“I haven’t had a single person reach out to me yet,” says Pat Surratt, whose Lamar Avenue property suddenly became infamous after an enormous gray zombie was painted on one of its exterior walls last September.

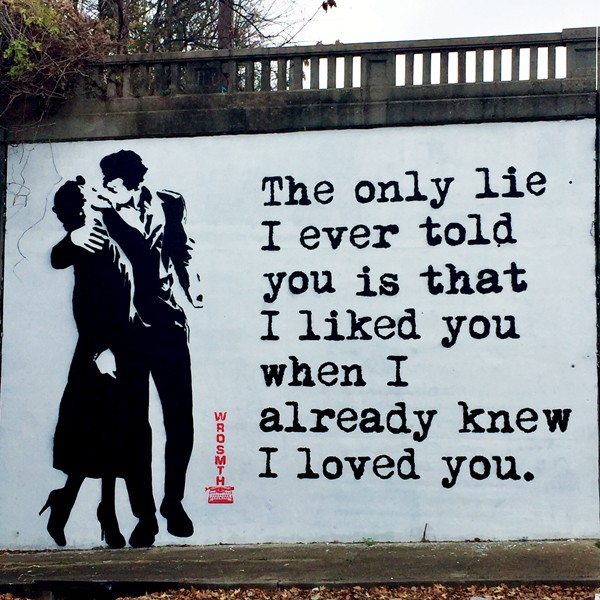

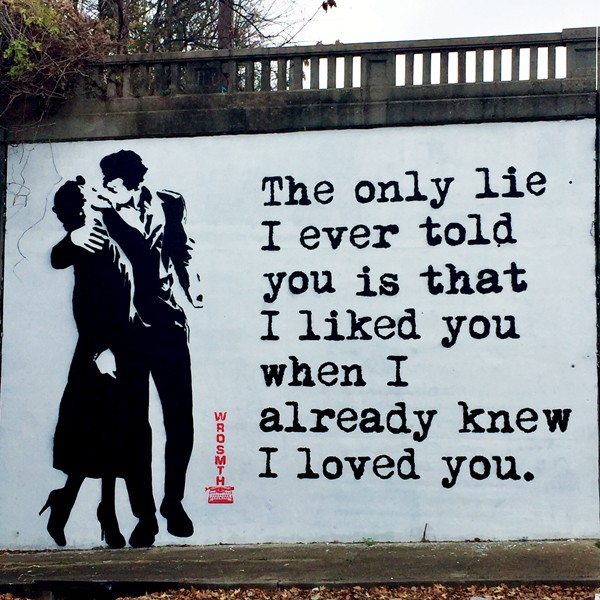

Since that time, the mural has been denounced as “satanic” by Memphis City Council members, has been featured on several local TV news broadcasts, and has become fodder for reports and editorials in various local publications. Everything came to a boil last week at city council, when Chairman Berlin Boyd quoted scripture and said the city would draft letters to begin a process of removing the mural.

Lamar Avenue property owner Pat Surratt doesn’t mind the zombies — and wouldn’t be opposed to a pirate zombie either.

All this public sturm und drang remains something of a mystery to Surratt, who says nobody from the city, media, or neighborhood has contacted him to complain, seek compromise, or to even ask, “Hey Pat, what’s up with that ugly zombie on your wall?”

“It kind of blew me away,” Surratt says, describing the disconcerting experience of hearing no complaints from pundits or politicians who ignored the neighborhood as it slid into decay, then being criticized about a painted cartoon monster straight out of Scooby-Doo.

The zombie is just one of dozens of murals around the city that have been painted under the auspices of Karen Golightly’s not-for-profit group Paint Memphis. To be fair, when art groups like Paint Memphis are described as “occultists” in City Council meetings and politicians speechify on art’s power to create demonic “fixation” in people’s minds, it’s hard not to get distracted by the show.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

murals featuring music icons, butterflies, and, you guessed it, zombies.

