Next month, the Tennessee Historical Commission, a group of 28 people from all over the state, most of them white, will tell Memphians whether or not they can remove a huge statue of Nathan Bedford Forrest, a man who was once Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan and made a fortune trading slaves, from a public place in this majority African-American city.

After Dylann Roof, a self-confessed white supremacist, shot and killed nine African-American churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015, Memphis leaders rushed to remove the statue. But state lawmakers tightened rules on the removal of such monuments, requiring a super-majority approval of the Tennessee Historical Commission (THC) instead of a simple majority vote.

Allan Wade, the Memphis City Council’s attorney, and others continued to work on the issue.

Then came the tiki-torch-bearing white supremacists to Charlottesville, Virginia, in August. By the time the Unite the Right rally weekend was over, dozens of counter-protestors were injured and one woman, Heather Heyer, was murdered as James Alex Fields, a Nazi-loving 20 year old from Ohio, rammed his Dodge Challenger into the crowd.

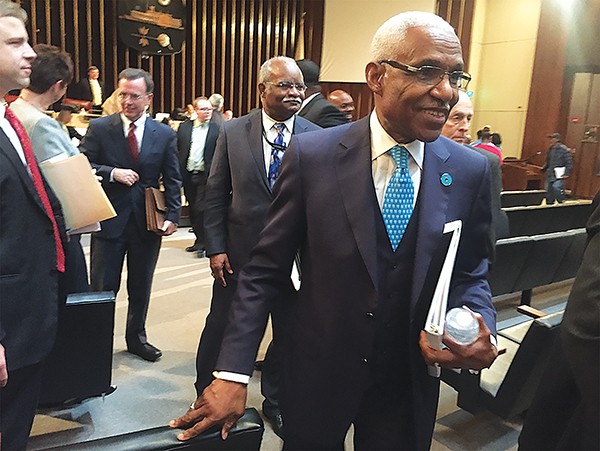

In Memphis, hundreds gathered in protest around the Forrest statue and the Jefferson Davis statue downtown. They demanded immediate action, but Mayor Jim Strickland, who has also called for the statues’ removal, said his administration would follow the rule of law on the matter. That means waiting on the October vote of THC members, who voted Friday to leave a bust of Forrest in the Tennessee State Capitol building.

But even if the commission denies the city the right to remove the statue, city leaders have been working on other plans. What follows is a look at how we got here — and where we might be headed. — Toby Sells

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

“The Right Thing”

As this Flyer goes to press, the Memphis City Council is set to vote on resolutions to remove or board up the city’s two confederate statues.

Council Chairman Berlin Boyd says council members are “united and [have] unequivocally expressed the will of a vast majority of the citizenry that these reminders of hatred and bigotry have no place in our community.

“We renamed Confederate, Jefferson Davis, and Nathan Bedford Forrest Parks over four years ago, and we have been trying for two years to do the right thing for this community by removing these two statues,” Boyd continues. “The only thing standing in our way has been the people who have created obstacles that have prevented us from exercising what is in the best interest of our citizens.”

The resolutions are based on four concepts presented to the council’s executive committee in late August by council attorney Wade.

Of the options, Wade says the first — immediately removing the statues, followed by destruction or storage — would be the most “drastic” and by law requires a waiver from the THC. But Wade says this action could be taken if the statues are declared a “public nuisance,” similar to the case made for the confederate statues in New Orleans.

Citing a provision of the Civil Rights Act, Wade says an additional argument could be made that the existence of the statues in public parks is discriminatory and prevents African Americans from fully enjoying those public spaces.

But, Wade says, this is not an action the city should pursue without first alerting the state’s attorney general. “I don’t think we should just go and yank them down tomorrow without some due process occurring,” he says.

The second option he presented is the sale of the monuments at an auction or private sale, which Wade says also cannot be done without a waiver. But he says designating a resting place for the statues could aid in the waiver process.

Wade told the council that it’s “probably easier to have someone executed by lethal injection in Tennessee than to receive a waiver from the state’s historical commission,” and that the waiver process would take at least a year.

Though the pending waiver for the removal of the Forrest statue will only require a simple majority to be approved, Wade says the process includes a laundry list of actions that must be taken leading up to the hearing.

Wade told the council committee that the third option — requesting that Governor Bill Haslam seek a special session of the THC — would expedite the waiver process, but Haslam, although an expressed supporter of having the statues removed, has said he will not ask for a special session.

