A large portrait of Bach hangs in William Eggleston’s apartment; pivot to the left and you’ll see stacks of oscilloscopes and other electronic modules, green waveforms pulsing; pivot again and you’ll see his treasured Bösendorfer grand piano. Such disparate images capture both his love of music and the contradictions inherent in it. Of course, one must begin with the disconnect between his notoriety as one of the most compelling fine art photographers in the world and the fact that his latest project has nothing to do with photography at all — at least on the surface. His debut album, Musik, released last month on the Secretly Canadian label, explores his other great passion, one that blossomed long before he had his first camera.

“I began playing classical music when I was about four,” he explains, adding that “I have an ability to play anything I’ve heard.” Indeed, he is completely self-taught. “We had a piano in the hallway of our home. Whenever I’d pass through, I’d stop and play something.” Eventually, he deciphered musical notation, but his playing has always sprung from his ears more than his eyes. “People that are really good at sight reading, generally that’s the only thing they’re good at. Without the score, they can’t play a damn thing. Sight-reading is not musicianship to me.”

Alex Greene

Alex Greene

William Eggleston at home

That’s a rare opinion for a classical music fan. Yet Eggleston listens to practically nothing else. He remains disdainful of most rock music, from Elvis Presley to Alex Chilton (despite having been a close friend of the Chilton family). And he’s even skeptical of jazz. This is especially paradoxical, as nearly all of Eggleston’s own recorded output is entirely improvised. Nonetheless, its closest stylistic affinity is with the harmonies and cadences of orchestral classical music.

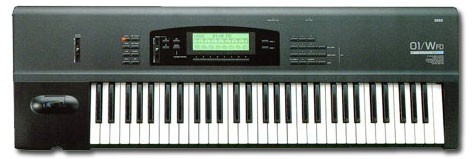

For an artist who resolutely uses only real film stock, it’s ironic that his orchestral ambitions were made possible by modern digital synthesis. In the early 1990s, after a lifetime of playing piano, Eggleston discovered the Korg 01/W sampling keyboard, able to trigger hundreds of different orchestral sounds simultaneously with a split keyboard: cellos with the left hand, flutes with the right, and so on. His love for finely crafted machines, from guns to cameras, now extended to the Korg. “It’s manufactured in Tokyo, but a hundred percent of it is a bunch of engineers in California,” he notes admiringly. “It makes maybe a billion different sounds. When this model of Korg came out, I was so enchanted with the machine.” In fact, he bought four of them. And as he began improvising symphonies on the spot, the machine would record his every move.

Korg 01/W

“The machine has a memory, but also it has a floppy disc drive. And once you cut the power off of the machine, the memory’s erased. If you’re lucky, you’ve made a disc from the memory, which sounds just like it did when played.” Eggleston would improvise one orchestral piece after another, compiling many hours of music. His friends and family were the only listeners privy to these works, though readers of Robert Gordon’s It Came from Memphis got a taste from that book’s accompanying CD, which included an excerpt from the then-freshly recorded “Symphony #4, Bonnie Prince Charlie.” (As Eggleston notes, “I’m very much interested in Robert Burns.”) But after that initial exposure and a flurry of such spontaneous “compositions,” Eggleston’s recorded output tapered off.

“Now, this release that these people are doing was not my idea. I had nothing to do with it,” he notes. “This fellow, Tom Lunt, is the main force behind [Secretly Canadian’s] productions. And he’s been here a lot of times. All told, we went through something like 60 hours of music, all from floppy discs. I had tons of them.” None of the music was recorded in a conventional sense. “They would say, ‘Well, you must overdub.’ No. It was just straight, accurate recordings of what was played.” Each floppy disc was a snapshot of what he produced when sitting at the Korg.

The snapshot metaphor is apropos, given the artist’s freewheeling approach to photography, whereby he riffs off images encountered in everyday life. This tactic is especially apparent in the film Stranded in Canton, edited down from many hours of unstaged video footage that Eggleston shot on the fly in the mid-’70s. He is quick to affirm the similarity between improvised music and what Henri Cartier-Bresson called the “decisive moment” to which a photographer must always be attuned.

But don’t expect Eggleston to reprise his Musik in a live setting anytime soon. “I don’t do public performances,” he says. “I really play for myself and a select group of friends that might drop in. I’m delighted to play for them. Concerts, public performances — not interested. It wouldn’t be difficult. I don’t have any form of stage fright. So it wouldn’t mean anything to me, except a career like that is just a hell of a lot of trouble.”