“Everybody’s yelling and pointing fingers, and not a single person has reached out to me,” Surratt says. “I’ve seen stories from every news organization in town, I think, from the Daily News to the Memphis Business Journal. But none of them have called me. They’re all talking about what the city council is saying.

“It’s great you have somebody up there doing what they do,” says Surratt, who’s been enlisting artists to brighten his overlooked corner since 2015, when he sought out artists to create a Memphis music wall honoring Willie Mitchell, Johnny Cash, Otis Redding, and others. “But it seems to me this isn’t really about the art or about what can be done to help the neighborhood. It seems like some people just want to get more attention for themselves.”

If the City Council follows through and launches a process of removal, Surratt will finally become a part of the conversation. First, a notice will arrive asking him to remove the artwork, which can’t be considered graffiti since it was created with the owner’s consent. Then, if the owner refuses to comply — which is likely — the whole matter gets turned over to Environmental Court, where Judge Larry Potter will determine whether or not the zombie painting is a nuisance.

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

“I don’t regret anything,” says Surratt, who wants to sell the Lamar property and says he’s encouraged by all the positive attention that’s been paid to his little strip since the music wall went up. And he’s thankful for his partnership with Paint Memphis, a two-year-old organization that facilitates an annual muraling festival.

In 2017, Paint Memphis brought more than 150 artists to Surratt’s neighborhood to create works on more than 33,000 square feet of public and private walls for the largest collaborative outdoor painting project in Tennessee.

“There just wasn’t much here to look at before,” Surratt says of the space his buildings occupy — near where South Willett meets Lamar and where Midtown more or less crashes into South Memphis. It’s a stretch of urban connective tissue defined by a concrete train trestle and underpass where the Rozelle, Glenview, and Cooper-Young neighborhoods merge into one another. “It’s mostly just us, the old Lamar Theater, and Payne’s Barbecue,” Surratt says. “Before the murals, it was so easy to just drive past us and never look twice.”

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Though it’s hidden from the road by virtue of being below ground, one of the area’s most dynamic spaces is the Altown skateboard park, a community-driven DIY space, which also received the Paint Memphis treatment in 2017.

Zombie Apocalypse: The Battle Over a Paint Memphis Mural

Paint Memphis founder Golightly says she’s ultimately happy for the attention and thankful so many people are talking about public art. She says it’s paid dividends in the form of new board members, new donors, and more calls about commissioned murals than she’s fielded since launching the project in 2015.

Golightly is a Mobile, Alabama, native who graduated from Rhodes College in 1989 before pursuing advanced degrees at the University of Memphis and the University of Southern Illinois. She’s an author and an associate professor of English at Christian Brothers University who started photographing and writing about street art while traveling across the U.S. and Europe, wondering why the kinds of vibrant public art spaces she found in other cities weren’t more prevalent in an artist-rich place like Memphis.

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

That’s when she started learning about public policy and permission walls, where street artists, fine artists, and any other kind of artists are allowed to paint whenever they like without seeking advance permission. She started exploring all the reasons a city might want to use graffiti artists as a resource instead of treating them like a problem. This is the slow-burning origin story of Paint Memphis.

“The corps of engineers agrees with us,” Golightly says, launching into a street art catechism. “Paint preserves concrete.” It’s a practical beginning to a conversation about empowerment, community, and collaboration.

Paint Memphis puts out national calls and chooses artists based on examples of past work. It brings local artists together with schools, community groups, and wall painters from as far away as Seattle and Los Angeles. Nobody gets paid, but everybody gets fed and works together, following a set of guidelines that were developed in conjunction with the city and residents of the Chelsea/Evergreen area where Paint Memphis created its first mass-scale collaborative mural. The rules to date are basic: no nudity, no profanity, and no gang signs or imagery.

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

Golightly acknowledges that she didn’t directly engage nearly as much with the neighborhoods touching Lamar and South Willett as she did before turning artists loose on the Chelsea Avenue flood wall on an earlier project. As part of an effort to improve future community relations, Paint Memphis has created its first intern position and tasked the new hire with creating more opportunities for neighborhood participation.

