In 1998, Kelly Chandler, a University of Memphis film student, got some of her fellow budding filmmakers together at a coffee shop in Midtown. Frustrated that there was no place to show their work, they decided to take matters into their own hands. The ad hoc film society attracted the attention of James Patterson’s arts philanthropy, Delta Axis, which took over running what would soon come to be called the Indie Memphis Film Festival.

Twenty years later, it’s a big birthday for Indie Memphis.

The first year, about 40 people attended the festival. In 2016, that number was more than 11,000. Indie Memphis Executive Director Ryan Watt says that even though the festival began as a niche event for filmmakers, it now ranks among the city’s most important cultural events.

“We’re bringing people to Memphis every year who would not be coming to Memphis otherwise — filmmakers, storytellers, journalists, and industry people who come from L.A. and New York,” Watt says. “They are people who tell stories about us when they go home. So for us to be in the conversation nationally, internationally in the film world is important.”

But the most important element is the audience, which is overwhelmingly from Memphis and the Mid-South area. Indie Memphis’ mission is to offer Mid-South audiences experiences they won’t get anywhere else. It’s what has kept the festival going at a time when other regional festivals are vanishing. It’s why Watt and company have plans to use the 20th edition of Indie Memphis to thank the people of the Bluff City.

When the festival invades Overton Square on Friday, November 3rd, it will kick off a three-day block party. Cooper between Union and Monroe will be closed and a giant tent erected. The space is a nexus between three of the festival’s weekend venues — Playhouse on the Square, Circuit Playhouse, and the Hattiloo Theatre. Equipped with a portable outdoor screen, the tent will not only be a gathering place for the audience, it will become a venue itself.

On Friday night, it will host the music video competition, where bands and directors from all over the world will present their latest works, followed by a special screening of Thank You, Friends: Big Star’s Third Live … And More. The documentary is a record of the night musicians from all over the globe came together to pay tribute to the legacy of Alex Chilton and the band of Memphis misfits who grew from obscurity into one of the most influential acts in rock history. The free screening will be hosted by Big Star drummer and Ardent Studios executive Jody Stephens.

Saturday night, the official 20th anniversary celebration street party, featuring DJ Alex Turley and “visual treats on the outdoor big screen,” will rage until midnight.

Here’s a look at some of the highlights to catch at the 2017 Indie Memphis Film Festival. Thom Pain

Two days before the festival moves to Overton Square, it will open on Wednesday, November 1st with a gala red carpet show at The Orpheum Theatre’s Halloran Centre. The opening night film is Thom Pain, starring Rainn Wilson, who became internationally famous during his eight-year run as Dwight Schrute on The Office, the wildly successful NBC comedy. The film, which was adapted from the Pulitzer Prize-nominated play, Thom Pain (based on nothing) by Will Eno, is basically a one-man show, in which the lead character’s rambling comic monolog reveals deep truths about himself and life itself.

The play has been translated into more than a dozen languages and is regularly performed around the world. This adaptation was recorded during Wilson’s starring run at Los Angeles’ Geffen Playhouse and will make its world premiere at Indie Memphis.

Wilson, Eno, director Oliver Butler, and producer Gil Cates will all be in attendance for a Q&A after the screening. New York Times reviewer Charles Isherwood said Thom Pain “can leave you both breathless with exhilaration and, depending on your sensitivity to meditations on the bleak and beautiful mysteries of human experience, in a puddle of tears.”

You Look Like

You Look Like

Back in May, The Memphis Flyer‘s Chris Davis reported on You Look Like, a made-in-Memphis comedy phenomenon created by Katrina Coleman and Tommy Oler.

“I had gone to see it and was really inspired by it, so I got local filmmakers to make a show,” says Craig Brewer. “Sarah Fleming was in charge of shooting it. Edward Valibus was in charge of cutting it together. We made a sizzle reel, and then we took that sizzle reel and sold the concept to [independent studio] Gunpowder and Sky.”

With the backing of a national production company, Brewer’s BR2 Productions, led by producer Erin Hagee Freeman, created 10 10-minute episodes of the most radical game show you are likely to see. Two comedians face each other on the P&H’s tiny stage and trade insults. The only rule is each line must start with the phrase “You look like …”

It’s no-holds-barred shade throwing, but despite all the wildly offensive vitriol, the mood is convivial. “It was very important for us to capture the atmosphere we felt at the P&H Cafe. You felt very safe to laugh,” says Brewer. “It just felt inspiring. It didn’t feel insulting. That was the key thing we had to figure out about the show. How do we capture that feeling in that live audience?”

