JB

JB

Now you see it, now you don’t.

At some point in mid-year 2012, a solid granite slab-like marker, 13 feet wide and bearing, in bold, black capital letters, the words “FORREST PARK,” appeared on the Union Avenue side of the park near the edge of downtown Memphis.

At some point in the week before Christmas 2012, that immense slab disappeared, leaving a scar in the earth where it had been, hastily covered up with a blanket of fresh-turned grass and earth.

There are mysteries in the case of the granite-sign affair, but two facts seem clear: One is that the sign was apparently purchased and paid for by members of the N.B. Forrest Camp 215 of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, a group devoted to the memory of controversial Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest. Forrest rose from enlisted ranks to become one of the most celebrated military commanders of the Civil War, as well as one of that conflict’s most enduringly controversial figures.

And the other undisputed fact is that George Little, CAO of Memphis city government and the right-hand man of Mayor A C Wharton, ordered the sign uprooted and hauled off to a city storage site, where it now remains.

What remains vague about the affair is how the sign got authorized to be there in the first place. There is no record in city files of such a sign being approved as a marker, said Little, who researched the matter once it was brought to his attention by Shelby County commissioner Walter Bailey, a lawyer who, with his brother D’Army, has long been a leader in local efforts to eradicate all traces of the era in which whites dominated blacks, first by slavery and later by various forms of legal segregation.

On October 12th, Bailey, who had expressed his displeasure to Little about the bold new marker, followed up by sending the CAO a three-part file on the matter.

Part one consisted of the minutes of a July 2005 meeting of the Center City Commission (now the Downtown Memphis Commission), the body charged with making policy recommendations on downtown development. The issue was a proposal, seriously pushed at that meeting by several board members — notably Bailey, then as now a county commissioner, and Barbara Cooper, then as now a state representative — to rename Confederate Park, Jefferson Davis Park, and Forrest Park, and by so doing, purging these downtown public facilities of their connection to the lost cause of the Confederacy.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Part two was a collection of brief materials from the July 2012 newsletter of N.B. Forrest Camp 215. The key portion was a note from a posting member, Brent Dacus of Collierville — “All, we have a new sign for Forrest Park in Memphis. Man is it sharp … Here is the picture” — underneath which was a photograph of the sign, behind which towered the statue of Forrest on horseback.

Part three was a longish monograph by one Tim Bounds. Entitled “Remembering Nathan Bedford Forrest: White Supremacy and the Memphis Monument,” the paper reviewed the Civil War career of Forrest, who, while generally acknowledged to have been a brilliant, brave, and innovative cavalry commander, was stigmatized in Bounds’ view by three facts: Forrest was a slave trader in Memphis before the Civil War; he was alleged, during the war, to have presided over the massacre of black Union troops at Fort Pillow in West Tennessee; and, after the war, he was a co-founder of the Ku Klux Klan.

Bounds makes the case, as his title suggests, that present-day veneration of Forrest, whether in the guise of admiration for his military exploits or in a more general sense, amounts to nothing less than a continued devotion to the concept of white supremacy.

Another sign at Forrest Park touts the N.B. Forrest 215 chapter of the Sons of Confederate Veterans.

But Forrest has his defenders, by no means limited to the members of N.B. Forrest Camp 215. One is the late historian Shelby Foote, author of the acclaimed three-volume history, The Civil War: A Narrative, and a central figure in Ken Burns’ TV documentary The Civil War. There are numerous others, and Forrest Park is by no means the only site where there is a monument to the general. Tennessee alone has upwards of 30 historical markers commemorating Forrest, including a bust in the state capitol building in Nashville. Statues and memorials exist elsewhere as well — in Georgia, Alabama, and presumably other states of the old Confederacy, where Forrest waged and won numerous battles, often against superior troop numbers.

In recent years, however, the champions of Forrest’s historical memory have been fighting a rear-guard action against attacks based on the general’s alleged virulent racism and, in particular, on the three points mentioned above — Forrest’s occupation as slave trader, the accusations of massacre at Fort Pillow, and Forrest’s founding of the Klan.

Forrest’s advocates allege that he was relatively benevolent as a slave trader, declining to separate established black families. They cite historical accounts that challenge reports of a massacre at Fort Pillow or that dispute the general’s involvement in such instances as may have taken place. And they stress that Forrest made efforts to dissociate himself from the Klan once cadres within the organization began to practice systematic violence. They also cite, as even some unchallenged historical accounts do, public moments of chivalry shown by Forrest toward African Americans after the war.

