Every Experience Counts

Courtney Barnett on her music, her label, and life on the road

Courtney Barnett is getting ready to board a plane somewhere on the West Coast when her manager hands her the phone. She sounds tired and in a bit of a haze, which is understandable, considering she’s been on the road almost nonstop for the past two years.

In the time that’s led up to our phone call, Barnett has gone from one of Australian indie rock’s best-kept secrets to a Grammy-nominated household name. Her deadpan vocal delivery and witty lyrics have pushed her to the forefront of a modern music movement that sits somewhere in between mainstream rock and the type of stuff you hear playing at Urban Outfitters. But there’s something more intelligent and authentic about Barnett’s music, something that sets her apart from the pack.

Growing up in Pittwater, Australia — a port town about an hour outside of Sydney — gave Barnett her small-town charm and provided endless experiences that would later serve as song fodder.

“[Pittwater] was far up from town, so that probably made my imagination run a little bit more. It was kind of harder to do things with friends after school and stuff,” Barnett explains.

“We were around lots of bush, and me and my brother would run around a lot in the water. We were very outdoorsy. I reckon that helped start my creativity a little bit better than sitting in front of the TV would have.”

Barnett sharpened her chops in the Melbourne grunge band Rapid Transit and played with psych-rockers Immigrant Union as well as lead guitar on her girlfriend Jen Cloher’s album, In Blood Memory. But even though she’s a gifted guitarist, Barnett is most known for her lyrics. “Pedestrian at Best,” the breakout hit from 2015’s Sometimes I Sit and Think, and Sometimes I Just Sit, comes across like a smarter “Smells Like Teen Spirit” for a new generation of alt-teens. Her greatest attribute as a songwriter is how effortlessly she seems to spit out sharp lyrics.

“I guess I write lots of different stuff,” she says. “I do a lot of journal writing, and I write short stories that don’t turn into anything. I don’t think I’m as disciplined as I could be or should be. I don’t really have a solid writing schedule.”

When it comes to writing lyrics, there isn’t a set formula in place either, but she does cite Jonathan Richman, Patti Smith, and Leonard Cohen as some of her favorite lyricists. When I ask whether the lyrics or the song comes first, Barnett says, “It depends on the situation. It’s different every time. I let my mind wander under some kind of subconscious stream, and I see what comes out. Sometimes I start with a song title, and that gives it a direction; other times I start with a narrative. I always have to be singing about something though; songs about nothing piss me off.”

Sometimes I Sit and Think, and Sometimes I Just Sit and 2013’s double EP, A Sea of Split Peas, were both released on Milk! Records, a small label founded by Barnett and Cloher in their living room. The label remains fiercely indie since Barnett has risen as a high-profile songwriter, and she laughs when I ask if the record label has become a subsidiary of something bigger.

“It’s pretty small,” she says. “We run it ourselves and fund it ourselves, and we work with about seven bands. Me and Jen and a couple of my friends do it. I think it’s like the best thing in the world. I get to release my music and my art and my friends’ art. I don’t have any interests in forfeiting those things for money or for success,” she adds. “I have enough money to do what I want to do. It’s comfortable and lets me be artistic.”

Some of Barnett’s best songs are about the more mundane aspects of existence. “Depreston” sounds like a classic love song on the surface, until you dig deeper and realize that she just made you have feelings about a percolator that makes great lattes. With the ability to romanticize inanimate objects, you’d think that the road could take its toll, especially on someone who enjoys the little things that come with a stable lifestyle. Barnett doesn’t see it that way.

“We’ve been touring nonstop for the past two years. It has ups and downs, but I’m traveling the world, playing my songs to people, and that’s kind of really good,” Barnett says.

“It’s a weird life. We’ve become a weird family because we spend more time with each other than we do with our partners. I’d never thought I’d have enough money to travel outside of Australia. I always assumed I’d never get to leave. And now we’ve traveled the whole world.”

Barnett is getting ready to board that plane when I ask her in what setting she most prefers performing her music. This is an artist whose music works as well in a DIY basement venue as it does being blasted out of festival speakers at Coachella.

“I think my favorite kind of show is a tiny club full of people with their hands on the stage. But we are lucky that we’ve been able to do both, because fests are just as fun. We played this beautiful theater last night, and that was amazing, but you’re on stage to play these songs to people no matter where you are, and that’s pretty fucking cool.”

Perhaps that’s the most compelling thing about Barnett. Whether she wanted to or not, she’s become modern rock-and-roll’s great equalizer, taking her brand of lyrically driven indie music and putting it in front of anyone who will listen.

If 2015 was any indication, there are millions of people who are doing just that. — Chris Shaw

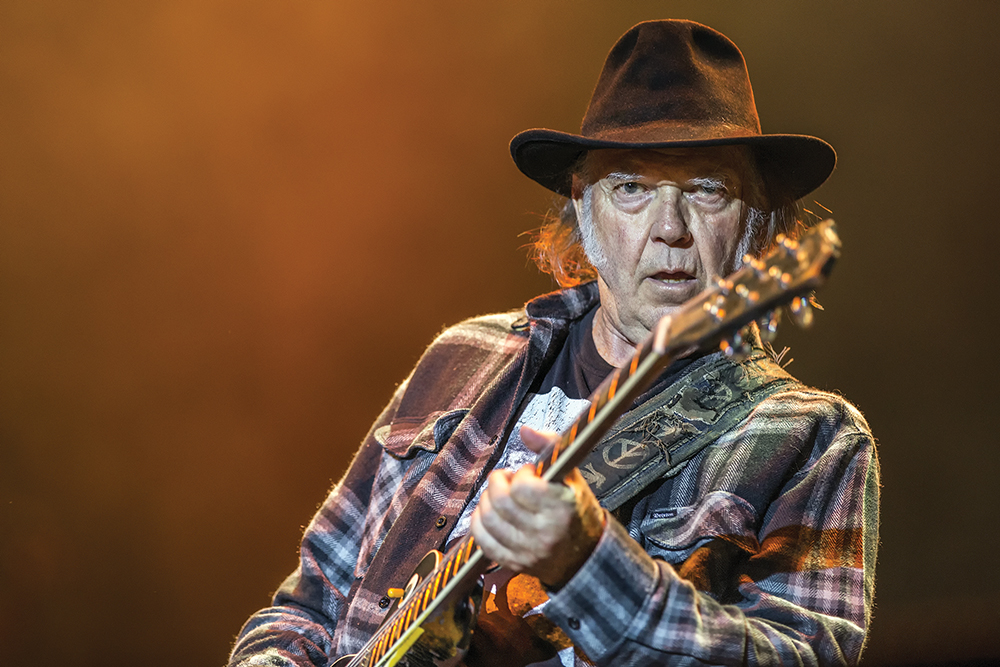

Neil Young & Promise of the Real

Vampire Blues

Thoughts on two classic Neil Young albums

With a legendary career that’s lasted nearly 50 years, we could dedicate this entire issue of the Flyer to Neil Young, and there would still be plenty more of his story to tell. The Canadian-born Young is one of the greatest songwriters in rock-and-roll history, and his signature vocal style is one of the most recognizable in music. Like the Grateful Dead or the Rolling Stones, Young has a following that’s as devout as they come, meaning that you don’t often hear, “Yeah, I only like a couple of his songs” when the conversation is about ol’ Neil.

While other popular artists have had to reinvent themselves multiple times to stay relevant in the mainstream, Young has stuck to his guns as a left-field songwriter. That’s not to say the man’s perfect (The Shocking Pinks, anyone?), but he is reliable. Even that album has one of the best recorded versions of his hit “Wonderin’.” Young also has some interesting Memphis ties, having toured with Booker T. and the M.G.’s as his backing band in 1993.

Young’s long career has already been written about, dissected, and criticized at great length, so I decided to focus on two Neil Young albums that changed my perception of what classic rock could be. Here’s hoping he plays anything off either of these records when he headlines Beale Street Music Fest Friday night.

On the Beach (Reprise Records, 1974)

If you ever find yourself planning a play-list for a road trip, this album needs to be in your rotation. On the Beach perfectly captures Young’s ability to write personal lyrics and his willingness to talk shit to those who’ve wronged him in some way. “Walk On,” the first song on the album, immediately addresses his critics or past friendships that have turned sour. There is plenty of lyrical gold on this album, from the biting lines of “Revolution Blues” (most likely inspired by his visits with Charles Manson) to the prophetic lines on “For the Turnstiles.”

This is classic “negative” Neil Young, but the songwriting and guitar playing is so mesmerizing that you almost forget that these are, for the most part, sad or angry songs. While On the Beach wasn’t as commercially successful as Harvest or After the Gold Rush, the record is widely considered one of his best albums by fans and critics, even if it wasn’t widely available until decades after it was released.

Zuma (Reprise records, 1975)

Deciding to rank this album below On the Beach was difficult, but since I heard On the Beach first, I suppose it’s only fair to call this my second-favorite Neil Young record. The album artwork has a vibe of “this is so ugly it must be good” going on, but what’s inside is pure gold. Album opener “Don’t Cry No Tears” is an absolute killer; the lyrics tell a gut-wrenching tale of a woman who has moved on. The song is as depressing as they come, but maybe that’s the best thing about this era of Young’s music — he made being depressed and negative acceptable, cool, and perhaps most important, marketable.

