Every school day, I pick up my two kids. I walk to the door of my youngest’s elementary school and we walk back to the car. We drive to pick up the oldest and head home, talking about their respective days.

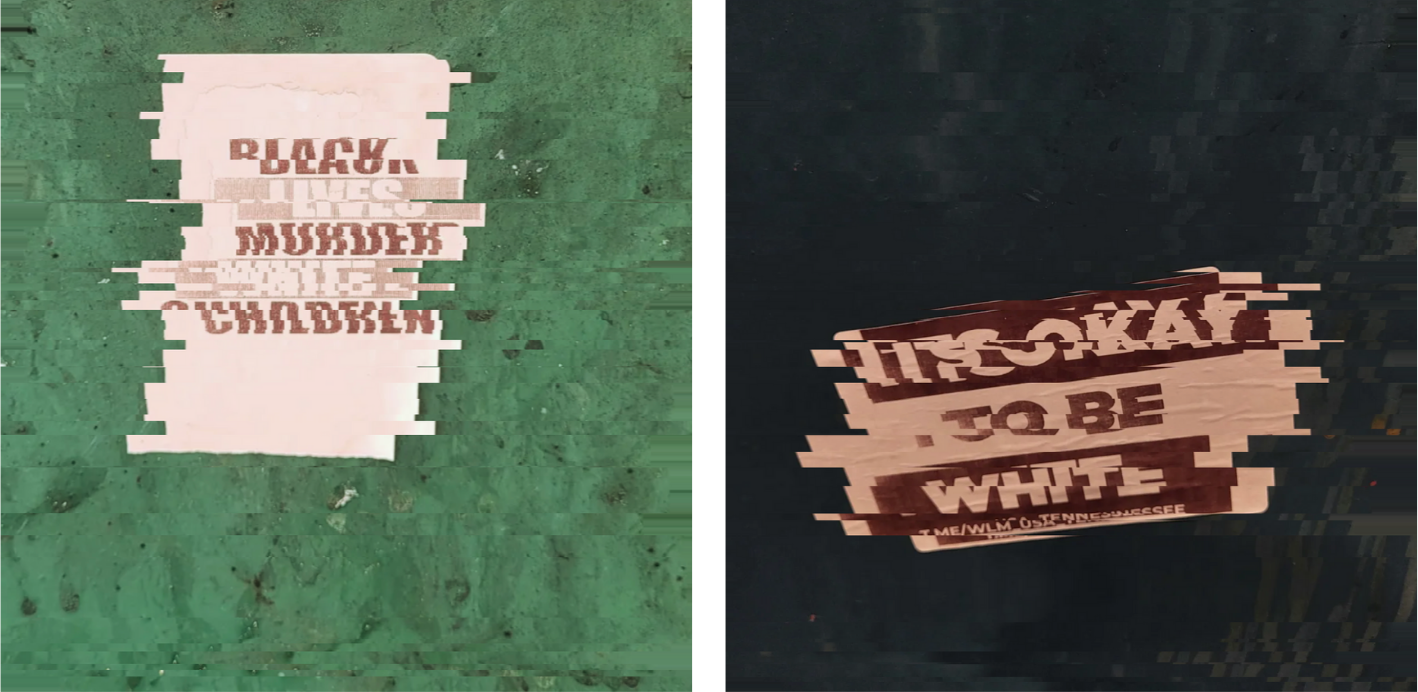

Recently, though, I was late picking up the oldest because someone decided to add stickers to the dumpsters where my youngest has to pass to get to my car. In big black and white letters, one read: IT’S OK TO BE WHITE and another said: BLACK LIVES MURDER WHITE CHILDREN.

I couldn’t help but say, “OH WHAT THE F—” out loud and then I told my youngest kid to wait. But he jumped right in, and together, we scraped off four of the former and two of the latter. I cussed and sweated as we worked, and I told my son we had to get them off before anyone else saw what these *expletive deleted* put near his school.

We took an example of each into the office to tell the nice lady who calls us adults Mom and Dad but knows all the kids’ names that a white supremacist group had been through. I tried to keep it businesslike, suggesting that the maintenance staff keep an eye out in case there were more.

But the truth is that I also spoke in that grown-up tone because a second-grader was in the office and I didn’t want him to be curious and ask what I’d given the nice lady.

In 2022, nearly 70 years after Brown v. Board of education, I had to hand a Black woman, who cares deeply for children, hateful propaganda. We both tried to pretend it was regular vandalism. Neither of us wanted the child to know he was being threatened.

She murmured, “Oh my God, why would anyone do this?”

Why indeed?

I live in Rozelle-Annesdale, where I frequently see Black Lives Matter yard signs on our street. Our neighborhood is next to Cooper-Young, where the city’s LGBT community center sits and where every other yard has a BLM sign and several houses have large artistic pieces supporting BLM.

Reports of these stickers keep popping up on social media in the Cooper-Young district. Presumably, the area is being targeted for being whatever “woke” means to racists. Funny how closely linked are the dual rages at a rainbow crosswalk and Black Lives Matter. It’s almost like the anger isn’t logical.

I see you people. I grew up in West Memphis and Marion, across the river in Arkansas, back when it was still very segregated. I recognize the code words. The sly jokes meant to obscure anti-Black feelings. The small disrespects done to Black people. You’re angry that you’re not kings and need to blame someone. So, of course, you do the most radical thing you can think of — you put stickers on a dumpster for 7-year-olds to read. That will show them.

This isn’t the first time. In January, at my middle schooler’s campus, about a dozen “IT’S OK TO BE WHITE” stickers showed up on the fence posts; then earlier this month, another few appeared on the backs of signs. My youngest thought I was insane when I parked and jumped out of the car to claw them off. When I took an intact sticker to the faculty, I leaned in to assert, “This is absolutely a white supremacist slogan. They have been all around the area.”

I wanted to be sure the staff didn’t presume that maybe it was some musical band sticker or a TikTok challenge by kids trying to be edgy. I couldn’t let this slip into that space where people convince themselves that what they’re seeing may not be what they think it is. I wanted to pull the alarm as hard as I could. I didn’t want to scare the faculty, but I wanted them to take it seriously. No child deserves to start their school day in racial violence.

Memphis-Shelby County Schools serve a 74% Black student body in a 64% Black city and a 54% Black county. If you have a kid in MSCS, you know that the educators and staff have absolutely stepped up at every opportunity to provide a safe place for the kids. They’ve twisted themselves in knots to focus on getting young people what they need, whether it’s virtual science demonstrations via Microsoft Teams or shoes that don’t pinch. During learning from home because of the pandemic, meals were provided, devices were distributed. There was even a number to call for parents to be tutored so we could support our kids with homework help. My seventh- and fifth-grader have been cared for in ways I never knew a public school could provide. In times when it felt like the entire country went insane, I turned to school superintendent Dr. Joris Ray in his press conferences. MSCS is an incredible boon to the children lucky enough to attend.

Children should be protected. The mom in me cannot ever understand how anyone could hurt a child. We don’t value a baby because they’re “diverse”, we value them because they are a BABY. (My Southerness means all people under voting age are babies, but babies can include anyone younger than me, anyone who needs protection.) Black kids don’t need to earn our protection by being relatable. They’re just babies.

All kids are sweet and weird and a pain in the butt and eat all the damn cookies when you aren’t looking. There’s nothing they have to do to deserve our care. There’s nothing they can do to lose it.

Standing near the stink of an elementary school dumpster (rotten honeybuns and hot milk are a MIX, let me tell you), scraping off white supremacist propaganda, all I could think was that a person like this – someone who saw the need to put a child in their place, to establish dominance over a kid who has enough on their plate just learning to tie their shoes and remember that I comes before E but not all the time – should not be given any consideration. What kind of foul coward slips in the dark of night to proclaim something akin to the 14 words? What manner of bully has to threaten a small, powerless human being with anonymous words?

It made me laugh when I ranted and raved back at home to my husband, as I was cleaning adhesive from my fingernails, that this was basically, “You will not replace us” in some really weak inkjet formatting. I was tearful and angry.

What made me laugh is that they will replace us. The kids, that is. This world will be theirs. My fellow mayo moms and ranch dressing dads and provolone parents have a choice. Every single time we uncomfortably chuckle at a racist joke or walk past a sticker insisting that asking for rights is akin to murder, we are complicit. I probably can’t tell the people that cranked these stickers out on address labels with their Canon home inkjets anything. They’re too far gone to be reasoned with.

I can tell you that taking a moment to scrape off a sticker full of hate will tell your kid all they need to know. We may not be able to do big things. We can’t change a racist system all at once. But when we come across something vile and harmful, we do have a choice.

We can scoff and say, “Oh that’s terrible,” or we can teach our kids to take ‘em down.

Katrina Coleman is a parent of two and a comedian. They produced the Memphis Comedy Festival as well as the You Look Like show.

This story is brought to you by MLK50: Justice Through Journalism, a nonprofit newsroom focused on poverty, power and policy in Memphis. Support independent journalism by making a tax-deductible donation today. MLK50 is also supported by these generous donors.