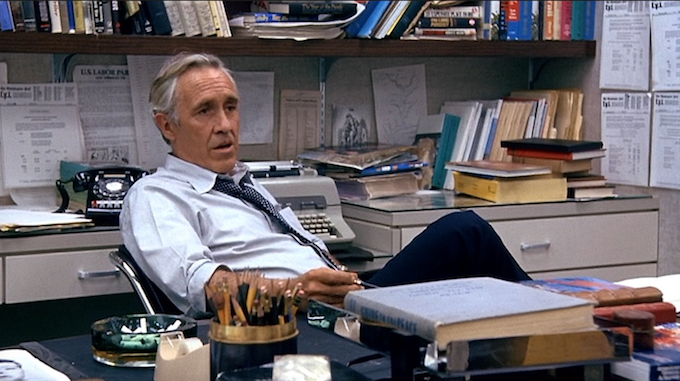

Steve Mulroy is the Shelby County District Attorney. He is also a science fiction fan who founded the annual Shelby County Star Trek Day. In this edition of “Never Seen It,” we filled in a major gap in Mulroy’s sci fi movie viewing: Fritz Lang’s 1927 silent masterpiece Metropolis.

Chris McCoy: Steve Mulroy, what do you know about Metropolis?

Steve Mulroy: I know it is an old, black-and-white, silent classic by Fritz Lang. It’s a dystopian vision of the future, I think, of a city where the workers are exploited. I think this is the one that has the robots, Rossum’s Universal Robots?

