All That Is

By James Salter

• Knopf, 291 pp., $26.95

James Salter is a curious writer, in both the transitive and intransitive senses of that adjective. Born Horowitz and having become, after West Point, an army, later air force officer — an aviator with combat experience in World War II and Korea — he seems to have reinvented himself in mid-career as an Eastern Seabord aesthete, an out-and-out Wasp.

Having thrown off both his original surname and his military mufti, he apparently lives by two maxims, one of which shows up in interviews and recent nonfiction writings — “Life is just a dream. The only thing real is what is written down,” goes one variant. The other turns up frequently as a kind of leitmotif in the latest literary work by this 88-year-old artist, the novel All That Is, a truly mesmerizing work that reads like, and at some level must be, a roman a clef.

“Whatever you believed would happen was what happened,” is the way Salter’s second dominant maxim is formulated on its last appearance in the novel — representing, in this case, the lifetime credo of Beatrice, a dying Alzheimer’s victim who is mother to the novel’s chief protagonist, publishing-house editor Philip Bowman. In her case, it’s a concept about the afterlife. In Bowman’s, it’s a counterpoint to the circumstances, each one surprising but somehow inevitable, that alternately light up and darken a life experienced on both shores of the Atlantic.

The book is mainly a chronicle of Bowman’s life from naval service in the Pacific theater to some indeterminate point of seniority in the book world, comprising along the way his romantic triumphs and cuckoldings, his successes and mischances, his nobility and caddishness, his shrewdness and naiveté, and his place in the chain of being as a unique kind of Everyman.

Other characters also figure — some of them in stand-alone vignettes that slice through the heart in the abrupt, lumpen-tragic manner of early Hemingway or early Raymond Carver, as when an editing comrade of Bowman’s bids wife and child adieu on a train ride which ends with them asphyxiated from the fumes of a fire en route. Or when a discarded old flame of Bowman’s consumes an entire bottle of wine at a solitary dinner at an elegant New York restaurant and makes a scene when she is not allowed to buy another. Or the failed painter who has to ask his estranged ex-wife for permission to have an affair. But there are numerous light moments as well, and joys — everything, it would seem, that belongs to the human comedy. And Salter is surely without peer in his ability to render, precisely and with considerable erotic charge, sexual encounters of every sort imaginable through no means other than simple everyday language.

Nothing in fact is overstated in a novel which, despite its somewhat Proustian flavor, never becomes sentimental and maintains an energy, akin to static electricity, that can jolt one out of nowhere amid what would seem to be a commonplace event.

All That Is is extraordinary work from an elder literary statesman, author of screenplays, travel books, and story collections, along with several earlier novels that have been well regarded, especially by other writers. — Jackson Baker

My Education

By Susan ChoiViking, • 296 pp., $26.95

Susan Choi’s My Education begins as most novels of academia do: with lengthy explications of petty departmental politics, insider jokes about postmodern esoterica, persistent evocations of a college-town milieu, and gently self-denigrating jabs about the usefulness of a liberal arts degree in the real world. This is well-trod territory in fiction, not least because universities are the leading employers of fiction writers. In other words, the set-up is deeply familiar.

Regina Gottlieb, a first-year grad student in the poetry department of a tony university in upstate New York (and it’s always upstate New York in these books), finds herself obsessed with a professor named Nicholas Brodeur, a Chaucer scholar with a reputation for seducing/harassing his female students. You can almost see the narrative dominoes falling from the first pages: Nicholas is all but estranged from his wife, and the addition of a new baby will surely prompt an urge for escape, obviously into the arms of a young woman who believes — naively, selfishly, academically — that love levels all obstacles in its path.

Soon, however, Choi introduces a twist that neatly and completely upends the conventions of the academic novel. It’s too crucial to spoil in a review, and it happens so suddenly that it may send the reader skimming over those first 60-odd pages for hints of this new turn of events. Those hints are there, planted cleverly and carefully by Choi. Not only is this the action of a consistent and impulsive character (Regina doesn’t kill anybody, if that’s what you’re thinking), but it renders the characters newly vibrant, the setting more novel, the comedy more inventive, and the plot more devious.

