Ryan Coogler has proven himself to be one of the great masters of genre films. Every time he’s tried a new kind of film, he has mastered it and made it better. In 2015, he made the Rocky spin-off Creed, starring his friend and frequent collaborator Michael B. Jordan as the son of Rocky’s frenemy Apollo Creed. It was, incredibly, better received than Sylvester Stallone’s attempt to revitalize the inspirational sports picture he had pioneered. Remember 2005’s Rocky Balboa? Of course you don’t.

Then Coogler moved on to the superhero space with Black Panther, the consensus choice for the best chapter of the never-ending Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU). Coogler saw the potential of his star Chadwick Boseman to transcend the shallow and banal crash-bang and become a hero for the people. And I’m not just talking about Black people, who were finally able to see on-screen both a hero and a culture which looked like them. T’Challa was the MCU’s moral center, the person who took time to wrestle with the right and wrongs of the situation, rather than just punching the bad guys. Marvel’s vision of good leadership is not the American President Thaddeus Ross, a barely reformed war criminal, or Tony Stark, the technocratic billionaire. It’s T’Challa, the King of Wakanda, who prioritizes justice for all humanity and puts his nation’s (and his own) blood and treasure on the line to achieve it.

Now, Coogler ventures into the horror genre with Sinners. The 21st-century superhero film cannibalizes genres so they can be digested by the corporate body. Captain America: Winter Soldier was a ’70s paranoid thriller in colorful tights; Guardians of the Galaxy is a sci-fi adventure with the occasional super-heroic flourish. Even Black Panther more closely resembled The Adventures of Robin Hood than it did Thor: The Dark World. The horror genre gives its practitioners more freedom. Throw in an atmosphere of creeping dread, a few jump scares, and a little monstrosity, and you can call it horror. After all, this is a genre that encompasses both David Lynch’s Fire Walk With Me and Attack of the Killer Tomatoes.

Coogler takes the opportunity to play fast and loose in Sinners, bringing in elements from all over the cinematic map. One of its biggest influences is Craig Brewer’s Black Snake Moan, a decidedly not-horror psychological portrait of two deeply damaged people trying to find themselves in the squalor of North Mississippi. Another major tributary is Kathryn Bigelow’s Near Dark, the vampire neo-Western that provided Bill Paxton’s finest hour. If I had to pin it down, I would call Sinners folk horror. Like The Wicker Man and Midsommar, it finds terror in the inscrutable laws of pre-Christian pagan beliefs.

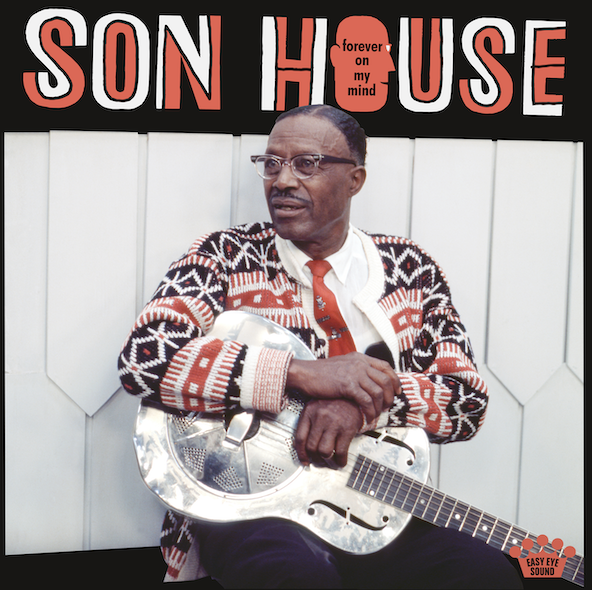

The film’s animated preamble introduces us to the concept, handed down over millennia through dozens of different cultures, of shamanistic figures whose music-making was so powerful that it became magic and temporarily tore the veil between our world and the spirit world. We then meet Sammie Moore (Miles Caton). It’s October 1932 in Clarksdale, Mississippi, and times are tough. Sammie’s a preacher’s son who quotes scripture from the pulpit on Sunday morning after playing the blues on Charley Patton’s resonator guitar on Saturday night.

Against the wishes of his pa, who warns him against “playing music for drunkards who shirk their responsibilities,” Sammie takes a gig at the Delta’s newest venue, Club Duke. The owners are the Smokestack twins, Smoke and Stack, both played by Jordan. They left Clarksdale 15 years earlier to fight in World War I, then joined the Great Migration to Chicago, where they became enforcers for Al Capone’s Prohibition smuggling operation. After years of being good soldiers, they have unexpectedly returned to the Delta, throwing cash around and sitting on enough bootleg booze to stock a juke joint for months. How they came into this good fortune is one of the film’s early mysteries.

The twins buy a former cotton warehouse and proceed to get the band back together, Blues Brothers-style. Along with Sammie, they recruit piano pounder Delta Slim (the great Delroy Lindo) and the singer Pearline (Jayme Lawson) for opening night. It is one hell of a party. Every drunken shirker in a three-county radius packs into the run-down old building to party their butts off late into the night.

Did I mention that Sinners is also kind of a musical? And that some of the music was recorded here in Memphis by Boo Mitchell at Royal Studios? Coogler frames the big emotional moments with musical numbers performed by his cast. On Club Duke’s opening night, Sammie’s songs whip the revelers into a frenzy of ecstatic dancing. When people from other eras start to appear in the barn, from a masked San shaman of Kalahari to Eddie Hazel decked out in Parliament-Funkadelic-era Afro and star-shaped sunglasses, we know we’re through the looking glass.

The revelers are mostly oblivious, but someone notices the magic working. Remmick (Jack O’Connell) appears, smoldering from the sunlight. He’s an Irishman of indeterminate age, who knows all the old Appalachian folk songs. When he and his little band show up at Club Duke, the door man Cornbread (Omar Benson Miller) won’t let them in. Annie (Wunmi Mosaku), Smoke’s ex-wife, is a secret voodoo priestess who recognizes the undead when she sees them. But it’s going to take more than a mojo bag and a trunk full of guns to defeat the devils this time.

Sinners spends a long time giving backstory to its sprawling cast, so that when the action kicks in, we feel each loss and setback. Coogler takes big swings, but not all of them connect. Jordan’s double duty as twins could have been a disaster, but he pulls it off with bravado. On the other hand, a half-assed subplot involving the Klan bogs things down in the final reel. It hardly matters. Sinners is one of our great filmmakers exploring the outer limits of his gifts. Let Coogler cook.

Sinners

Now playing

Multiple locations