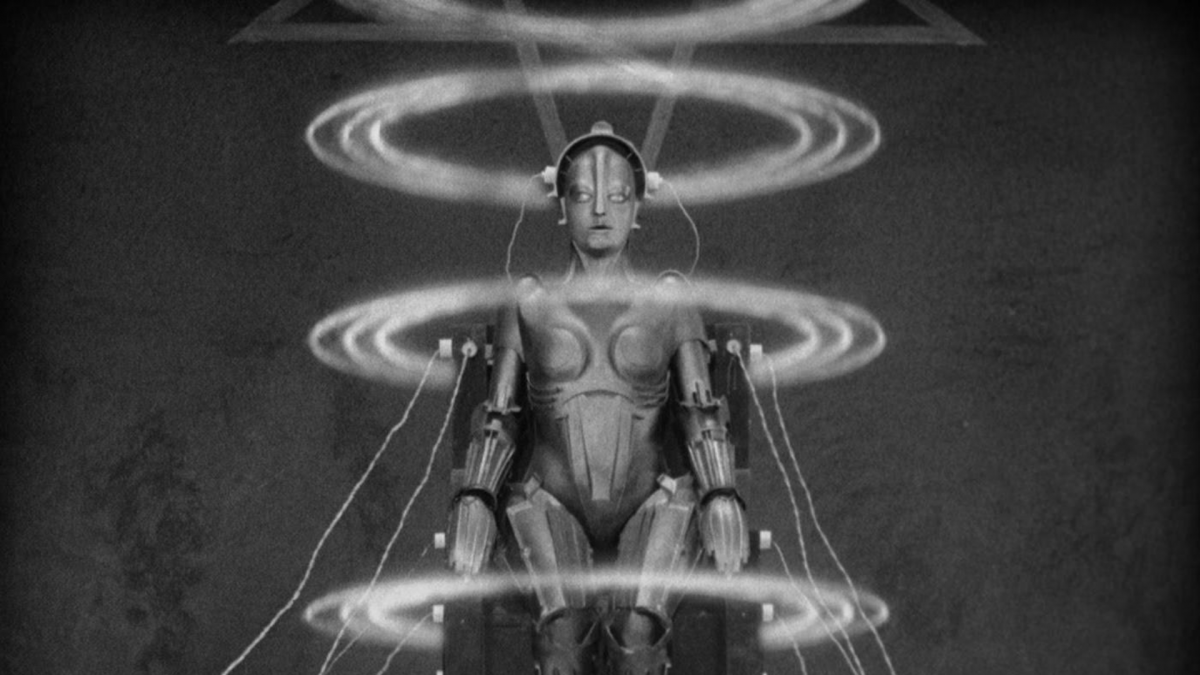

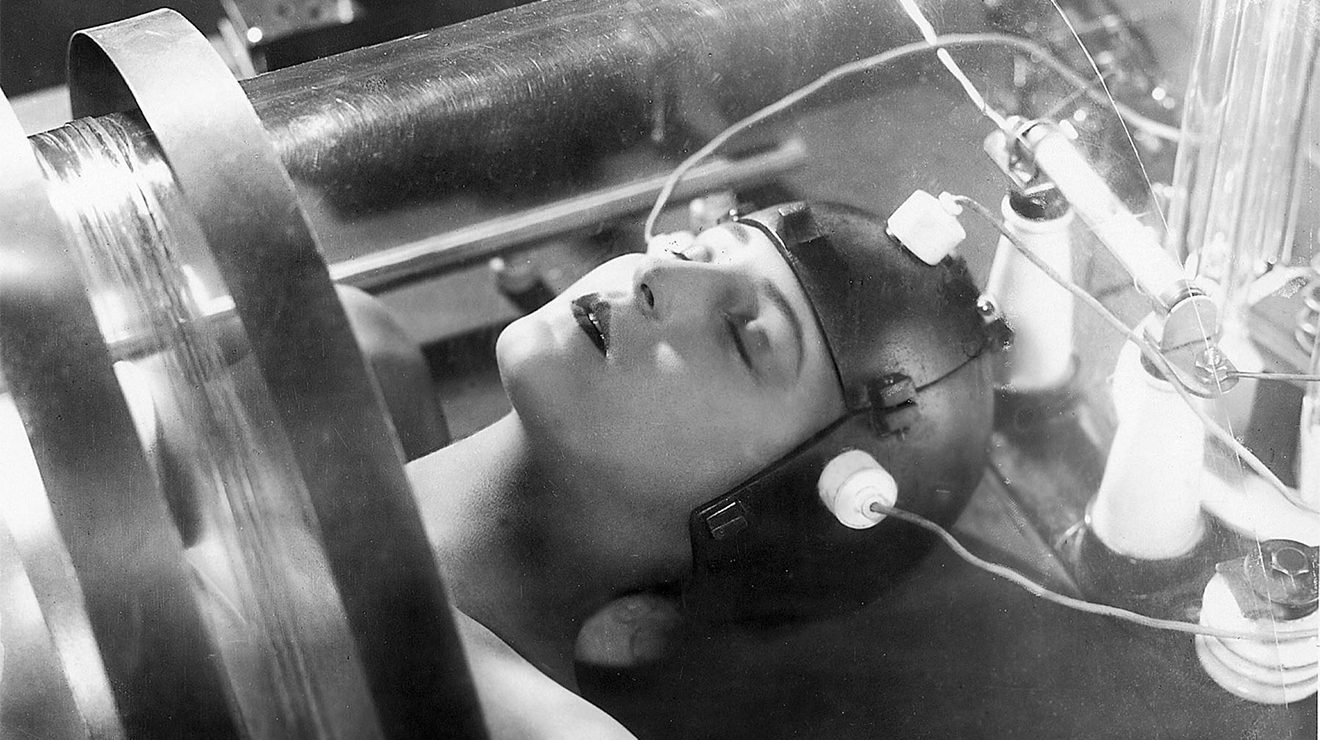

CM: This was made after Rossum’s Universal Robots, which was a stage play, but it’s one of the first films to ever actually a feature a robot.

SM: Got it.

CM: So, how this came about was, you texted me and asked, “Should I see Megalopolis or not?” And I was like, “Well, I don’t know …” And then I gave one of my typically too-complex film critic answers. Then, you were like, “Well, I wanted to see Metropolis first to prepare myself, because I’ve never seen it.” I was like, “Oh, you said the magic words!”

153 minutes later…

CM: Okay, Steve Mulroy, you are now a person who has seen Metropolis. What did you think?

SM: I liked it! It was a little on the long side.

CM: We said a couple of times, “I can see why they cut this.”

SM: Yeah, definitely could use some editing, there. But no, I mean it was great. The plot was more convoluted than I expected. It wasn’t really simplistic, so it did keep my interest. I found it visually to be really impressive — not just for its time, but on its own merits. It was interesting, all the different architectural styles. You had some Gothic, you had some Art Deco, you had some Brutalist. Both of us were pointing out how it inspired things. I thought it was reminiscent of Modern Times in overall look.