Still, Golightly, who also faced criticism for a grotesque image of Elvis Presley with a snake embedded in his face, wonders if even a more perfect process would have kept the undead from rising over South Memphis. “‘No zombies’ is a pretty specific request,” she says. “But who knows, maybe somebody would have said ‘No zombies.'”

Golightly prefers to keep aesthetics out of the debate in favor of conversations about mission, the law, and building a better process. Her points about arguing taste were driven home at last Tuesday’s City Council meeting, when anti-zombie council member Jamita Swearengen and a handful of like-minded residents engaged in a bit of art criticism.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

“A true, voluptuous black woman in a bikini — that’s coming back to life,” one man said, offering his opinions on the meaning of positive, family-friendly art and resurrection imagery.

Although he was never asked, Surratt also has some thoughts about about sprucing up the zombie. He thinks people might be more open to a monster mural if one of the gray guy’s eyeballs wasn’t hanging out. “Maybe we could give him an eyepatch,” Surratt says, imagining what kind of response a pirate zombie might elicit. “We could give him a beard and hat at Christmas. Paint him like Uncle Sam for the 4th of July.”

Golightly doesn’t want anybody to put an eyepatch on the zombie, but she isn’t entirely opposed to repainting certain areas after a reasonable period of time. “I don’t like to paint in places we’ve already been,” she says, pointing to the other things her organization does, in addition to creating murals. “The area around the Chelsea wall had literally become a dump,” she says, describing a weedy stretch where the city had stopped mowing and people had begun to toss old mattresses and tires. “All of that had to be cleaned up and removed. On Willett, we removed like three dead animals and I don’t know how many dirty diapers.”

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

The goal, she says, is to keep moving forward, cleaning up and covering decay with fresh coats. But sometimes editing happens.

“Nobody said anything about the Chelsea wall for the most part,” Golightly says. “But, on the end-piece, someone painted a skeleton holding a scythe, and a minister came to me and said people didn’t want to see images associated with death. He asked if I could fix it, and I said I didn’t know if I could.” The problem was solved when Saint George’s school contacted Golightly looking for a project. She gave them the controversial section of the Chelsea wall, and now there’s an angel where the grim reaper stood.

“People need to actually go out and see the work for themselves,” Golightly says, adding that pictures of individual sections don’t really do the sprawling art experience justice. The two zombie murals have gotten so much attention, it’s easy to forget they’re a relatively small part of a 33,000 square foot project. “Nobody’s going to like everything,” Golightly says. “But you’re going to like something.”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Karen Golightly