Most modern, politically correct music writers would probably classify Zuma track “Stupid Girl” as sexist, but some of the best rock-and-roll has always been controversial (See “Under My Thumb” by the Rolling Stones or “All This and More” by the Dead Boys). And no, I’m not comparing Neil Young to the Dead Boys, but the point is that you don’t have to be in a great mood to write a great song. — Chris Shaw

Andrea Morales

Andrea Morales

Julien Baker

New Hometown Hero

Julien Baker bridges her DIY roots with a critically acclaimed music career on the rise.

Julien Baker is on her way to Indianapolis, Indiana, where she will begin a 13-day tour that ends at Beale Street Music Festival. She’s been reading a lot. One book is about straight-edge hardcore. Another is a historical analysis of emo, Nothing Feels Good — fitting for a musician whose Instagram bio reads, “Sad songs make me feel better.” She’s also reading articles about punk. On April 29th, she’ll open Beale Street Music Festival on the same stage where Neil Young will later headline.

Just a few years ago, Baker played most of her shows in a suburban living room in Memphis’ Smithseven House. Now, she’s navigating a transition from her DIY roots to a critically acclaimed music career whose trajectory seemingly has no ceiling.

“In an interview Aaron Weiss (of MewithoutYou) did with BadChristian, he said, ‘I feel like I’m always striving, and I’m always doing it wrong,'” Baker says. “But I’m obsessed with striving.'”

“I feel like I mess up a lot. The existential pressure, as the opportunities grow and I get to do more things, like play bigger cap venues, that increases the level to which I have to be very intentional about how I am using these opportunities. Am I just letting them fall on me — or employing them for some greater cause?”

I first met Baker at a now-defunct church called Veritas, which occupied a room at the Butcher Shop on Germantown Parkway. She was 14 years old and not much shorter than she stands today. “Celtic Thunder,” hollered worship leader Charlie Shaw, calling her to the impromptu stage. Between her long red hair and her skill set on the mandolin, the nickname stuck.

After church ended that day, Baker told me she was starting a band called the Star Killers with some Arlington High School friends. They later changed their named to Forrister, and she still plays with them. At the time, I played in a band called Wicker that frequented the Skate Park of Memphis. Created by Smithseven Records founder Brian Vernon, it served as the house band for a nonprofit label that gave most of its money to charity.

The skate park was Baker’s stomping ground, too, and we soon became friends. She says those formative years with Smithseven — and her friendship with Vernon — still shape her perception of success, even as she struggles to identify what it means to be successful.

“I feel like I could have turned out more judgmental, more self-destructive, and more embittered if I had not been exposed to Smithseven’s overarching positive-punk ideology,” Baker says.

Among those who knew her in Memphis, there was no question that Baker would catch national attention. The question, simply, was when? The answer came after she uploaded nine harrowing songs she’d written while studying at Middle Tennessee State University. Titled Sprained Ankle, each track on the album details with vivid imagery a difficult point in Baker’s life following a relationship gone south and the distance between herself and Forrister.

The LP’s sound is rooted in her favorite artists, musicians like Pedro the Lion’s David Bazan and Death Cab for Cutie’s Ben Gibbard. Her melodies are delivered in the same shaky-but-sturdy strength that graced the Smithseven House for so many years. Then, 6131 Records signed Baker and rereleased the album, which garnered critical praise. The New York Times called it one of the best albums of 2015.

But Baker felt guilty. “One time, I started crying when NPR put a song up, because I was like, ‘Why? This should be me and Forrister, and it’s not,” Baker says.

“Shaun [Rhorer of 6131] was like, “‘No, you need to be doing as well as you can with this and seeing how far it will go, because that’s just more doors opened up for Forrister. Look at the big picture. What could you achieve if you gave in a little bit to gain a little ground?'”

As her career continues to pick up steam, publicists, managers, and agents have opened new doors. The new connections have broken down misconceptions Baker held about the music industry: “These people aren’t chewing their stogies and waving their briefcases around,” Baker says. “They don’t play an instrument, but they are equally as passionate about music.

“Everybody I meet is so non-competitive,” Baker says. “Maybe I come off as obviously green and people feel responsible for preserving that. Sharon sent me a message one time … the last line was ‘A lot of people are going to want things from you. I just want to be your friend.’ Seeing that kind of willingness to work together is absolutely inspiring.” — Josh Cannon

Andrea Morales

Andrea Morales