Derek Haire, a young political activist and sometime blogger, had by late June seen his long-standing devotion to Steve Cohen rewarded with a paid position in the 9th District congressman’s reelection campaign. As Haire knew, the grunt work in most campaigns is done free, by volunteers whose devotion serves as both motivation and reward. So he was blissful at the opportunity to be a bona fide staffer, though he was cautioned that his hours would be long and his pay would be minimal. “Steve Cohen isn’t Santa Claus” was the stock phrase, though the congressman’s pay scale was level with the norm, maybe higher.

Haire was put in charge of a detail canvassing neighborhoods in the district and asking residents for permission to place Cohen campaign signs in their yards. One afternoon, he drove a borrowed truck up a bleak Orange Mound street, dutifully checking for ideal locations. He had just parked when he noticed a cluster of male teens, all sporting cornrows and gangsta threads, approaching his vehicle from both sides. Even as Haire was calculating what to do, they were upon him, looking into his side windows, at the anti-youth-violence slogans painted on the truck, and finally at the blue-and-gold campaign signs in the bed of the pickup. Haire made bold to lower the window on the driver’s side.

“What are you doing here?” asked one of the youths, his face an impassive mask.

Deliberating only a second — during which his main thought was that there he was, a slightly built white kid by himself in unfamiliar terrain, surrounded by some dour-looking dudes — Haire said, “I’m giving away Cohen campaign signs. You want one?”

The youth who had spoken leaned into Haire’s car and craned his head around, peering again at the stacks of signs in the back.

“Yeah!” he said finally, with the beginnings of a smile. From behind him came another voice: “Yeah, I want one, too.” And another: “Hey, could I have one?”

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

Before it was over, Haire and the youths had formed a posse of sorts, working the block up and down, pushing the wire ends of the campaign signs into yard after yard, turning at least that modest section of Orange Mound into what appeared to be an outpost of apparent enthusiasm for the incumbent.

Haire’s experience was counterpointed at the week’s end, when a Cohen supporter hosted a meet-and greet for the candidate in Uptown Square, a newish downtown development redeemed from what had been the Hurt Village housing project. Uptown Square is an experiment in mixed-residency living, a far cry from the ghetto that Hurt Village had become before it was razed away into history.

Consistent with the venue, the people on hand were something of a diverse mix. During the question-and-answer session that followed Cohen’s brief remarks, one man, a young Republican, asked about a celebrated incident at the opening of the 2006 state legislative session, destined to be Cohen’s last, when the then state senator, with the full knowledge that he would likely be a candidate for Congress that year, made a point of challenging on church-vs.-state grounds the overtly Christian sentiments of a Baptist pastor’s invocation.

Impolitic as that seemed to virtually everybody at the time, it was yet another instance of Cohen being Cohen, of a public figure who, for better or for worse, tends to let whatever is bubbling (or seething) in his subconscious find its way to the surface.

(A more recent example was his quip, delivered both to a local reporter and to assembled Democrats at this year’s annual Kennedy Day Dinner, comparing Hillary Clinton, then still vying for the presidency, with the fanatically determined character played by Glenn Close in Fatal Attraction; the remark drew national attention and may have been a factor in the decision by Emily’s List, the feminist pro-choice PAC, to endorse opponent Nikki Tinker.)

Cohen’s reply to the questioner at Uptown Square, however, was measured. Yes, he said, he remained a firm defender of the principle of separating church and state. But he had come to realize, during his year and a half of congressional service, that his African-American constituents had a different conception of the relationship between church and state, one that he respected.

That difference would be in play two days later, when Cohen, like any realistic candidate running for office in inner-city Memphis, made an obligatory round of Sunday church stops.

One of those was at New Olivet Baptist Church, whose minister is the irrepressible Kenneth Whalum Jr., a maverick school board member and, some say, aspirant mayor. Whalum’s religious style is equal parts Old Gospel and New Wave and involves extended spells of congregational dancing and singing, led by the energetic pastor himself.

by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks

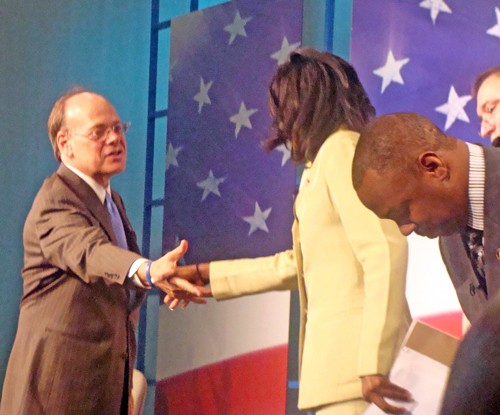

Left to right: Joe Towns, Nikki Tinker, and Steve Cohen

“Come on, Congressman Cohen!” Whalum exhorted from the pulpit, as he spotted Cohen, accompanied by his local office director and all-purpose factotum Randy Wade, threading down the center aisle amid the gyrating and syncopation of Olivet’s worshippers. The congressman, famously hip in private, was no doubt restrained from too much direct participation both by the protocol of his office and by the fact of a bad leg damaged by childhood polio.