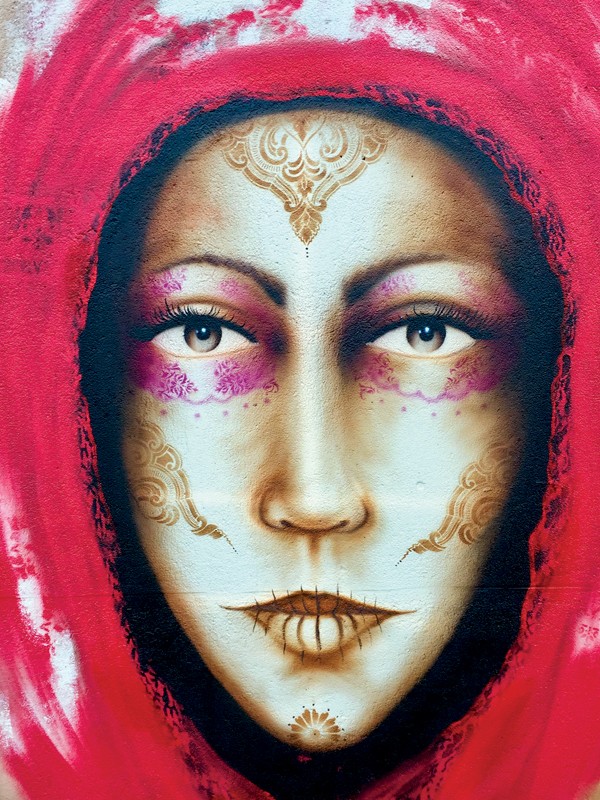

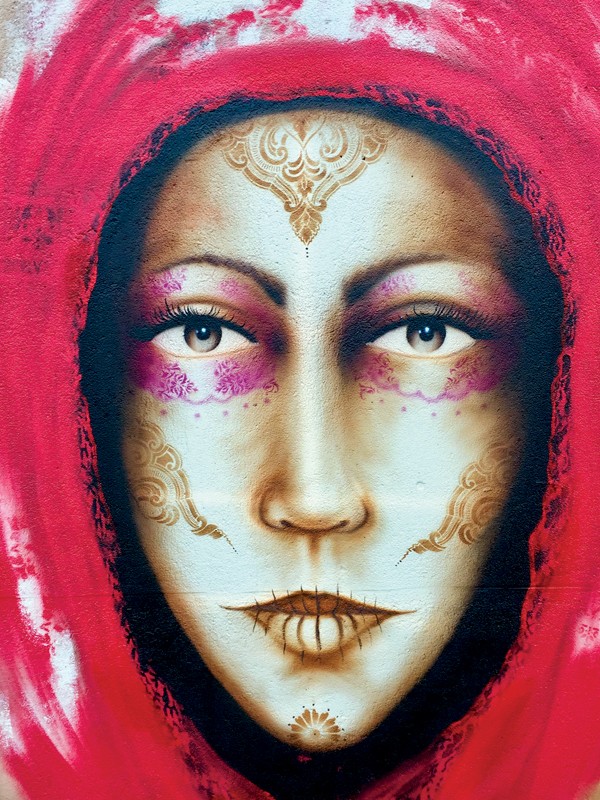

In addition to zombies, the artists of Paint Memphis 2017 created wavy psychedelic worlds in an underpass beneath the train tracks. They painted pictures of flowers and faces alongside fantastic birds and beasts. Visitors will see Memphis musicians, comedians, and actors. Country music icon Hank Williams inexplicably takes up space across the road from a pair of Beale Street musicians, just around the corner from hula hoopers and a wall dedicated to sponsors and partners, including Clean Memphis, Art Center, and the National Endowment for the Arts. There are realistic paintings of people and places, and conceptual work like “Bulletproof,” by Jamond Bullock, a fine arts grad from Lemoyne Owen College, whose surreal image of a pyramid and lips holding a smoking bullet leaves viewers with something to talk about.

“Sometimes you have those people to step in front of you and become dream killers and they become like a bullet,” says Bullock, a busy artist who ships his art all over the world and has murals in Orange Mound, on South Main, and in Soulsville across the street from the Stax Museum. “This person is catching the bullet. Instead of letting their dreams be killed, they’re stopping the person who’s killing their dreams.”

Bullock’s popular “A Day in the Life” mural attracts tourists who have their picture made in front the work’s giant butterfly wings. He’s been making murals with Paint Memphis from the beginning and describes the work as a positive experience that’s allowed him to network with artists he wouldn’t have met otherwise. Artists like Nashville painter Brad Wells who died in December 2015 and is the only Paint Memphis artist to have his work treated with an anti-graffiti coating to preserve it from being painted over.

Chris Davis

Chris Davis

“It’s a painting of a butterfly on a flower,” Golightly says of the one preserved image. “I don’t think it’s going to upset anybody.”

The grotesque Lamar Avenue zombie and his lovely bed of roses is another story entirely. It divides viewers — and politicians — who are split as to whether it’s a positive or negative image for residents, motorists, and passers-by. But whether he’s positive, negative, satanic, or a one-eyed angel of pure light, Surratt wants to keep him around. Golightly says any attempt to remove him without a court nuisance ruling becomes a First Amendment problem. So, like factions in a post apocalyptic fantasy, the various factions are hunkering down and preparing for a fight over zombies.

[slideshow-1]

UrbanArts Commission

UrbanArts Commission  UrbanArts Commission

UrbanArts Commission  UrbanArts Commission

UrbanArts Commission

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Chris Davis

Chris Davis  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Chris Davis

Chris Davis