This will be the world debut of the show, which will screen four episodes. You Look Like is in turns shocking and side splitting. An audience applause meter determines the winners, but some of the best moments take place in the heavily graffitied bathroom of the P&H, where comedians who lose the duel of wits are forced to stare into the Mirror of Shame and insult themselves.

Producer and editor Valibus was responsible for cutting down the hours of filmed material into a coherent, fast-paced contest. “The closest comparison is a roast battle, but they usually tell about three jokes per comedian. That’s a bazooka. We’re more like a machine gun. … I think what’s really funny is watching a comedian take a hit. Sometimes they’ll be like, ‘Yeah, that’s pretty true. That’s spot on.'”

Valibus says the edgy humor is ultimately empowering. “I think it’s because everybody gets theirs. There’s self-depreciation in just being attacked. It’s finding that we’re all screwed up. It’s nice that someone took the time to find out what’s screwed up about you.”

King

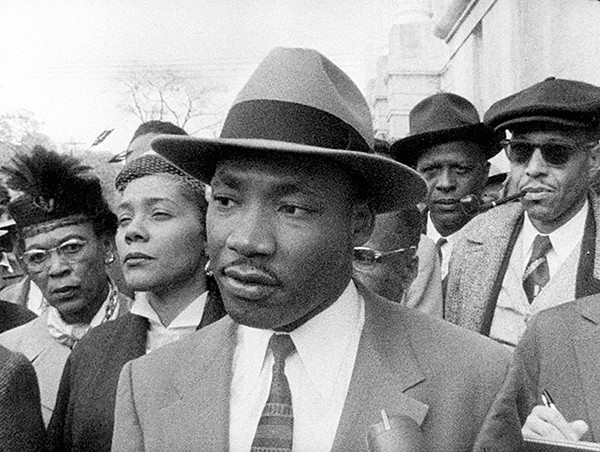

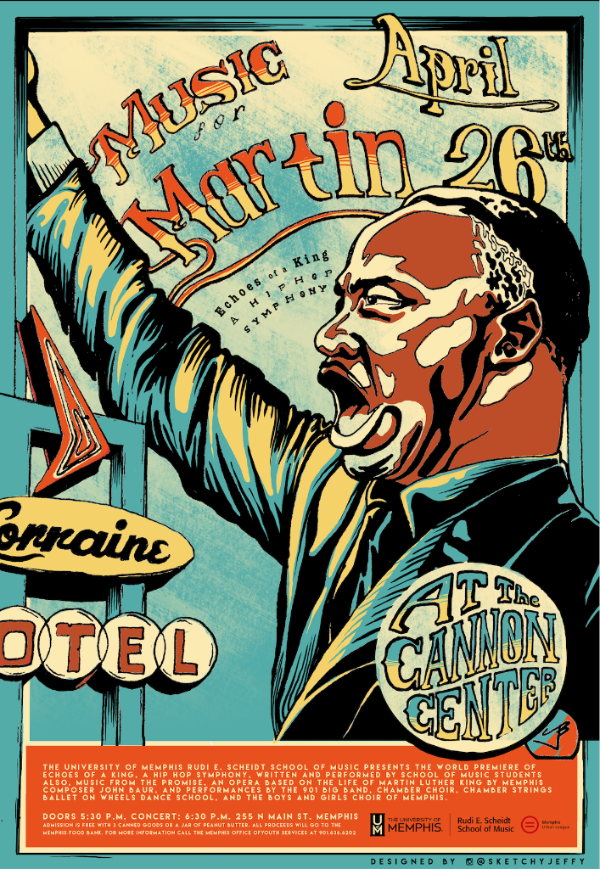

MLK 50

Next year is the 50th anniversary of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in Memphis, a tragedy whose consequences are still being felt today, in Memphis and all over the country. In the first of many upcoming commemorative events, Indie Memphis’ programmer Brandon Harris has put together a slate of films built around the theme of civil rights history and protest, beginning on Friday, November 3rd at the Hattiloo Theatre with Uptight!, a 1968 film directed by Jules Dassin. Shot in Detroit, the groundbreaking independent production, which tells a story of hope, paranoia, and betrayal among black militants, was inspired by John Ford’s The Informers and features a soundtrack by Stax legends Booker T. and the MGs.