Choi’s writing can be convoluted, as she peppers her sentences with asides, interjections, reminders, qualifications, feints, descriptors, and assorted prose noise. And yet, there is a crucial purpose to this approach. Just as she did so well in her 2003 novel American Woman, loosely based on the Patty Hearst kidnapping, Choi portrays the world from a particular point of view, in this case a narrator who may be trying too hard to lend her past a romantic sheen. Throughout the novel’s winding sentences as well as its winding plot, Regina grows increasingly fascinating in her naiveté to become a vivid and compelling study in innocence regarding itself as worldly wisdom. — Stephen Deusner

How Should a Person Be?

By Sheila Heti • Picador, 320 pp., $16 (paper)

Sheila Heti’s second novel is “part literary novel, part self-help manual,” a collection of musings, conversations, and questions on the mire of self-discovery and one 21st-century artist’s meandering search for greatness.

Surrounded by her equally restive artist friends and grappling with a dreaded assignment to write “a play about women,” Sheila exits a failed marriage and falls headlong into the search for purpose and a sense of worth. “How should a person be?” she asks. “You can admire anyone for being themselves. Responsibility looks so good on Misha, and irresponsibility looks so good on Margaux. How could I know which would look best on me?”

Sheila’s problems are at once familiar to the reader and unique to the author, and as such, they will have you rolling your eyes at her self-indulgence on one page and nodding at her insight on the next. Compared by many critics to Lena Dunham’s HBO series Girls, How Should a Person Be? shares Dunham’s propensity for navel-gazing and raw sexual relationships, which won’t appeal to everyone.

Nor will everyone identify with Sheila’s desperate, often humorous quest for fame and recognition. (“I don’t want anything to change, except to be as famous as one can be, but without changing anything. Everyone would know in their hearts that I am the most famous person alive — but not talk about it too much.”) But chances are, there is something in her story that will resonate with every reader, as Heti’s honest rendition of some of life’s most humbling truths challenges the novel as we know it. — Hannah Sayle

The Ocean at the End of the Lane

By Neil Gaiman • William Morrow, 181 pp., $25.99

Neil Gaiman’s newest novel, The Ocean at the End of the Lane, is being billed as the fantasy author’s return to adult fiction, following eight years of young-adult and children’s books and comics. The highlight of that period was the 2009 Newbery-winning The Graveyard Book.

The marketing of The Ocean at the End of the Lane is both misleading and on the nose. Thematically, the book is about children and what makes them different from adults. Some of the book’s thoughts and extrapolations on the premise are well-worn in the fantasy genre — adults are just children who have forgotten the magic of their youth — but Gaiman finds clever ways to restate them.

The book’s framing device has an unnamed man in his 30s returning to his childhood home in the English countryside. He visits the home of one of his neighbors, the Hempstocks — 11-year-old Lettie was his best friend when he was 7. She claimed then that the old pond by her house was an ocean. Sitting beside it now as an adult, the narrator suddenly remembers a set of fantastical events from his youth, including epic showdowns with monsters both magical and, more terrifying, familial.

Gaiman’s slim tome about coming-of-age reminded me of Karen Russell’s brilliant Swamplandia!. When “real life was too hard or too inflexible,” Gaiman’s narrator escapes into children’s adventure books, where kids are always saving the adults from dangers the latter can’t see. It’s a lesson he struggles to learn. Placing too much trust in adults, Lettie instructs the boy: “Outside, [grown-ups are] big and thoughtless and they always know what they’re doing. Inside, they look just like they always have. Like they did when they were your age. The truth is, there aren’t any grown-ups.”

Gaiman’s body of work rejects a clear demarcation between age-oriented fictions. As the narrator describes myths in The Ocean at the End of the Lane: “They weren’t adult stories and they weren’t children’s stories. They were better than that. They just were.” — Greg Akers

Forty-One False Starts: Essays on Artists and Writers

By Janet Malcolm • Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 298 pp., $27

In a fragment about the impossibility of writing autobiography at the end of Forty-One False Starts, Janet Malcolm says, “I cannot write about myself as I write about the people I have written about as a journalist.” To which her longtime readers will reply (rather loudly), “Of course not, because you’re in the stories you write about people as a journalist.”

