vast majority of who we represent are not local to Memphis.” Rather, Heavy Hitters Music Group tends to work with L.A.-based producers, who are more savvy to the ways of placed recordings. Accordingly, one of MIME’s missions has been to educate local creators in the ways of placed tracks.

“One of the reasons why education is such an important component of what we do is that we wanted the local artists here in Memphis to understand what makes songs sync-able,” Alexander says. “These are the things that make them easy to clear. So we can create more opportunities for Memphis artists. Because historically, most of the time that Memphis artists were able to get placements, it was for things that were either produced here or had a Memphis theme. It was not access to global projects or projects that were not Memphis-oriented. And that’s what we’re really trying to do, is open up opportunities for Memphis artists to get placements in non-Memphis-oriented projects.”

As the manager of MIME’s 4U Recording Studio, Crystal Carpenter takes that educational role very seriously, showing artists who work there, for example, how important documentation, credits, and even file formats are. As Alexander explains, “One of the things that makes sync easier for an artist or writer is if it’s one stop. If the master and the publishing is controlled by the same individual, that’s really what a lot of music supervisors are looking for. Because if it’s too complicated, they’ll just move on to another song.”

Beyond impromptu teachable moments in the studio, MIME also sponsors workshops to confront such issues in a more focused way. Tuesday, October 20th, and on the 27th, they’ll host workshops covering “the nuts and bolts of music licensing and publishing, creating and pitching, artist branding and sync-writing for a brief vs. placing existing music.”

MIME is not alone in this pursuit. The local nonprofit On Location: Memphis was originally formed to produce the International Film and Music Festivals, but when entertainment attorney Angela Green took over, she changed directions. “I felt that the film screening space was getting crowded, and that there were a lot of organizations doing it quite well. There were other areas of film and music being overlooked. That’s what led to me coming up with the Memphis Music Banq.”

Margaret Deloach

Margaret Deloach

Memphis Music Banq

The Memphis Music Banq, launched a year ago, administers music for placements, and now represents the work of nearly a dozen local artists. This Banq contains songs, not dollars, though its aim is to translate one into the other, and it offers workshops and networking opportunities for artists who seek knowledge about the world of placements. One lighthearted series they host is their “Mixer Competition,” wherein two or more music producers try scoring a single film, and viewers vote on the best score. Such opportunities for education and networking have already paid off, with Memphis Music Banq creator Kirk Smith having landed a soundtrack deal for Come to Africa, to be screened at this year’s Indie Memphis Film Festival. (The next such mixers are scheduled for October 15th and October 20th.)

And yet, with many of these educational opportunities focused on how to do things according to the established norms and expectations, it’s important to remember the fundamental philosophy of IMAKEMADBEATS, founder of Unapologetic: Be your most authentic, vulnerable self in all your work. “I feel like if people are looking for a hired hand, they’re not going to come to me,” he says. “They’re gonna come to me for what I do. They’re gonna come to Unapologetic for what we do. Because we’re daring and we’re bold. It would be hard to imagine someone saying, ‘Hey Cameron, we need you to do this Aretha Franklin thing here. Make that happen.’ We’d be like, ‘What?’ People are going to go to Cameron because he’s going to be who he is.”

Courtesy David Porter

Courtesy David Porter  Darnell Henderson II

Darnell Henderson II  David Patten Mason

David Patten Mason  Billy Fox

Billy Fox  Margaret Deloach

Margaret Deloach