Later that night at Studio on the Square, is Working In Protest, a documentary by Indie Memphis veterans Michael Galinsky and Suki Hawley. “This film covers 30 years of protest,” says Hawley. “We were documenting these events in a short form kind of way, because we felt like we had to. It was happening around us, and we are natural documentarians. We never really intended to make it a feature or something that would go to festivals. We just wanted to put it up on the internet and say, ‘Look what has happened around us yesterday.’ But then when we looked back, we realized that they all kind of connect. They show an evolution in the last 20 years of protest in the U.S.”

The film includes footage of demonstrations from both Democratic and Republican national conventions, as well as Occupy Wall Street, and the Moral Monday movement in North Carolina. “You see the rise of the militarization of the police,” says Galinsky. “It’s not a critique of protest, but you see a layer of ineffectiveness in our protest, and it raises a question of what we might do if we really want change.”

On Saturday afternoon, Wade Gardner will bring the conversation into the present day with his startling documentary. “Marvin Booker Was Murdered tells the story of a homeless street preacher whose family is from Memphis, Tennessee,” says the director.

Marvin Booker’s father was Rev. B. R. Booker, an AME church elder who was involved in the 1968 protests that brought Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to Memphis. Marvin met King as a child and, after the assassination, devoted his life to memorizing the civil rights leader’s speeches and spreading the message of justice and acceptance. “He was in Denver,” says Gardner, “and as he was waiting to be booked into jail, he was beaten to death by five jail guards. It was caught on video, witnessed by more than 20 people.”

Booker’s assailants were never indicted. “As soon as Marvin was killed, the cover-up began. The deputies got together to get their stories straight, and the demonization was in full force. The way they treated the Booker family was as if they had committed the crime.”

After the screening, Garner and the Booker family will be present to discuss the latest developments in the case and answer questions from the audience.

The MLK50 program includes a bloc of short films by Memphis filmmakers, including Katori Hall’s Arkabutla, Mark Goshen Jones’ Henry, and Myles by Kevin Brooks.

The BLM Bridge Protest: One Year Later is a documentary short by Commercial Appeal photojournalist Yolanda M. James, who was on hand on July 10, 2016 when 1,000 protesters shut down the Hernando De Soto bridge.

“One of the thoughts that ran through my mind was that I was documenting an historical moment, and I could not screw it up,” she recalls. “Memphis had not seen a protest this large since the 1960s, and it was important to record as much of this spontaneous event as possible. It was my day off, but I needed to be there to capture the news as it unfolded. At times I had to catch my breath because the scene had an overwhelming sense of captivating energy that genuinely touched my heart and spirit.”

The film combines audio interviews with activists and MPD Director Michael Rallings with images captured on the day of the protest. “We needed to hear their voices on how the event transpired, as well as to see if any changes were made to better relations between police and the community,” says James.

Abel Ferrara

Indie Memphis was founded by a group of independent filmmakers who wouldn’t take no for an answer, and through the last two decades, it has continued to celebrate that spirit of unfettered creation and expression. Few filmmakers fit that bill better than this year’s featured guest, Abel Ferrara.

The 66-year-old director made his debut in 1981 with the now-legendary exploitation film Ms. 45, a gritty tale of a mute woman, played by Zoë Lund, who takes bloody revenge on the men who raped her.

Indie Memphis will celebrate Ferrara’s uncompromising legacy with a double feature. The first is a 25th-anniversary screening of The Bad Lieutenant, the 1992 film written by Lund and Ferrara. Harvey Keitel stars as the most corrupt policeman imaginable, who spends his days smoking crack and shaking down innocent citizens for drug money. But the brutal murder of a nun awakens something in the unnamed officer, and he struggles to choose between redemption and ultimate damnation.

Ferrara will also host a screening of The Blackout, his 1997 feature starring Matthew Modine as a troubled man trying to reconstruct what happened during a wild night on the town in Miami with his friend, played by Dennis Hopper.

Lately, Ferrara has devoted himself to music. Alive in France is the director’s documentary of his band, the Flyz, on their European tour. It will screen on Saturday, November 4th, at 10:30 p.m. On Sunday, November 5th, the Flyz will play live at the Hi-Tone in Crosstown.

Good Grief

Good Grief

Kids on the playground ask tough questions like, “What kind of tool did your daddy use to kill your mommy?” These kinds of stories are related with disarming ease in Good Grief, a lively documentary about children who’ve lost parents or close care-givers, and a camp in Arkansas, that provides them with community, a place to heal, and how to manage when the playground’s not much fun.