But he was front and center soon enough, when Whalum called a pause and asked Cohen to rise. He did, to cheers from the congregation, and was beckoned into the center aisle again by a congregant who made a point of bestowing on him a prolonged and ostentatious hug. More cheers. “You can’t get away from her,” Whalum observed in delighted amusement and finally said, in a mock-protective tone, “Ushers, sit this boy down. Sit this boy down!”

The fun over, Whalum shifted into serious mode and thanked Cohen for “being so gracious when our young people visited Washington” and for other favors. Another extended song break later, Whalum announced that the congressman needed to leave in order to visit other churches and upped his volume a bit to proclaim, “We love Steve!” Again, the cheers, as Cohen made his exit via a side door.

Outside the church, on his way to the next venue, Cohen was properly appreciative, even somewhat awed. “This is the best I’ve ever been received,” he said. “This is home for me.”

The reality, of course, is that the first-term incumbent has serious competition for the affection of Memphis’ black churchgoers, an important segment of a district whose voting constituency is 60 percent black. It comes from Nikki Tinker, an African-American lawyer with a killer smile and a resume that includes both up-from-nothing beginnings in home state Alabama and a prestigious job as a local attorney for Pinnacle Airlines.

It also includes past service as a campaign manager for former congressman Harold Ford Jr., though both the duration of her time on the job (on the stump she claims it lasted five years) and the demands of it (Ford was never seriously contested during her tenure) have been privately disputed by other Ford staffers. It is also unclear to what extent remnants of the once-mighty Ford organization are supporting Tinker, if at all — though Shelby County commissioner Sidney Chism, another political broker of note, is definitely with her, as are such name politicians as state House of Representatives pro tem Lois DeBerry, city clerk Thomas Long, state representative Ulysses Jones, and former county commissioner Walter Bailey.

That, however, comes close to completing the list of influential Tinker supporters. What is also interesting is who is not supporting Tinker — including virtually all of the African-American candidates who, along with Tinker and Cohen, composed the 15-member congressional field in 2006, when Harold Ford Jr. vacated the 9th District seat to run for the U.S. Senate. That would include those for whom race was never an issue and at least two — former county commissioner Julian Bolton and consultant Ron Redwing — who two years ago proclaimed that the district should be represented by a black but who publicly support Cohen this time around.

Tinker’s decision to run again this year is probably influenced more by simple mathematics than anything else. Having finished only a few thousand votes back of Cohen in a field of 15, most of whom (including Cohen himself) competed with her for the district’s black vote, why should she not, two years later, try to go one-on-one?

She has been designated as a “consensus” black candidate this time around by several holdouts for the idea that a black, and only a black, should represent the 9th District in Congress. Perhaps foremost among those is the Rev. LaSimba Gray, who led a failed effort to settle on such a candidate two years ago but whose choice this time around was almost a matter of default.

Besides two candidates considered fringe, only state representative Joe Towns, an African-American candidate who has, however, disavowed the race label and who, in any case, filed to run after Tinker’s selection, was available.

Gray was instrumental in arousing opposition to Cohen among members of the Memphis Baptist Ministerial Association — ostensibly in opposition to the congressman’s vote in 2007 for federal hate crimes legislation (which Gray and others branded as gay-friendly). But a few outspoken members of the association made it clear that Cohen’s real offense was his race or his religion. A black pastor in Middle Tennessee launched a supportive attack against Cohen under the slogan “Steve Cohen and the Jews Hate Jesus.”

In any case, Tinker, like Cohen, was a visible presence in predominantly black churches this past Sunday, and she had with her such luminaries as DeBerry, Long, and — pièce de resistance — Congresswoman Stephanie Tubbs-Jones of Cleveland, Ohio, an ebullient politician who supported Hillary Clinton’s presidential bid to the end and who has so far been the only member of the Congressional Black Caucus to step forward on Tinker’s behalf.

Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks

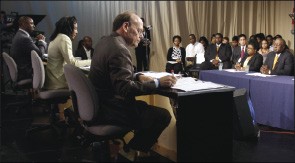

Steve Cohen works the crowd at the WREG debate.

After being introduced by DeBerry in the pulpit of Monumental Baptist Church on Sunday, Tubbs-Jones delivered an enthusiastic endorsement of Tinker as “a young woman who is talented, who is skilled, and who deserves to represent the city of Memphis in Congress.” After scolding the media for allegedly making too much of Tinker’s being a black woman, Tubbs-Jones repeated, “Nikki Tinker is talented and qualified, and, praise God, she’s a gorgeous black woman.”