Malcolm is an astute practitioner of me-based journalism, a genre that dominates half of the essays in this new collection, the other half being reviews involving books, art exhibitions and their catalogs, and extensions of those forms into critical biography. Malcolm is smarter than most of her readers (I mean objectively; her habitual stance is skeptical and self-deprecating), and her incisive prose, thorough cultural knowledge, and rich background of allusion could induce most writers to throw down their pens. Reading Malcolm on J.D. Salinger or Edith Wharton or the Bloomsbury group or the photographers Edward Weston and Thomas Struth, we feel privileged and elevated, because she expects us to have read everything that she has read — and it seems to be everything — and to follow the precise yet quite personal line of her reasoning. The secret thrill in reading Malcolm is the indelible arc of her merciless observation, sense of physical and psychological detail, and the razor-sharp sarcasm buried in her cool, insouciant narrative.

The book’s centerfold is a 76-page essay, published in The New Yorker in 1986, about the esoteric machinations and rivalries surrounding Artforum magazine, its editors and writers and the artists it promoted. From our perspective, Malcolm might as well be writing about Hogarth and his circle in the 18th century — there’s nothing deader than 35-year-old turf-wars — but even now we take guilty pleasure in her clarity and slyness, her penetrating wit and her thoroughbred air of being the best-prepared girl in the class. — Fredric Koeppel

The Guns at Last Light: The War in Western Europe, 1944-1945

By Rick Atkinson • Henry Holt, pp., 896 pp., $22.75

Rick Atkinson is the Shelby Foote of World War II. The Guns at Last Light is the final book in his trilogy of the liberation of Europe beginning with An Army at Dawn (North Africa), published in 2002, and The Day of Battle (Italy), published in 2007.

How fortunate we are to have such a skillful writer/historian/reporter devote two decades of his life to such work. Children now in elementary school are the last generation that will be able to say they knew men and women who served in the armed forces in World War II — as remarkable as finding someone today who met a man who fought at Gettysburg or Shiloh.

This volume begins with the Normandy invasion on June 6, 1944, and ends with the German surrender to Dwight Eisenhower and the Americans in Reims on May 7, 1945. While the German generals stalled, Eisenhower fretted and tried to read pulp westerns. “Terrible,” Eisenhower wrote. “I could write better ones, left-handed.”

Atkinson, a former Pulitzer Prize-winning writer for The Washington Post, adds such delicious details to every page, driving forward a narrative that might otherwise be an exhausting chronicle of death and annihilation.

Especially memorable are war correspondent Ernie Pyle, battle-fatigued as any GI but able to write some 700,000 words about Europe before he was killed in the Pacific eight months later; Ernest Hemingway, leading his personal band of French fighters into Paris; Dietrich von Choltitz, who stalled Hitler with lies and evasions and saved much of Paris before surrendering the city; and imperious Charles de Gaulle, called “Deux Metres” for his metric height by Americans and an “obstructionist saboteur” by Winston Churchill, who couldn’t stand him.

As in the preceding volumes, Atkinson sets the stage for The Guns at Last Light with a long prologue that includes some of his best writing.

The average GI was 26 years old, stood five feet eight inches tall, weighed 144 pounds, had not finished high school, and earned $50 a month, or $96 if he made staff sergeant. By 1944, however, nearly half of American troops arriving to fight in Europe would be teenagers. This is their incredible story. — John Branston

Dirty Wars: The World Is a Battlefield

By Jeremy Scahill • Nation Books, 680 pp., $29.99

Dirty Wars, the doorstop-size tome from ubiquitous celebrity reporter Jeremy Scahill, promised much to anyone who wanted to see how the ideas of Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld played out from a military-operations standpoint. But readers, like the neoconservatives who relentlessly pushed the U.S. into a ground war in Iraq after 9/11, got more than they bargained for.