“He wasn’t the vicious character that some people make out,” says Frank Trafford, a member of N.B. Forrest Camp 215, who goes on to say, “Anyhow, that was a different time, and what we’re trying to emphasize is heritage, not hate.”

Trafford points out the fact, not well known by most Memphians, that members of N.B. Forrest Camp 215 have performed numerous maintenance services at Forrest Park over the years, taking care of the statue (which is also the gravesite of Forrest and his wife), tending the lawn, and removing debris.

In addition to the group’s recent donation of the Union Avenue granite marker, now removed, camp members had provided at least one other prominent sign on the park site. This one, a standing two-sided bronze marker, attests to the formation of N.B. Forrest Camp 215 and says that the camp “helped raise funds for the Forrest Equestrian Monument dedicated in this park in 1905, and in 2002 it funded replacement of the weathered gravestones of Forrest and his wife at the Monument.”

Touting the camp’s involvement in other preservationist activities at Confederate Park, Jefferson Davis Park, Elmwood Cemetery, and other sites, the marker, erected in 2004, notes that the camp “continues to lead and provide assistance in projects involving preservation of Confederate history and Southern heritage.”

Trafford recalls being present at that 2005 Center City Commission meeting, at which numerous city and civic officials in addition to Bailey were calling for change in the name and status of Forrest Park, including the commission’s board chairman at the time, Rickey Peete, then still serving on the city council, and Paul Morris, a board member then and now director of the Downtown Memphis Commission, successor to the Center City Commission.

Though it did not become part of the official resolution presented by Walter Bailey, proposals were floating at the time calling for exhuming the remains of Forrest and his wife and transferring them to another location.

“I thought we were done for,” says Trafford, who took heart when resistance to the resolution surfaced from, among others, then state senator Steve Cohen, now congressman from the 9th District. The minutes of the meeting record Cohen’s position, in part: “There have been things that have offended him as a minority, but he has learned to overcome those personal offenses and see things in a bigger light. … He asked for the board to reconsider this issue and not pass it forward, for it will do no good and will only do harm.”

The resolution passed and was transmitted to the city council as a recommendation and to the Chamber of Commerce, the Landmarks Commission, and the Convention & Visitors Bureau for “consultation,” but its momentum had been blunted, and ultimately nothing came of it.

There has been an uneasy quiet on the issue of Forrest Park since, and efforts ebbed to have the bodies of Forrest and his wife removed or to change the park’s name and function, especially after the park was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2009, over opposition by Bailey, state representative G.A. Hardaway, and others.

That nomination to the National Register had been submitted by N.B. Forrest Camp 215, solidifying the camp’s role in helping tend the site. The various issues regarding the park subsided somewhat, a fact acknowledged by Bailey, who told The Commercial Appeal at the time, “I think we’re at a point where until such time as we see some concern by our city leaders, we have to continue to pause,” though he took a shot at “our city leaders” for “being so passive about it.”

But then came the bold new sign on Union Avenue, which Bailey says he regards as “a foot in the water” disturbing the uneasy equilibrium.

Cindy Buchanan, a longtime city employee, served as parks director until her retirement in 2012, and she acknowledges that she had a relationship with members of N.B. Forrest Camp 215 and that camp representatives had asked her permission to allow the new sign.

“I honestly don’t recall what I said to them about that,” Buchanan says.

City CAO George Little

Little, who says he researched the matter “for weeks” at the time of Bailey’s complaint, could find no evidence of any kind, either documentary or anecdotal, that Buchanan or anyone else in city government, including the mayor or the city council, had signed off on the request from N.B. Forrest Camp 215. And, when first contacted by the Flyer about the matter in the week before Christmas, Little said he was undecided concerning two different courses of action: to accept the fact of the sign in place and make the best of things or to remove it as an unauthorized intrusion on the park space.

Little was at pains at that time to dissociate the matter from the past controversies concerning Forrest Park: “To me, it’s a matter of process. We do have processes in city government, and there’s a way to go about making changes in city property. We can’t just allow citizens to put their own signs and monuments up without some kind of official approval.” Moreover, said Little, he had concerns about the “scale” of the sign, which seemed inappropriate. “If we were to approve a new sign, it ought at least to be appropriately sized and designed.”

So it was, he said this week, that “when we had a crew available around Christmastime, I just decided to go ahead and have the sign removed.”