The last option is boarding up the statues. Wade says this temporary option does not require a waiver and could be done in the interim waiting period. Wade says by law, the city is allowed to board up the statues for their “preservation” or “protection.”

He says there is a foundation for this action because the city has already had to invest tens of thousands of dollars to protect and maintain the statues.

However, city attorney Bruce McMullen says the city is seeking a permanent solution and is “not in the business of protecting the statues.”

Mayor Strickland says the city will only seek to remove them legally. If the waiver is not granted by the THC in October, city officials say there are still other viable lawful actions.

“For some time now, the mayor has been working on building consensus to make our goal a reality,” said Ursula Madden, the mayor’s chief communications officer. “If our waiver request is not successful, our pursuit does not end. We have other lawful options to turn to.”

One of those options might be going around the law stating that a waiver is needed to modify or move historic property. The parks could be sold to a proxy, who would then have the statues removed before selling the parks back to the city. — Maya Smith

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

The statue of Jefferson Davis in a downtown park

Smooth Agitator

Tami Sawyer’s smart as hell, and she’s not going to take it anymore.

“But what about the black guys?” The question sounds awkward when asked like that, but smoother variations appear in practically every online argument against the removal of Memphis’ public memorials to Nathan Bedford Forrest and Jefferson Davis.

Memphis Mayor W.W. Herenton didn’t remove the offending monuments when he was in office eight years ago, and he’s black. His successor, A C Wharton, didn’t take them down either, and he’s black, too.

So, why is a diverse group of activists, led by #takeemdown organizer Sawyer, being so hard on the white guy in the mayor’s office who says he’s doing everything he can within the framework of the law to remove Forrest and Davis from undeserved places of honor in public memory?

For starters, Sawyer — an uncommonly cool-headed firebrand — doesn’t buy Mayor Strickland’s narrative.

“The law is unjust,” she states, flatly criticizing a Tennessee ordinance preventing the removal of confederate statues in Tennessee. “No other statues in the state have that kind of protection.”

Sawyer recognizes earlier, failed attempts to remove Forrest and Davis, but says, “we’re trying to do this now.” She’s got no issues with criticizing Herenton and Wharton “when we’re talking about the historic achievements of our former mayors.” But, she says, it has “nothing to do with right now. It has no bearing on what the current administration chooses to do.”

Sawyer is a Memphis native, a St. Mary’s grad, and the director of diversity and cultural competence for Teach for America. She jumped into activism with Black Lives Matter three years ago, and into politics in 2016, when she gave House District 90 incumbent John DeBerry a run for his money. Steeped in history and cultural literacy, Sawyer’s activism, like her campaign, was born of frustration.

“I guess it makes sense,” says Sawyer, who practically grew up backstage at the National Civil Rights Museum, where her father once served as chief financial officer. “Martin Luther King died here, and it feels like a lot of hope and a lot of gumption died here, too. We’re really stuck on history, not progress, and I think that’s what makes me sad.”

“There’s a lot of old white money making a lot of decisions in a majority-black city, and there’s no such thing as old black money,” Sawyer continues.

That’s a situation she wants to change, and she believes removal of the confederate memorials is as good a place to start as any.

“If we can’t even get these statues down, how are we going to get something done about the big issues?” she says. “The conversations we have are about how black people, poor white people, and brown people are uneducated and reckless. They don’t care about their kids and have too much sex, so they have too many kids. And they’re killing each other and stealing from each other, and they don’t care about anything. We don’t talk about what it means to spend more money on cops than education or to build more prisons than schools.”

Sawyer doesn’t think statue removal is merely symbolic. “You’re in a 65-percent black city with [a statue of] the Grand Wizard, or whatever big man [Forrest] was in the early days of the Ku Klux Klan,” she says. “I can tell you all the stories about what [he] said or did, but the bottom line is, [Forrest and Davis] felt they were superior to black people and their treatment of black people was odious at best. I can’t think, outside of Native Americans, of another group of people that are told to just take it.”

When asked why she’s not satisfied with the mayor’s plan to work inside the law, Sawyer cites city council attorney Wade, who’s on record as saying the state law exists to ensure no confederate statue in Tennessee will ever be removed.

“[Stricklend] could have let us cover the statue,” Sawyer says, recalling a recent protest and fishing for some evidence of good faith. “Instead [he] sent [his] soldiers in, like we were on a battlefield.”

Sawyer’s activism comes at a cost to her and her family. “My parents always know where I am,” she says, describing an informal check-in ritual the Sawyers adopted when things got weird. “To get a text from your child saying, ‘Hey here’s my new number because I was woken up this morning by white supremacist on my cell phone.’ That’s tough.”

“It creates stress in the family,” Sawyer admits. “They’re supportive, but it’s hard not to sometimes say, ‘Oh, I wish you’d just have a seat.'”

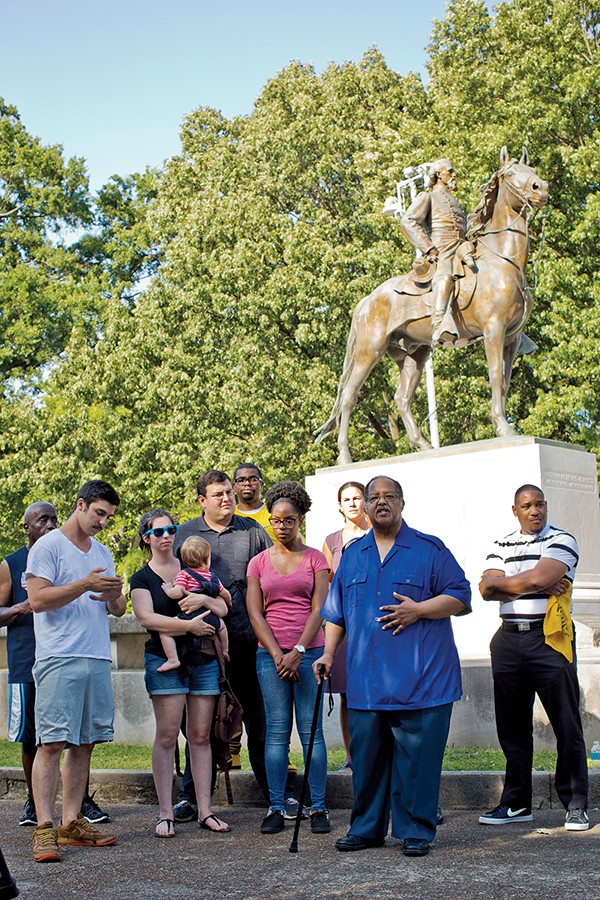

What keeps her going? Last June, a student from Memphis’ Grad Academy discussed the monument in Health Sciences Park. “All my life, I’ve passed that statue,” she [the student] said. “And all my life, I thought that must be somebody important.”

That, Sawyer says, cannot stand.

“No, it doesn’t oppress you everyday,” she says, “but any time it comes into your awareness, it’s like, that’s awful. And it’s in my city.” — Chris Davis

(For the full Q&A with Tami Sawyer visit memphisflyer.com.)

Crowds gathered in Health Sciences park to advocate for the removal of the statue of Nathan Bedford Forrest.

The Saga Of Memphis’ Forrest Statue

All things considered, it’s a wonder that it’s taken this long for a truly serious effort to be launched to remove the Nathan Bedford Forrest statue from a prominent downtown park.

There are few things more apt to give confederate nostalgia a bad name than a swarm of militant neo-Nazis, marching with torches, shouting anti-Semitic slogans, and thrusting out stiff-arm salutes.

And if that vicarious tarnish, famously enacted in Charlottesville, Virginia, was enough to finish off a statue of Robert E. Lee, a respected military commander hitherto given a pass on the strength of a claim that he had only taken up arms during the Civil War to defend his native state of Virginia, consider the actual deeds attributed to the erstwhile “Wizard of the Saddle,” Nathan Bedford Forrest — a slave trader before the Civil War; the supposed author of a massacre of surrendering black troops at Fort Pillow, Tennessee, during the war; and the first Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan after the war.

That’s a hat trick of infamy. Though, to be sure, the general, a certified tactical genius, has had apologists eager to deny or soft-pedal those accusations, none more active and prominent than the N.B. Forrest Camp 215 of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, which raised some $10,000 to erect a large granite sign bearing large black letters saying “FORREST PARK” in late 2012.

The erection of the sign was an act of hubris, the breach of an unofficial truce between supporters and detractors of the Forrest statue that had held since the last previous dustup in 2005.

Tempers were ultimately cooled back then, at least partly due to the attitude of then-Mayor W.W. Herenton, who opposed “outside agitators” like Al Sharpton, who had joined local officials and clergy to demand a change in the status of the park, a removal of the monument, and a relocation of the graves of Forrest and his wife, which lay underneath the memorial and had been transplanted there from Elmwood Cemetery in 1905.

It was a turn-of-the-century era characterized by the Supreme Court decision Plessy v. Ferguson, which sanctioned Southern segregation measures or at least acquiesced in them.

The tide of history, including a full-fledged civil rights revolution, had conspicuously turned by the time of the 2005 controversy, which ended in a sort of stand-off — one that was accepted, though reluctantly, even by Walter Bailey, the venerable Shelby County commissioner and civil rights activist.

But the provocative appearance in 2012 of that that new sign upped the ante in what had become a simmering conflict over the very meaning and symbolism of the confederacy.

Bailey and others cried foul over the new sign, and in the resulting uproar, both the city council and then-mayor Wharton publicly called for the relocation of the Forrest statue and graves.

Action on that front was stymied by legislation in Nashville, but the council did succeed in changing the names of the three downtown city parks associated with the confederacy.

Forrest Park became Health Sciences Park; Jefferson Davis Park became Mississippi River Park; and Memphis Park became the new name of Confederate Park, where a statue of rebel president Davis had been erected in 1964 as an antidote to the civil rights activism of the time.

A renewed burst of activism followed from the murder in 2015 of nine black churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina, by an unregenerate racist with an obvious fetish for the confederate battle flag. That once ubiquitous standard began coming down from flagpoles everywhere, and simultaneously the fig-leaf of states’ rights as a cloak for the confederacy was becoming more and more transparent.

There was new agitation locally for action on the monuments to both Forrest and Davis, but a formal request by the city of Memphis to the state Historical Commission for a waiver permitting relocation of the statues was denied. And in 2016, the legislature further hardened the state’s ad hoc Heritage Protection Act, which already forbade removal of war monuments, extending that protection now to statues of individuals.

This year, with the shadow of Charlottesville looming large, a consensus toward turning the historical page seemed inevitable. Momentum was gathering to force the issue, with even Governor Bill Haslam siding with the city in its desire to remove the offending statuaries.

Whether the governor’s wishes carry any weight will be determined at the forthcoming October meeting of the Historical Commission. — Jackson Baker

We’re History

The Tennessee Historical Commission is a varied bunch.

The 29-member board includes 24 governor-appointees, split equally among the state’s three Grand Divisions. The other five are ex-officio members: the state historian, state archeologist, the Tennessee Commissioner of Environment and Conservation, the state librarian and archivist, and the governor.

Whites outnumber African Americans and other racial minorities on the board. One seat on the commission — one of the eight from West Tennessee — is vacant.

The board typically votes on whether or not a site should be listed on the Federal Register of Historic Places or whether or not to place one of the state’s historic markers. Voting whether to allow Memphis to remove its Forrest statue during a time of national protest over confederate monuments puts the commission in an unaccustomed hot seat.

“[The decision] juxtaposes the valid historic inquiry of how the Civil War was remembered and memorialized at the time the monuments were erected with the modern sensitivities of a significant portion of the local citizenry, which is itself divided ideologically and racially on the propriety of their location and indeed their existence,” says THC board member Sam D. Elliott, a Chattanooga attorney who says local input on the Forrest removal waiver is one of 13 factors the commission will consider when they vote.

Elliott is a board member of the Tennessee Civil War Preservation Association (TCWPA), a group dedicated to protecting Tennessee’s Civil War battlefields. Also on that board are Lee Millar, the outspoken leader of the Memphis chapter of the Sons of Confederate Veterans and Curt Fields, a well-known Ulysses S. Grant impersonator from Collierville.

One of the West Tennessee seats is filled by local history professor, Doug Cupples, who was one of the members of a board created in 2015 to consider re-naming three Memphis parks. Cupples was against it, saying the confederacy was “a significant part of the city’s history,” and noting that Forrest was one of the city’s top historical figures.

Cupples’ suggestion at the time of the re-naming vote was to add monuments to the park to include African-American citizens.

The commission includes, among others, Earnie Bacon, another TCWPA member; Ray Smith, an Oak Ridge historian, Kent Dollar, a Tennessee Technological University history professor who wrote Soldiers of the Cross, Confederate Soldier-Christians and the Impact of the War on their Faith; and Toye Heape, a member of the Native History Association who once sued the state over a road to be built over sacred burial grounds. — TS

Maya Smith

Maya Smith

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Toby Sells

Toby Sells  Greg Cravens

Greg Cravens  JB

JB  Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  Jackson Baker

Jackson Baker