Scahill details Rumsfeld’s machinations as he established the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC), a pet special-forces project assuming that any checks and balances within the intelligence community, the Pentagon, or the State Department should be avoided or eliminated. That narrative is interwoven with the story Anwar al-Awlaki, a Muslim American imam who embraced his role as an apologist for Islam following 9/11 but whose treatment by the U.S. government radicalized him to the point that he was imprisoned and eventually assassinated, as was his son, by the U.S. government.

These are two fascinating narratives that need to be told. The book succeeds on its prodigious sourcing and by relentlessly documenting its source material. Think of it as a compendium of research on the matter. But put it next to your unredacted copy of the Pentagon Papers. This is not casual reading, and that is where Scahill disappoints. This should not be entertainment, but there is plenty of middle ground to occupy. He fails to pull back and add context. Details never let up, and the sensation is akin to literary waterboarding.

Compared to Barton Gellman’s The Angler, which chose three episodes around which to explain Cheney’s legal tactics for the executive branch, Dirty Wars is a failure of editing. But for those of us who must know, there are harrowing, firsthand accounts off all that went wrong: from conventional army commanders aghast to find JSOC troops killing civilians and taking prisoners in their theater to the secret torture facilities in Saddam Hussein’s abandoned palaces and the killing of U.S. citizens based on improperly vetted intelligence. Sadly, this is essential U.S. history enshrouded in an almost unreadable book. — Joe Boone

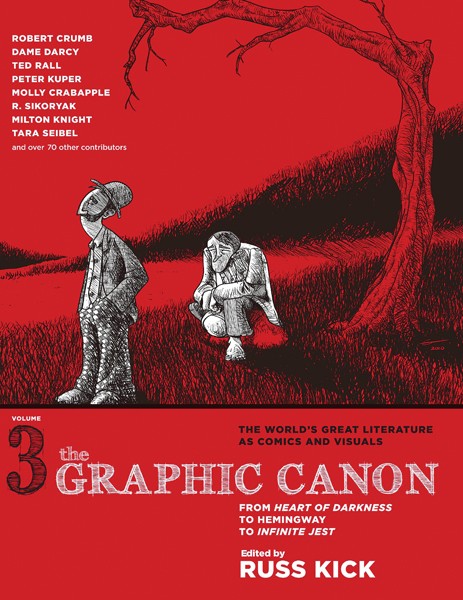

The Graphic Canon, Vol. 3: From Heart of Darkness to Hemingway to Infinite Jest

Edited by Russ Kick • Seven Stories Press, 564 pp., $44.95 (paper)

Editor Russ Kick has described his big books of illustrated excerpts and abridgments as a graphic answer to the Norton Anthology and as a tool designed to encourage interested parties to dive a little deeper into the classics. In an interview with the Memphis Flyer prior to the release of Volume 1 of the three-part series collectively called The Graphic Canon, he also called that volume a “self-contained literary/artistic work” and an “end in itself.” All the descriptions fit, but none completely does justice to these beautiful collections.

The first, 500-page volume began with a Babylonian myth and ended in 1782 with Choderlos de Laclos’ Dangerous Liaisons and included versions of the Iliad, the Odyssey, Beowulf, the Old and New Testaments of the Bible, the Tao Te Ching, Dante, Shakespeare, Milton, and dozens of other literary A-listers.

Volume 2 opened with “Kubla Kahn,” closed with The Picture of Dorian Gray, and included works by Jane Austen, the Brontes, William Blake, and Herman Melville. The artists who’ve interpreted the titles range from underground pioneer R. Crumb, to cranky cartoonist Ted Rall, to Will Eisner.

The Graphic Canon, Vol. 3 is perhaps the most ambitious installment yet. It’s taken David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest (at more than 1,000 pages), but Kick manages to cover that, as well as works by Joseph Conrad, James Joyce, Frank Baum, and Ernest Hemingway.

Not every piece here gets its due, obviously. Take away the opening essay and readers would have no idea what Infinite Jest is about. The single-image summation of 1984 provides only slightly more information, and Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot deserves more than one cartoon of bums under a tree. Considering the brevity of Raymond Carver’s stories, the superficial montage standing in for Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love is almost criminally insufficient. Still, the joys here far outnumber the disappointments.