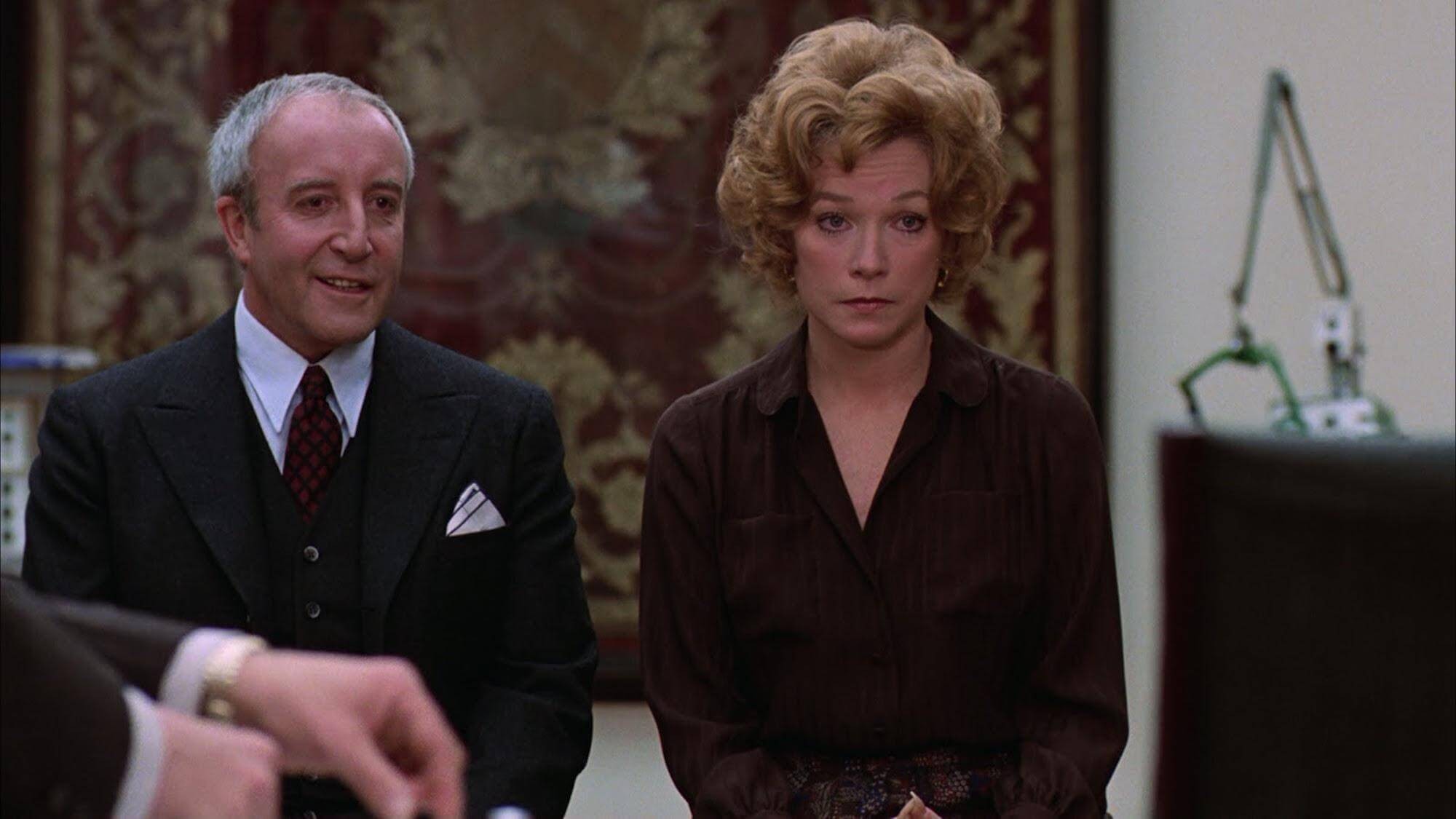

CM: You definitely see visual echoes of it all over the place. Frederson, for example, looks like Moff Tarkin from Star Wars. And then the Thin Man is clearly the Darth Vader figure. Metropolis, the city itself, looks like Coruscant — or Coruscant looks like Metropolis, rather. And of course, the robot that becomes Maria, George Lucas basically said “For C3PO, I want something that looks like that!” All of Tim Burton’s movies comes from this. It was sort of the height of German Expressionism.

SM: You said earlier that this was the most expensive movie ever made up until this point. There were those huge sets! There were so many scenes where the screen just had thousands of people.

CM: They tried to drown some children.