Hopefully, the creative team behind this tightly wrapped documentary had a considerable budget for Kleenex. It’s hard to watch all 52 minutes with dry cheeks, and the tears it elicits — as likely to arise from rage or horror as sympathy — are never cheap or easy. As this candid, often wise film from co-directors Melissa Anderson Sweazy and Laura Jean Hocking reminds, there are many different kinds of feelings, and it’s okay to work through the whole spectrum.

Sweazy had a reasonable objective for Good Grief, which was named for Baptist Memorial Healthcare’s Kemmons Wilson Family Center for Good Grief. She and Hocking wanted to make a movie about living, not dying, and to tell the sophisticated, sometimes shocking story of a camp for grieving kids to people who might not normally respond enthusiastically to any or all of those words.

Good Grief introduces siblings Connor and Ava, whose mother was murdered by their father in a terrible act of domestic violence. It introduces Meaghan, whose brother AJ mistook their father for an intruder and, having been raised to use arms and defend himself and his family, shot through the door with tragic results. It introduces AJ, who recalls the whole story with clarity and insight. Also introduced are Angela Hamblen-Kelly, the executive director and visionary force behind the center, and the camp counselors and volunteers. Everyone onscreen has lost loved ones to illness, accident, and ongoing disasters

“We know hope exists; we see it every day,” Kelly explains. “Sometimes we let people hold onto us because we know it’s out there if they don’t. We let them know they can hang onto us until they can find it themselves.”

Death is a tough sell, but a hopeful outlook, lyrical visuals courtesy of cinematographer Sarah Fleming, and a sumptuous original soundtrack by Toby Vest and Krista Wroten Combest, make this potential downer float like a helium balloon. — Chris Davis

The Blackout

Twenty Years of Indie Memphis Memories

We asked filmmakers and audience members to share with us some of their favorite memories of the last two decades of Memphis’ premiere film festival.

My first real life moment as a filmmaker was seeing a film I made on a big screen for the first time in front of an audience. It was a wild experimental film that I’m sure was very trying for the audience, but the festival screened it nonetheless and a kind man by the name of Craig Brewer came to me afterwards and told me he liked what we were doing.

Whether that was the kindness in his heart or a genuine remark, it changed my path forever. I try to return that favor these days. I love seeing new filmmakers screen new films. There’s magic in those dark rooms when those images appear onto the screen.

Another favorite memory would be when I decided to propose to my now-husband in front of 350 people at the premiere of my documentary, This Is What Love in Action Looks Like. Having all of those special people in one room at the same time and being at the place where my religion is practiced, there was no place more fitting than on the stage at Indie Memphis — Morgan Jon Fox, filmmaker

Seeing [West Memphis 3 member] Jason Baldwin walk out, unannounced, onto the stage during the Q & A for Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory. — John Pickle, filmmaker

Jerry Lawler telling Andy Kaufman stories for 45 minutes after the screening of Man on the Moon. — Kent Osborne, actor, animator, and writer for Adventure Time

The entire 2011 festival is one of the best times I have ever had at a film festival. I ran into a lot of friends, made a lot of new friends, enjoyed as many of the non-screening activities as possible, and saw many great films. — Skizz Cyzyk, filmmaker, Indie Memphis jury member

I loved the days of screening on Beale Street and hanging out with filmmakers at the (then) less crowded bars after. — Stephen Stanley, producer/director

Screening my Destroy Memphis documentary last year, after waiting 10 years to find the right person to help me edit and get it on the screen. — Mike McCarthy, filmmaker

Occupy Indie Memphis. It was a timely and ridiculous premise for the Awards Show in 2011, and we shot the video sequences at the fest. People actually thought that a group of rejected filmmakers were protesting the festival. Chris Parnell even got in on the shenanigans! Every year feels like one big lock-in: You don’t sleep, you run around like crazy, and at least one of your friends cries. I love it! — Savannah Bearden, filmmaker/actor, and awards show producer

For a full list of films and a schedule of events, visit www.indiememphis.com.

Darius B. Williams for Striking Voices

Darius B. Williams for Striking Voices  Darius B. Williams for Striking Voices

Darius B. Williams for Striking Voices  Michael Donahue

Michael Donahue  Iseashia Thomas

Iseashia Thomas