Have you ever considered what Kafka’s the Metamorphosis might look like as remained by Charles Schulz? Artist R. Sikoryak has, and it’s brilliant. So is R. Crumb’s French-language run-through of Jean-Paul Sartre’s Nausea and Onsmith’s wordless interpretation of J.G. Ballard’s Crash.

Brevity is a mighty tool here when embraced and used as a tool for comment. This is best illustrated by Lisa Brown’s three-panel review of E.M. Forster’s A Room With a View, which is rendered in three sentences, with accompanying images: “George is unconventional”; “Cecil is a BORE”: “How to choose?” — Chris Davis

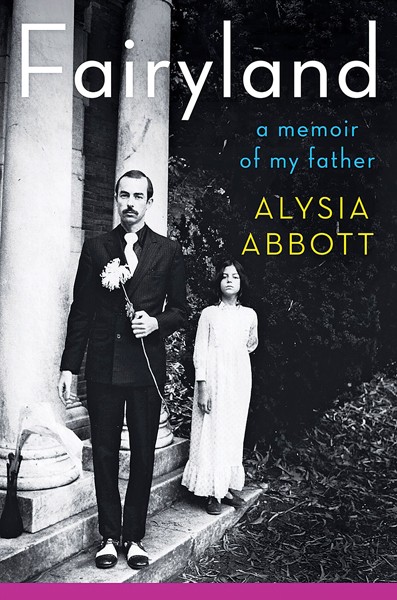

Fairyland: A Memoir of My Father

By Alysia Abbott • W.W. Norton, 352 pp., $25.95

For many, San Francisco in the late 1970s and early ’80s was a frightening place to be. The iconic hippies, who had so captured the world’s attention a decade earlier, faded into the background as heroin replaced pot as the drug of choice for the city’s disenfranchised youth. The spirit of peaceful activism quickly turned to unexpected mayhem in the famous Haight-Ashbury neighborhood of the city, where many public parks were abandoned by families and became littered with syringes. Most devastatingly, a generation of gay men, who had flocked to the city to escape discrimination and form their own community of acceptance, began dying at an alarming rate of a mysterious illness, so many that “whole phone books had to be tossed” in their wake.

This is the San Francisco of Alysia Abbott’s childhood, but in Fairyland: A Memoir of My Father, the writer tells a different story of life in the city at the Golden Gate, a story that is poignant, touching — and highly unconventional.

After the sudden death of his wife in 1973, Steve Abbott moved his then 2-year-old daughter Alysia to San Francisco so he could pursue a life as a poet and cartoonist. Living in a new city as single father of a small child would be tough on anyone, but Steve’s life was also complicated by the fact that he had recently come out as a gay man himself and was trying to find his own voice, both through his poetry and in San Francisco’s vibrant gay scene.

Reconstructing her father’s life through the letters, poems, and meticulous journals Steve left for his daughter after his death of AIDS in 1993, Alysia Abbott beautifully writes of a childhood that could have single-handedly fueled one of Anita Bryant’s anti-gay crusades. She details the numerous men who came in and out of her father’s life, his struggles with addiction, and the times he left her hungry and unsupervised while he was out cruising bars. But despite his flaws, this is not a memoir of a wretched childhood. The “fairyland” of the book’s title is not one of gay excess but of a magical (and sometimes heartbreaking) relationship between a father and daughter.

“When I remember my dad now, I mostly remember his innocence,” Abbot writes. “He burned easily in the sun, so he generally avoided it.”

In the end, it is not the sun that finally burns her father, along with almost all of his friends. The final pages of Fairyland detailing his death are quietly wrenching, but in Abbott’s telling, they become a moving testament of a father’s love from the daughter who loved him endlessly. — Kelly Robinson

Speaking Of: Skyy

April Blair — better known by her pen name, Skyy — had no idea she was even writing a book six years ago when she wrote the draft of her first book, Choices. She was just writing to combat depression, but after a friend read the manuscript, that friend convinced Blair to publish. This past June, Blair released Full Circle, the fourth and final book in her “Choices” fiction series. (The second and third books are titled Consequences and Crossroads.)

The books follow the lives of four women navigating lesbian life at a fictional Memphis college. At the center of the story are Lena and Denise, a pair of roommates whose relationship progresses beyond friendship but not without a cost. Lena was engaged to Brandon, star of the men’s basketball team, until Denise shakes up Lena’s world. The Flyer recently spoke with “Skyy” about her pen name, her fans, and her future. — Bianca Phillips

The Flyer: So, a friend convinced you to publish?

April Blair: That friend was sitting at my computer, and I asked her what she was doing. She said, “Reading this book you wrote. This is even better than the last Eric Jerome Dickey book I read. You should do something with it.” I started researching how to get published, and I came across an independent lesbian book publisher called King’s Crossing.

Has King’s Crossing published all your books?

They published the first two, and they ended up going out of business. But by then, I had been featured on the Michael Baisden radio show, and my books had taken off. Carl Weber, who owns Urban Books, an imprint of Kensington, then wanted my books. He’d been selling them in his bookstores, and they were flying off the shelves.

Where does the pen name Skyy come from?

I originally started calling myself Skyy, because I have a tendency to daydream. In the gay community, if you join gay houses or families, they give you your own name. So I said I’d be Skyy.

Are the books written for the lesbian community, or do they have a broader appeal?

They were originally written for the lesbian community, but after I did The Michael Baisden Show, I learned that I had a lot of straight readers — men and women. The characters almost become gender-neutral. I think that’s why the books appeal to so many. You don’t love these people, because they’re gay. You love these people because of who they are.

What’s next for you?

One of the main things my fans want is a movie or TV series based on the books. I hope that’s coming soon. The geek in me wants to write sci-fi books. And I’d like to assist other lesbian and gay authors to get their work out there and be seen.

Mo’ Meta Blues: The World According to Questlove

By Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson • Grand Central Publishing, 288 pp., $26

Mo’ Meta Blues by Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson, the eccentric drummer for the Grammy Award-winning hip-hop band the Roots, takes readers through some of his most memorable musical experiences, from adolescence on up. The book, co-authored with New Yorker editor Ben Greenman, also provides readers with an in-depth look at all the things that contributed to making Questlove the musical icon he is today. It starts with his upbringing in West Philadelphia.

The product of doo-wop-singing parents, Questlove picked up his first set of drumsticks at the tender age of 2. A few years later, he was already touring the world with his parents as their band’s drummer. This leads to his enjoying rare experiences — from meeting rock-and-roll idols such as Kiss to roller-skating with legendary pop artist Prince.

Aside from Questlove reliving different run-ins with celebrities, there are segments throughout the book titled “Quest Loves Records,” which highlight the music that had a significant effect on him — music such as the Sugar Hill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” and Prince’s 1999 and Michael Jackson’s Thriller.

Mo Meta’ Blues also includes footnotes by Richard Nichols, producer and co-manager for the Roots, who provides his personal opinion on the music-related matters that Questlove reminisces about.

Overall, Mo Meta’ Blues turns out to be an entertaining read for anyone wanting a better understanding of how Questlove developed his passion for listening to, collecting, and creating music. And while you’re at, you can read a personal account on how the Roots were formed and how they were catapulted into being one of the biggest hip-hop groups ever. — Louis Goggans

Steal the Menu: A Memoir of Forty Years in Food

By Raymond Sokolov • Knopf, 229 pp., $25.95

It would have been an unenviable task for any soul, but it was Raymond Sokolov who succeeded the legendary and trailblazing Craig Claiborne as The New York Times’ food editor. But, for Sokolov, the Times job was but a brief stop in what turned out to be a 40-year career in journalism, much of it writing about food. As he recounts in his memoir Steal the Menu, Sokolov — Ivy League-educated with a focus on the classics — witnessed in that large swath of time everything from the rise of nouvelle cuisine to tackier pursuits of the now-beleaguered Paula Deen.

The title comes from a bit of advice Claiborne gave to Sokolov on the pilloried item near-essential to reviewing restaurants in a pre-internet age. As it happened, Sokolov never felt fully comfortable in his role at the Times and his editor Abe Rosenthal. Rosenthal was never fully comfortable with him and fired Sokolov a little more than two years in.

The liveliest moments of Steal the Menu come in the peeks behind the curtain: the state-of-the-art test kitchen at the Times and its role in unmasking a subpar recipe for Tricia Nixon’s wedding cake; the $100,000 for travel and food expenses billed to The Wall Street Journal, to name just two. More trying are the veering-into-the-pedantic sections in which Sokolov attempts to set the record straight on nouvelle cuisine or discusses his interest in rare Homeric vocabulary in Theocritus. (Seriously!).

Sokolov’s academic half and journalistic half were finally combined during his time at Natural History magazine, where he wrote a series of stories focusing on local foodways. His expansion into this sort of culinary anthropology eventually leads to barbecue, and with that Memphis gets a one-paragraph cameo in Steal the Menu, a section of which is included here and presented without comment (because … where to start?):

“At the huge festival on the banks of the Mississippi called Memphis in May, I got sunburned and burned in general at the insulting scam, in which dozens of ‘famous’ barbecue teams compete with their ‘famous’ sauces and meats from their portable pits, but the thousands of ticket holders rarely get a taste of that ‘famous’ meat, which is not for sale but prepared for the elite palates of the judges alone.” — Susan Ellis

The Complete Short Stories of James Purdy

Liveright/W.W. Norton, • 753 pp., $35

Sad, distressed, lonely, angry, defenseless: Those are a few of the words John Waters uses to describe the characters one meets in the stories of James Purdy. Combine those stories into a single volume, and Waters calls the collected work “a ten-pound box of poison chocolates” — one to keep by your bedside and dip into for a rotten night’s sleep.

The publisher calls the volume simply The Complete Short Stories of James Purdy — close to 60 stories in all to cover the career of a writer who died in 2009 and whose controversial work was praised, as the book’s jacket reminds us, by Edward Albee, Lillian Hellman, Dorothy Parker, Dame Edith Sitwell. Gore Vidal, too, who called Purdy “an authentic American genius.” As Waters writes in his introduction to The Complete Short Stories, Purdy has “been dead center in the black little hearts of provocateur-hungry readers like myself right from the beginning.”

Where to begin, though, if you’re new to Purdy’s dark, hothouse world of losers, alcoholics, addicts, inverts, drifters, and world-class outcasts? Your best bet is to draw from a random sample of the stories, but start with “63: Dream Palace” (published in 1956), which at 60 pages is less a short story and more a novelette. There, on 63rd Street, you’ll meet Fenton Riddleway and his younger brother Claire. Fenton is the healthier, handsomer one with no income and seemingly no wish for one. Claire’s a shut-in and, mentally speaking, pretty out of it.

The brothers have arrived in the big city (what city? it’s never clear) from West Virginia, and a friend has arranged for them to inhabit an empty, dilapidated boarding house. How do the two spend their days? Claire: by sleeping on a cot in one of the house’s bug-infested downstairs rooms. Fenton: by dropping into bars and coffee shops and the All Night Theater, where, if the zombies inside aren’t groping for newcomers in the dark, they’re staring blankly into space. But when we first meet Fenton, he’s passing time in a city park, and he’s lost among the lovelorn and sex-starved, until he’s found by Parkhearst Cratty, who’s married to a woman named Belle but spends his evenings in the company of a gin-swilling grande dame named Grainger and a black jazz combo.

Will Fenton fall for the attention (booze, fine clothes) lavished on him by Parkhearst? Will an excitable young man named Bruno survive a beating after Fenton blacks out on some killer weed? And what of poor Claire? At the end of “63: Dream Palace,” there’s room for him in the boarding-house attic, a victim of some nasty business thanks to his loving brother, who finishes off Claire’s fate with a kiss and a tenderly delivered directive: “Up we go then, motherfucker.”

The keyword there? And a key to the unsavory but redemptive quality of James Purdy’s best writing? That surprise word: “tenderly.” — Leonard Gill