Last week’s storm affected Mississippi River towns differently, ranging from a mass rescue in West Memphis to “nothing happened at all” in Caruthersville, Missouri. The total damage, however, could cost $90 billion, according to one weather company.

The relentless bouts of severe weather began with tornado warnings on Wednesday, April 2nd. Lines of high wind threatened the Mid-South Thursday through Saturday. The storm finally moved on Sunday but not before dumping nearly 12 inches of rain in Memphis.

The storm fronts were wide, of course, and did not affect towns the same way. Mayors of towns up and down the Mississippi River gave highlights of their challenges and lucky misses during a news conference Monday by the Mississippi River Mayors Cities and Towns Initiative.

Memphis Mayor Paul Young said “the last few days have been a challenge.” He said the city had “historic levels of rainfall,” which created more than 600 tickets to the city’s 311 system. Also, wind and rain felled 109 trees that blocked roads, Young said. Traffic lights at intersections went out, too, and the massive amounts of water were a challenge for the city’s drainage system, he said.

“Thankfully, our teams worked really hard and they were very responsive and very prepared for the storms that took place,” Young said.

Across the river in West Memphis, teams in boats rescued nearly 100 people caught in the floodwaters created by nearly 13 inches of rain.

However, up the river in Alton, Illinois, Mayor David Goins said, “we’re doing fine.”

“I believe we dodged a bullet because most of the rain was south of us,” Goins said, noting Alton got between 3 inches to 5 inches of rain.

In Cape Girardeau, Missouri, though, limbs and trees were down all over town, said Mayor Stacy Kinder. Downtown buildings suffered roof and facade damage and blown-out windows. Flash flooding backed up sewage and water into basements in homes across town. In a typical few days, the city’s waste water treatment plant treats about 26 million gallons of water, Mayor Kinder said. Between April 2nd and 6th, the system treated 91 million gallons of water, she said.

Caruthersville, Missouri, Mayor Sue Grantham said “we got really lucky. The dear Lord was with us; we don’t have any flooding around us except at the river,” Grantham said. “Nothing happened at all. I did see one small car in a ditch. But by the time I got back around, it was gone.”

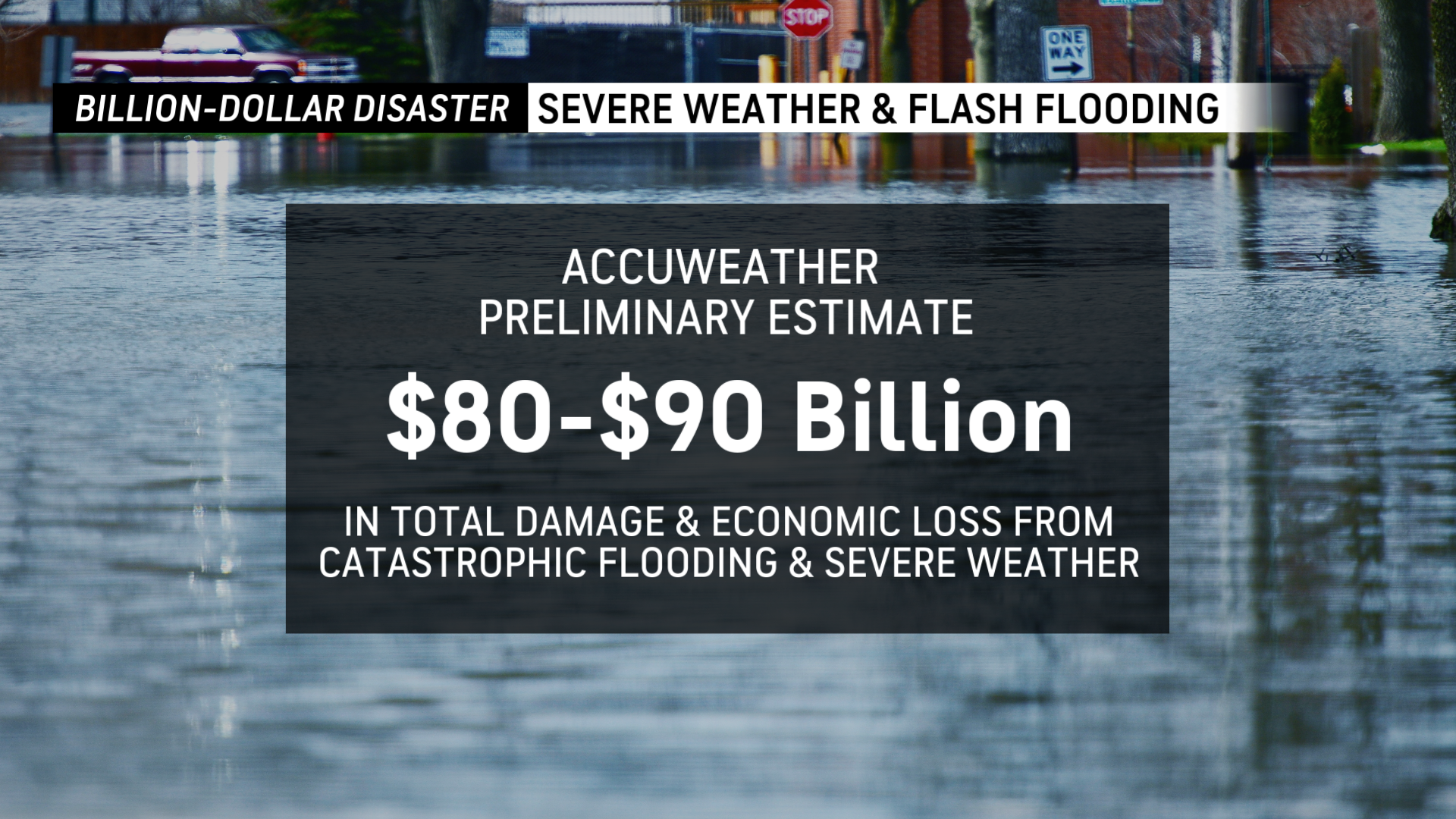

Experts at AccuWeather, a weather media company, projected Monday morning that the storm caused an estimated $80 billion to $90 billion in total damage and economic loss.

”We’re heartbroken by the loss of life and destruction from this once-in-a-generation storm,” said AccuWeather Chief Meteorologist Jonathan Porter. “ Houses and businesses were destroyed by tornadoes. Homes and vehicles were swept away by fast-moving floodwaters. Bridges and roadways were washed out or destroyed in some areas. Travel, commerce and business operations were significantly disrupted. It will take years for some of the hardest-hit communities to recover.”

Memphis Mayor Young said his team is watching the Mississippi River now, though. The river is expected to peak here on April 14 at about 37 feet.

“For us, flood level is about 34 feet,” he said. “We do think we have enough things in place to manage [flooding] at that level, however. It is something that we’re going to be paying attention to.”

David Welsh, a senior hydrologist with the National Weather Service, said he anticipates a “long, broad crest” on the Mississippi that could last for up to two weeks. However, no rain fall is yet predicted for the next week, which might give the river a little bit of time to start coming down.

Mississippi River Cities & Towns Initiative

Mississippi River Cities & Towns Initiative  Mississippi River Cities & Towns Initiative

Mississippi River Cities & Towns Initiative  Mississippi River Cities & Towns Initiative

Mississippi River Cities & Towns Initiative  Mississippi River Cities & Towns Initiative

Mississippi River Cities & Towns Initiative  Mississippi River Cities & Towns Initiative

Mississippi River Cities & Towns Initiative  Mississippi River Cities & Towns Initiative

Mississippi River Cities & Towns Initiative