SM: I know, right? And there are biplanes in the city of the future that looks very much like The Jetsons.

CM: One of the things I love about looking at this now — and I’ve seen this movie a dozen times in various forms — it makes me realize that, when you’re trying to see what the future looks like, you can see it to a certain extent, but there’s stuff that you’re always going to be stuck with that’s in your reality, like biplanes. We’ve got flying cars, but they can’t have just one wing. There’s gotta be two wings! They couldn’t get past that. But there’s other parts that that they that they really nailed, like the video phone. I’m not sure television had even been conceived of, but I know there wasn’t actually a working television until a few years later. There was a lot of attention paid to information technology throughout. Fredersen, the head guy, is depicted as the one who’s at the center of this web of information. And then, when he wants to sow discord to disrupt the revolution that’s coming, he tries a deep fake, basically. Make the robot look like their leader, and tell them to do destructive things.

SM: I was going to say the plot was more complicated than I thought, because I thought it was going to be simplistic: The workers are oppressed and the elite are exploitative, and then eventually there has to be some sort of revolution, or at least some resolution. It ends up being a little bit more convoluted than that. The industrialist tries to trick them into becoming violent so they’ll have an excuse to crack down on them. And then the twist is that the real bad guy, the inventor — it’s just nihilism, right? I mean, he just wants to burn everything.

CM: He’s gonna destroy the whole city because he’s jealous of Fredersen.

SM: So on the one hand, I give it credit for being a little bit more complicated and interesting than a simplistic plot. On the other hand, I could criticize it for being a cop-out, because the workers are sheep. They’re easily manipulated in one direction or another. Only the noble people who decide to lead them, kind of like a white savior thing, have any agency.

CM: And you did point that out while it was going on. It was like, wow, the masses of the people are just changing their mind on a whim.

SM: It just takes one demagogue, and not even a full speech! Just a couple of sentences into a demagogue of a speech, and they’re ready to turn.

CM: Let’s go!

SM: So the solution is not workers asserting their rights. It’s some sort of, I don’t know, half-assed, let’s all learn to live together …

CM: It’s a centrist movie.

SM: (laughs) Yeah, yeah, yeah.

CM: But the background is, this is 1927 in Germany, right? It’s 10 years after their defeat at the end of World War I. On their eastern border is the [Russian] Communist revolution. At this point, Lenin was dead, and Stalin had cracked down, so that’s the bogeyman to them, you know?

SM: That makes sense. If the message is anti-communist but pro-worker, I guess that makes a little more sense.

CM: I think the ultimate message is, you don’t have to go too far, because if you smash the whole society, then we’re all gonna die. The flood’s gonna come and we’re all gonna die. Which is what they were seeing next door to them. But it’s also very much an admission that the workers were in a bad spot.

SM: It was definitely sympathetic to the workers. And so the theme, which they hit over your head with multiple times, is that the heart has to be the mediator between the head and the hand. What exactly does that mean? Is it some sort of like, mixed economy message? I don’t know.

CM: Are we asking for too much from this?

SM: Maybe.

CM: I’m with you. I want the text to give me answers. But is that what it’s supposed to do? Maybe it isn’t what he set out to do? I don’t know. It’s a centrist movie.

SM: Yeah, it is like, we don’t have to go that far.

CM: Freder, the son, he switches place places with a worker.

SM: It’s like The Prince and the Pauper.

CM: He doesn’t even make it through a whole shift. He’s like, “Whoa, this is too much!” He can’t cut it down there. What does her [Maria’s] solution look like when they want to save the children at the end? You take them to the rich people’s place, to the Hall of the Sons. Evacuate to the pleasure palace.

SM: I thought that was good, and it made sense. Then there was the whole Whore of Babylon thing, which was an interesting side note. It definitely trafficked in the Madonna/whore binary, which was probably a product of its time.But notice the evil effect that the robot Whore of Babylon has in the upper classes. It makes them more decadent and dissolute. In the lower classes, it makes them violent. I just found it sort of an interesting dichotomy.

CM: There’s also this whole biblical thing. There’s a digression into the recreation of the story of the Tower of Babel …

SM: Slightly changed.

CM: Yeah, because it becomes like a …

SM: … a class warfare thing.

CM: Which is not what that story is about!

SM: I have to say I am actually pretty impressed with how sophisticated at all is, visually and thematically. When I heard it was 1927, I was expecting something really primitive.

CM: Some of those composite shots are incredible! I counted one, it had ten elements! The miniature work is incredible. too.

SM: Every shot where they were using miniatures or whatever to show the city from different angles was elegant and beautiful, and kind of striking. It compares favorably to some stuff from many, many decades later.

CM: There’s a reason people have been ripping this movie off for a hundred years.

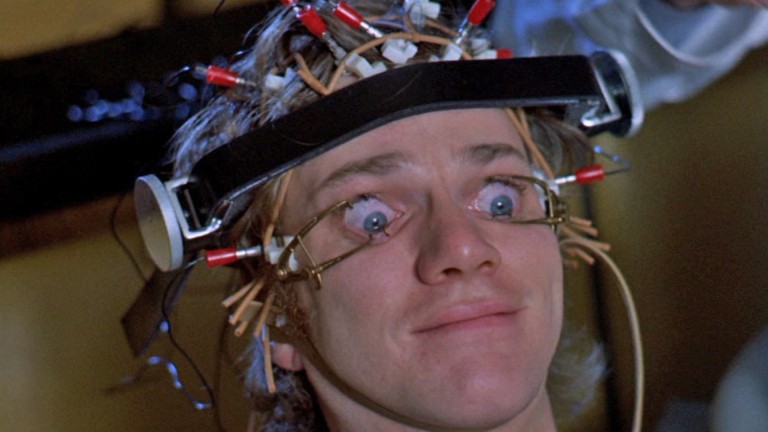

CM: The actress who played Maria, Brigitte Helm, she’s incredible. I love watching actors do this in a movie, where they’re playing two different versions of the same person, and you can tell which one is which by the way they hold their shoulders.

SM: She does it very good job of portraying the dichotomy between the two versions of Maria. I’m forgiving the overdramatic, of its time, big acting because you don’t have the addition of the sound. You don’t have the words, right? So you’ve got to just use facial expressions and gestures to convey everything. I get all that. What bothers me about it, though, is everything takes too long. A reaction that should be a couple of seconds is 10 seconds. I don’t know if it was just the style of the time or whether it was a technical thing that they couldn’t cut as nimbly.

CM: I think part of that is stylistic and part of it is the people who are watching this originally did not have the visual vocabulary that’s been built up over the last hundred years that you and I do. There’s a trope that you see a lot in American films from the ’30s and ’40s, where, if they want to change locations, there’ll be an exterior shot, and you see the car drive up. We wouldn’t bother to do that.

SM: I give it a lot of credit. It’s more intelligent than a lot of movies that are made nowadays.

CM: God, yes!

SM: I’m not a purist. On the one hand, I do want to respect the director’s vision, so I can understand why people don’t want to colorize movies, or whatever. But I almost wish that there was floating around a more tightly edited version of this, just so that it would have a better chance of getting wider distribution among the general public.

CM: Well, there were! There’ve been a bunch of cuts of it over the years. We were watching the fully restored version. But that’s why some of it was lost for a long time, because it was cut way down for the American market. This version was pieced together out of several surviving negatives, one of which was found in Argentina.

SM: The slimmed down version that was shown to the American market, did it have that missing sequence where the father and the inventor fight it out?

CM: No.

SM: So that was never shown?

CM: No, that was never shown. That’s why it’s lost.

SM: In those versions, did they have a title card that explained it?

CM: No, they just cut it out.

SM: That seems like a pretty essential scene to just not show.

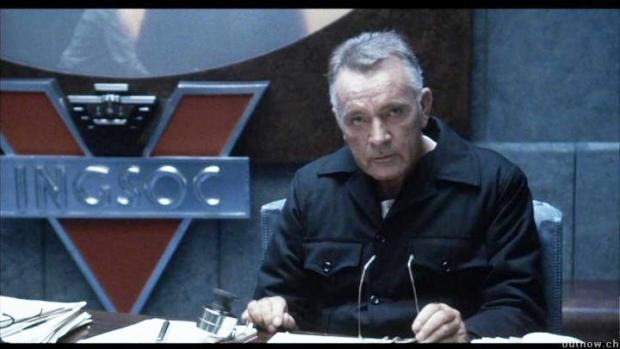

CM: Exactly. I think that was part of the reason why people didn’t understand it. You have a balance: this version is the completest version, and it is draggy in places, but you get the full sweep of the story. What was shown in America for a long time was butchered so badly that the plot hardly made any sense at all. There was a version that was released in the ’80s that was restored by Georgio Moroder, and it was colorized, but it was a really early colorization experiment. That’s the version that most people our age had seen. I think it’s like 90 minutes long, has songs by Freddy Mercury. It’s more like a giant music video. That’s when I was first introduced to it. I think probably on Night Flight, late night music video TV. A lot of people like to rescore it, too. One my favorite movie theater experiences of all time was an Indie Memphis screening where the Alloy Orchestra did a live score in front of an absolute packed house at The Paradiso, and it was amazing.

SM: I was just trying to think of all of the iconic sequences that this seems to have inspired.

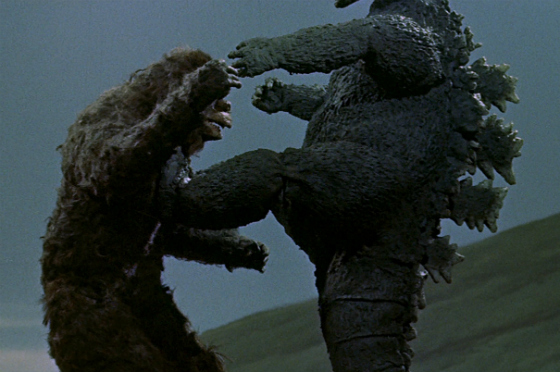

CM: King Kong carrying Faye Wray up to the top of the building.

SM: I think the machinery sort of inspired Modern Times.

CM: Definitely Modern Times. Then Vertigo, the whole bit in the cathedral at the end. Hitchcock lifted the visuals on that, straight up. There’s so much more. People will use little riffs from it, too, because it’s taught in film schools.

SM: Frankenstein, with the inventor’s labs.

CM: Yeah, Freder hallucinates at the drop of a hat. Like, you need to chill, you know? I think it inspired Foundation, the city-planet of Trantor.

SM: Even those party scenes look like Baz Luhrmann’s Great Gatsby.

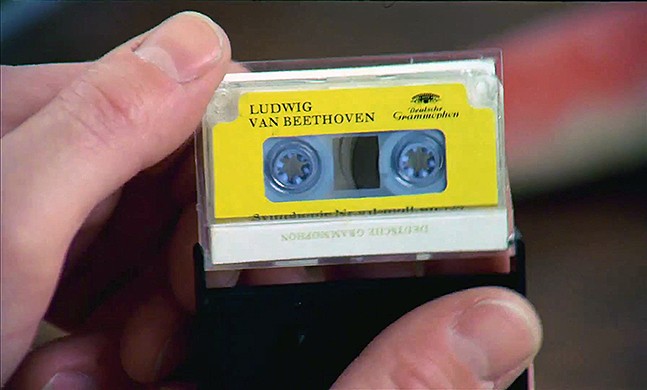

CM: I also noticed this time the machine man. That’s a whole Kraftwerk album.

SM: I thought it was odd that they called it the machine man since it was so obviously a woman.

CM: Rotwang is just a a great villain. He’s got the mechanical hand, like Dr. Strangelove, which you pointed out.

SM: He’s got the wild hair. He’s got scientist hair.

CM: The boss Joh Fredersen, is like capital, right? The workers are like labor, right? And then there is the church, which is Maria, and then there’s an actual church, too, the cathedral. Rotwang is science. But Rotwang is the ultimate villain in the piece. It’s science fiction, but then there’s this anti-intellectual element to it, too.

SM: Right. But it’s also anti-Luddite.

CM: It is anti-Luddite, because it’s like, we have to have this progress. When they smash the machines, everybody dies. These are still debates that we’re having today, because we’ve never really gotten a good answer to them. Like you pointed out, the film doesn’t come to a satisfactory conclusion, either. They managed to lay out the problem, but they did not come to a satisfactory conclusion.

SM: Like you said, it’s probably unfair to expect a five-point plan at the end of it, but there was a through-line there. It was sympathy for the plight of the workers, but anti-Luddite, and anti-extremism.

CM And anti-violence. Violence is not gonna solve these problems. What’s your bottom line? Would you recommend people out there in TV land watch Metropolis today?

SM: If you are a cinephile you definitely need to see it, or if you’re really interested in history. I would recommend it for the average viewer, but I’d have to warn them that it’s a little patience taxing. I think maybe for the average viewer, I might recommend the slimmed down version.