At press time, efforts by the Flyer to reach a spokesperson for N.B. Forrest Camp 215 were unavailing (Trafford. having disclaimed that role for himself), but it is not hard to imagine their reaction to Little’s action, given camp members’ past involvement with the park and their strenuous efforts to maintain its status and condition — not to mention whatever expense they had gone to in purchasing and preparing the vanished sign.

Having contacted various city officials, we also drew a blank, as Little had, in finding someone to own up to having approved the location of the sign. Indeed, efforts to find the responsible party resulted in something of a daisy chain that led back, for purposes of comment, to Little himself.

At one point, city councilman Shea Flinn said he thought approval for the sign might have come from the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, the facility whose campus and buildings adjoin Forrest Park and which, since 2008, has been under contract to the city to manage the property.

“Yes,” Little acknowledges. “We do have contracts with various agencies to manage this or that city property.” But, he says, Forrest Park continued to be owned by the city, and fundamental changes to the property required approval by someone in city government.

Spokespersons for UT confirmed that the university had a contract with the city for upkeep and management of Forrest Park but said the university did not authorize the sign and, in any event, could not make such changes without authorization from city officials.

In any case, it is there no longer, and it remains to be seen whether and to what extent its removal might shake the local firmament.

UPDATE:

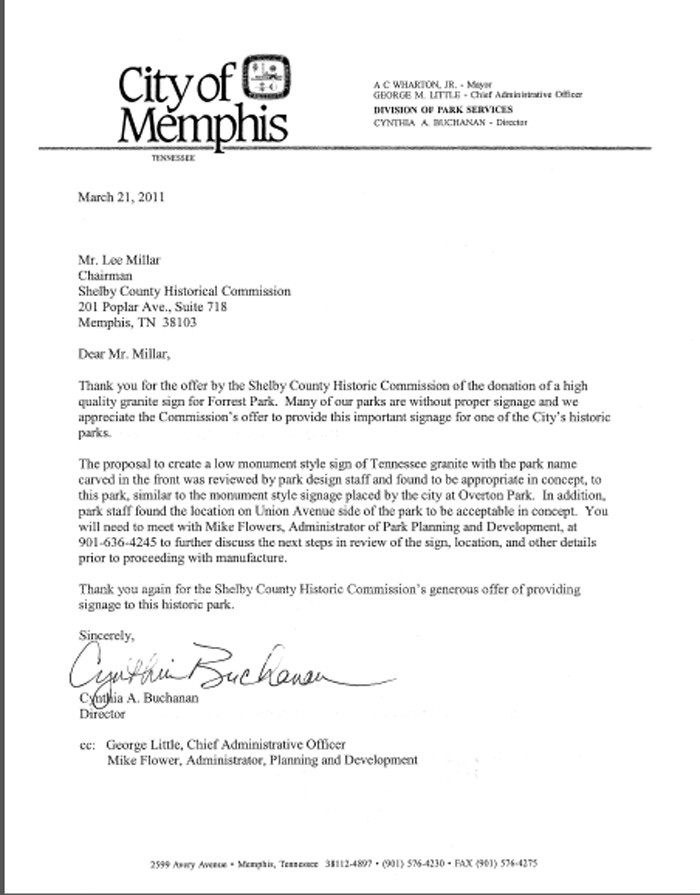

A possible solution to the mystery of the Forrest Park granite sign that was recently removed by city CAO George Little was received, quite literally, at our press time. Lee Millar, an officer of N.B. Forrest Camp 215, sent the Flyer a copy of a letter received by him from Cindy Buchanan, then city parks director.

Dated March 21, 2011, and addressed to Millar, not in his role as a camp officer but to “Lee Millar, Chairman, Shelby County Historical Commission,” the letter from Buchanan says, “We appreciate the commission’s offer to provide this important signage for one of the city’s historic parks.”

Buchanan’s letter further says, “The proposal to create a low monument style sign of Tennessee granite with the park name carved in the front was reviewed by park design staff and found to be appropriate in concept … similar to the monument style signage placed by the city at Overton Park.”

The letter directed Millar to meet with Mike Flowers, administrator of park planning and development to follow through on the construction and installation of the sign. Copies of Buchanan’s letter were apparently sent to both Flowers and Little.

Referring to Little’s recent action in removing the sign as “unauthorized,” Millar said that, upon getting Buchanan’s approval, N.B. Forrest Camp 215 raised funds for the marker and spent some $9,000 for it, plus the cost of installing it.

Buchanan’s 2011 authorizing letter to Millar (addressed to him as a representative of the Tennessee Historical Association).

JB

JB  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks