Those of us who are not doctors, nurses, or EMTs or others on the front lines of the fight against COVID-19 are faced with some time on our hands. The only silver lining to the situation is that our new reality of soft quarantine comes just as streaming video services are proliferating. There are many choices, but which ones are right for you? Here’s a rundown on the major streaming services and a recommendation of something good to watch on each channel.

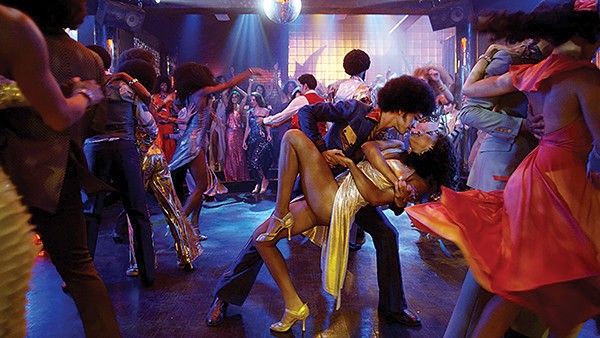

Stevie Wonder plays “Superstition” on Sesame Street.

YouTube

The granddaddy of them all. There was crude streaming video on the web before 2005, but YouTube was the first company to perfect the technology and capture the popular imagination. More than 500 hours of new video are uploaded to YouTube every minute.

Cost: Free with ads. YouTube Premium costs $11.99/month for ad-free viewing and the YouTube Music app.

What to Watch: The variety of content available on YouTube is unfathomable. Basically, if you can film it, it’s on there somewhere. If I have to recommend one video out of the billions available, it’s a 6:47 clip of Stevie Wonder playing “Superstition” on Sesame Street. In 1973, a 22-year-old Wonder took time to drop in on the PBS kids’ show. He and his band of road-hard Motown gunslingers delivered one of the most intense live music performances ever captured on film to an audience of slack-jawed kids. It’s possibly the most life-affirming thing on the internet.

From Netflix to Criterion: All You Need to Know About What’s Streaming

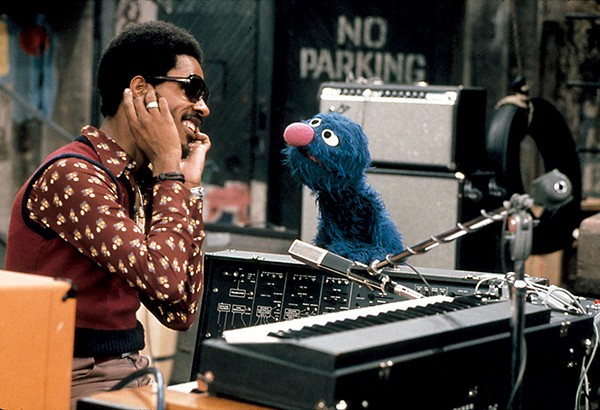

Dolemite Is My Name

Netflix

When the DVD-by-mail service started pivoting to streaming video in 2012, it set the template for the revolution that followed. Once, Netflix had almost everything, but recently they have concentrated on spending billions creating original programming that ranges from the excellent, like Roma, to the not-so excellent.

Cost: Prices range from $8.99/month for SD video on one screen, to $15.99/month, which gets you 4K video on up to four screens simultaneously.

What to Watch: Memphian Craig Brewer’s 2019 film Dolemite Is My Name is the perfect example of what Netflix is doing right. Eddie Murphy stars as Rudy Ray Moore, the chitlin’ circuit comedian who reinvented himself as the kung-fu kicking, super pimp Dolemite and became an independent film legend. From the screenplay by Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski to Wesley Snipes as a drunken director, everyone is at the top of their game.

Future Man

Hulu

Founded as a joint venture by a mixture of old-guard media businesses and dot coms to compete with Netflix, Hulu is now controlled by Disney, thanks to their 2019 purchase of Fox. It features a mix of movies and shows that don’t quite fit under the family-friendly Disney banner. The streamer’s secret weapon is Hulu with Live TV.

Cost: $5.99/month for shows with commercials, $11.99 for no commercials; Hulu with Live TV, $54.99/month.

What to Watch: Hulu doesn’t make as many originals as Netflix, but they knocked it out of the park with Future Man. Josh Futturman (Josh Hutcherson) is a nerd who works as a janitor at a biotech company by day and spends his nights mastering a video game called Biotic Wars. A pair of time travelers appear and tell him his video game skills reveal him as the chosen one who will save humanity from a coming catastrophe. The third and final season of Future Man premieres April 3rd.

Logan Lucky

Amazon Prime Video

You may already subscribe to Amazon Prime Video. The streaming service is an add-on to Amazon Prime membership and features the largest selection of legacy content on the web, plus films and shows produced by Amazon Studios.

Cost: Included with the $99/year Amazon Prime membership.

What to Watch: You can always find something in Amazon’s huge selection, but if you missed Steven Soderbergh’s redneck heist comedy Logan Lucky when it premiered in 2017, now’s the perfect time to catch up. Channing Tatum and Adam Driver star as the Logan brothers, who plot to rob the Charlotte Motor Speedway.

Inside Out

Disney+

The newcomer to the streaming wars is also the elephant in the room. Disney flexes its economic hegemony by undercutting the other streaming services in cost while delivering the most popular films of the last decade. Marvel, Pixar, and Star Wars flicks are all here, along with the enormous Disney vault dating back to 1940. So if you want to watch The Avengers, you gotta pay the mouse.

Cost: $6.99/month or $69.99/year.

What to Watch: These are difficult times to be a kid, and no film has a better grasp of children’s psychology than Pixar’s Inside Out. Riley (Kaitlyn Dias) is an 11-year-old Minnesotan whose parents’ move to San Francisco doesn’t quite go as planned.

Cleo from 5 to 7

The Criterion Channel

Since 1984, The Criterion Collection has been keeping classics, art films, and the best of experimental video in circulation through the finest home video releases in the industry. They pioneered both commentary tracks and letterboxing, which allows films to be shown in their original widescreen aspect ratio. Their streaming service features a rotating selection of Criterion films, with the best curated recommendations around. You’ll find everything from Carl Theodor Dreyer’s 1928 silent epic The Passion of Joan of Arc to Ray Harryhausen’s seminal special effects extravaganza Jason and the Argonauts.

Cost: $99.99/year or $10.99/month.

What to Watch: One of the legendary directors whose body of work makes the Criterion Channel worth it is Agnès Varda. In the Godmother of French New Wave’s 1962 film, Cleo from 5 to 7, Corinne Marchand stars as a singer whose glamorous life in swinging Paris is interrupted by an ominous visit to the doctor. As she waits the fateful two hours to get the results of a cancer test, she reflects on her existence and the perils of being a woman in a man’s world.