Like all right-thinking Americans, I am a Turner Classic Movies (TCM) junkie. It’s the default channel I turn to when the cable box is on. By sheer coincidence, the night I returned from a screening of The Gift, I turned on TCM just in time to catch the beginning of Shadow of a Doubt, the 1943 film that Alfred Hitchcock considered his finest work.

Writer/director/producer/actor Joel Edgerton has clearly studied Hitchcock, and his new film The Gift carries much of Shadow of a Doubt in its DNA. It begins with a young couple Simon (Jason Bateman) and Robyn (Rebecca Hall) buying a Southern California, midcentury modern home. They’re relocating from Chicago because Simon has a prestigious, high-paying new job in “corporate security.”

You just know they’ll soon come to regret those huge windows that blur the lines between outdoors and indoors. They’re shopping at Ikea, when someone recognizes Simon: Gordon “Gordo” Mosley, played by our director Edgerton. Simon grew up in the area before leaving for college and career, and Gordo was a high school friend. Or maybe “friend” is an overstatement. Simon seems pretty reluctant to talk to him, and reveals to Robyn that the kids used to call him “Gordo the Weirdo.”

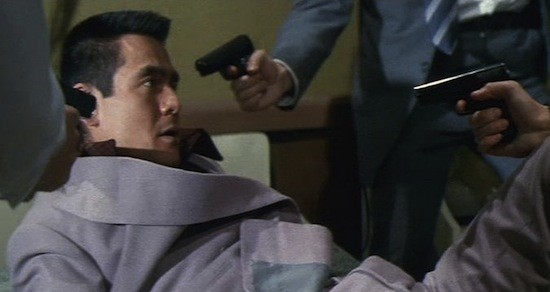

Writer/director Joel Edgerton stars in The Gift

Edgerton’s portrayal of Gordo is one of the best things about The Gift. He’s an Iraq War veteran, plain-spoken, and down-to-earth, but somehow unsettling. He’s just a little too stare-y, and his simple statements like “Good people deserve good things” seem to carry sinister subtexts. He gives off a weird stalker vibe even before the first unsolicited gift arrives at Simon and Robyn’s house.

But then again, nearly everyone in the film is giving off bad vibes. Robyn’s got major problems. She had a miscarraige back in Chicago and is the only person in the film who doesn’t drink copious amounts of wine, because she’s in recovery for unspecified substance abuse. Employees at Simon’s new company are clearly a bunch of status-obsessed creeps. And Simon is the worst of all. Bateman’s finest work has been as Michael Bluth on Arrested Development. Much of the show’s comedy comes from the fact that the Bluth family is hopelessly entitled and clueless to their own foolishness. Michael is the most sympathetic of the lot, but that’s only by comparison with the other characters. Imagine how annoying Michael Bluth would be if you knew him in real life, and you’ve got a sense of how Bateman’s performance plays out in The Gift.

Gordo makes references to “letting bygones be bygones,” and as his presence in their lives grows more insistent and sinister, Robyn wants to know what kind of history he and Simon have. In Shadow of a Doubt‘s, opening scene, Hitch makes sure the audience knows that Joseph Cotten is not the good-hearted Uncle Charlie his family thinks he is. The simple tension created by the informational asymmetry between the audience and the characters imbues every one of Uncle Charlie’s innocuous actions with a sinister undertone. Edgerton attempts the opposite. He wants you to wonder who is the real bad guy, Gordo The Weirdo, Simon, California start-up culture, or maybe even us, the audience.

The Gift is a tricky film to review, because I think Edgerton has his heart in the right place. He clearly wants to do some classical suspense filmmaking, and his influences are pointing him in the right directions. And yet, this film comes off as less a Hitchcockian thriller than as a low-rent Gone Girl. As with last year’s David Fincher hit, the real fear the film is tapping into is the failing middle class’ economic anxiety. Simon seems to shun Gordo because he’s a reminder of Simon’s working-class past, and Gordo goes to great lengths to fake affluence. But The Gift lacks either Fincher’s talent for dense plotting or Hitchcock’s elegance. Long passages in the middle seem repetitive, as Edgerton leans on jump-scares over and over. And the less said about the ending, the better.

If you’re a fan of suspense, and want to support original material, give The Gift a whirl. Edgerton’s a gifted actor, and shows promise behind the camera. Here’s hoping the pieces come together better in his next outing.