In a special edition of the Time Warp Drive-In, Memphis auteur Mike McCarthy and Black Lodge Video’s Matthew Martin celebrate Elvis Presely’s film career on the 37th anniversary of his death.

The program kicks off with Jailhouse Rock, Elvis’ third and greatest film appearance. By the time it premiered in 1957, Elvis had already changed popular music forever and cemented his place as the biggest music star in the world. But to Elvis, true immortality meant film. He idolized Marlon Brando, and his performance in Jailhouse Rock owes much to Brando’s sensitive biker warlord in The Wild One. The plot is a paper thin extrapolation of Elvis’ bad boy public image, but it hardly matters. Elvis is at the height of his musical power and raw sexual charisma. The film’s centerpiece is a Busby Berkley style musical number of the title song, but even its antiquated and stylized setting doesn’t take the edge off the song or Elvis’ performance. The sequence has been copied dozens of times and remains an ideal towards which all subsequent music videos aspire to.

Time Warp Drive-In Pays Tribute To Elvis

After a “headlight vigil” is Viva Las Vegas. As Elvis’ film career went on, the quality of his films slowly declined, as he pumped out quick, but profitable, product throughout the 60s. But 1964’s Viva Las Vegas is the exception, primarily for one reason: Ann Margaret. Many of Elvis’ endless parade of love interests were one-note bimbos (Mary Tyler Moore excepted), but Ann Margaret was an exceptionally talented dancer and, if not exactly a great actress, a natural movie star with a personality as big as her halo of fiery red hair. She and Elvis had a torrid affair during and after the shooting of the film, and it shows on the screen big time. Acting or no, it’s clear that these two beautiful people can barely keep their hands off of each other. Add in a classic title song better than most of Elvis’ 60s output and it equaled the biggest grossing film of Elvis’ career.

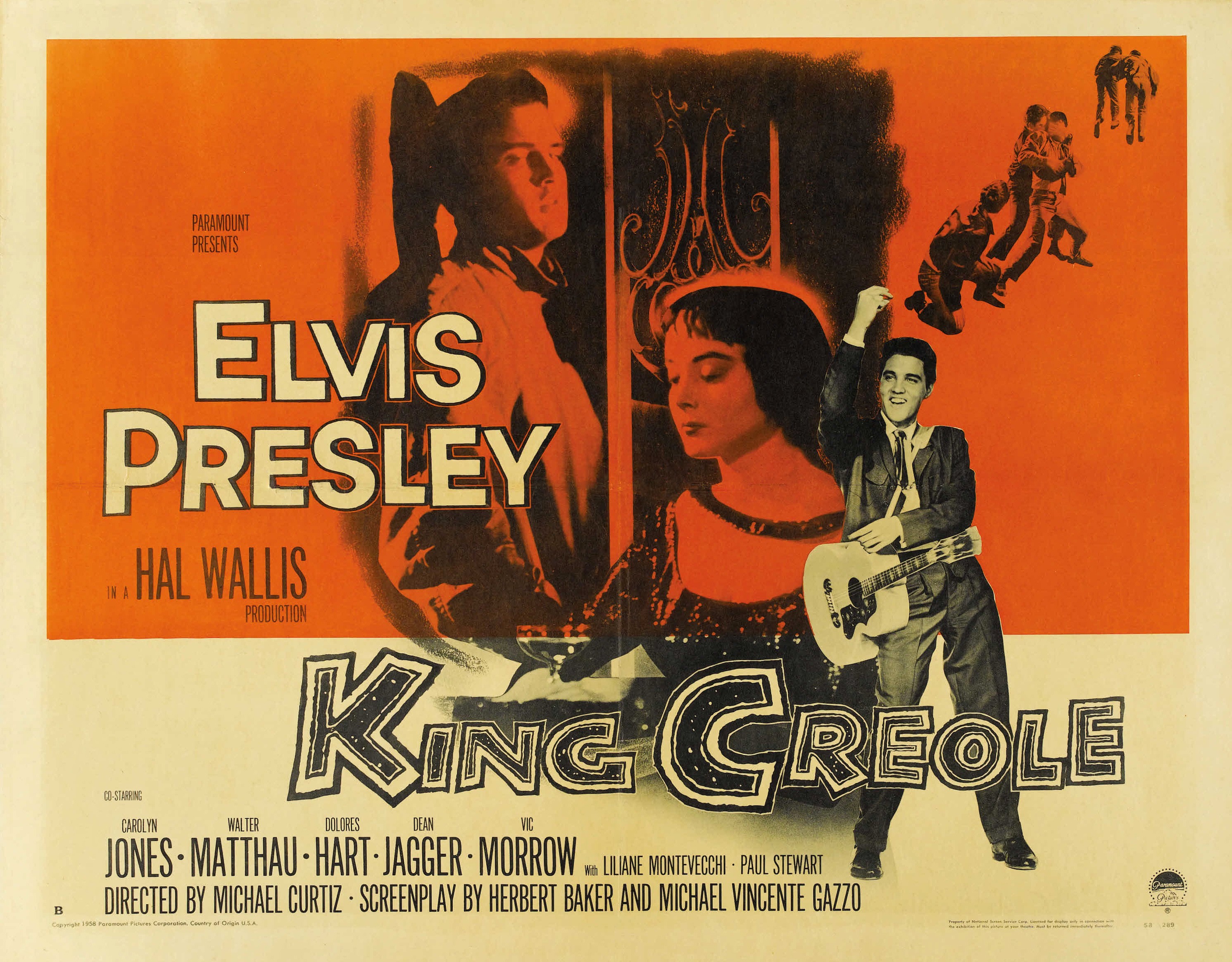

Next is King Creole. Directed by the legendary Michael Curtiz, whose filmography includes Casablanca. Said to be Elvis’ favorite role, his turn as Danny Fisher, New Orleans street urchin turned caberet singer is certainly his best film performance, rivaling James Dean in Rebel Without A Cause.

Time Warp Drive-In Pays Tribute To Elvis (2)

The evening ends with The King’s 1972 swan song, Elvis On Tour. The concert documentary features performances filmed over four nights in 1972 interspersed with backstage footage and an interview. This is Elvis in full Las Vegas jumpsuit trim. His voice is strong, and his stage presence unmatched among mere humans, but it’s clear that he doesn’t have the same intensity as the man who was swinging from a pole in Jailhouse Rock. But after the extraordinary life he led, you’d be a little blasé about playing coliseums as well.

The Time Warp Drive In begins at dusk on Saturday, August 16 at the Malco Summer 4 Drive-In.