Appearing in the pulpit on her own behalf, with two small children in tow, Tinker said, “This is not about my race, it’s not about my religion. I’m concerned about where these young people are going to be 20 years from now.” Reprising the elements of a TV commercial she ran in 2006 and which has been recycled this week, she said, “You all know my story. You know I was raised by a strong-working, hard-working single mama and a disabled grandmother, who lost her eyesight to diabetes. And when I’m traveling through Memphis, up and down South Parkway and Whitehaven and Boxtown and Westwood and New Chicago, I see people like my grandmother, who are afraid to get to the mailbox, still looking for help and support … .”

Tinker continued, “I will go through the fire if I have to. … And I want to tell you, I will deal with this media. I say I will fight ’em and do everything I have to do. I’m looking for some prayer warriors, though.”

And, as she and her party were departing the sanctuary on their way to other churches, Monumental’s pastor, the celebrated Rev. Billy Kyles, reminded his congregation of his involvement in prior 9th District races, beginning in 1974, when Harold Ford Sr. became the first elected black congressman in Tennessee, and continuing through the decade of Harold Ford Jr.’s tenure in office.

“We’ve been trying to get that seat back,” Kyles said. “It is our seat.”

Whatever the stand of individual pastors, though, there was clearly no consensus in the black community concerning the congressional race. In the minutes before Tinker’s arrival at Monumental, there had been some interesting byplay in the lobby between two church greeters — Rodney Whitmore, a deacon, and Johnny Raney, an usher.

“That Steve Cohen has done a pretty good job in Congress,” Whitmore said. “I think I’m going to vote for him.”

“He might have done a good job,” Raney responded. “But I’m not going to vote for him.”

It went on from there and concluded with the two church officials engaging in some mock shadow-boxing, but the brief dialogue capsulized the conflict of priorities that was one of the central dramas of the 2008 congressional race, as well as the single greatest unknown quantity.

Every old saw has an ideal application, and Sunday night’s televised debate involving three 9th District congressional candidates perfectly invoked that sardonic chestnut which goes, “All have won, and all must have prizes.”

When the sometimes stormy hour-long affair at the studios of WREG-TV had run its course, backers of incumbent first-term Democrat Cohen ended up being reassured of his unmatchable experience and prowess. Those supporting Cohen’s chief primary challenger, Tinker, were likewise convinced of their candidate’s common touch and oneness with the people. And Towns’ claque (such as there was before Sunday night) were pleased with their man’s singular common sense and panache, as well as his full-out assault on unidentified “special interests.”

Conversely, detractors of Cohen might have seen him as somewhat smug and supercilious; Tinker’s opponents might feel justified in seeing her as shallow and opportunistic; and those prepared to discount Towns could have likened him — as did Richard Thompson of the Mediaverse blog — to another notorious spare political wheel, John Willingham.

The actual impact on whatever portion of the electorate watching the debate was probably a composite of all these points of view. And, while Cohen might have ended up ahead in forensic terms, the equalizing effect of the joint appearance and the free-media aspect of the forum had to be a boost for both his rivals.

Questioning the contenders were Norm Brewer, Otis Sanford, and Linda Moore — Brewer a regular commentator for the station and the latter two the managing editor and a staff writer, respectively, for The Commercial Appeal, a debate co-sponsor, along with the Urban League, the activist group Mpact Memphis, and WREG.

All three panelists posed reasonable and relevant questions, as did the two audience members who were permitted to interrogate the candidates, though the issues raised (or the answers given) tended to be of the general, all-along-the-waterfront variety. All three candidates viewed rising gas prices and the home-mortgage crisis with alarm, and all wanted to see improved economic horizons. Each claimed to have a better slant on these matters than the other two, but Cohen could — and did — note early on that neither Tinker nor Towns had found fault with his congressional record to date. “I appreciate the endorsement of Miss Tinker and Representative Towns for my votes,” he said laconically.

The first real friction was generated by a question from Moore, who touched upon what she called “the elephant in the room” — namely, the importance of racial and religious factors in the race.

This brought an unexpected protestation from Tinker that she was “not anti-Semitic” and regarded it as “an insult to me” that she had been so accused. That such an allegation had been made was news to most of those attending, though one of her chief backers, Sidney Chism, had made the point last week, addressing the Baptist Ministerial Association on her behalf, that Jews were likely to vote for co-religionist Cohen.

And well they might, on the general principle that voters tend to gravitate toward candidates of like backgrounds. There has been no suggestion from the Jewish community, however, that a Jew should represent the 9th District, while Tinker and many of her supporters openly assert that the majority-black urban district should be represented by a black congressman. As Tinker put it Sunday night, noting the demographic facts of life in Tennessee’s nine congressional districts, “This is the only one where African Americans can stand up and run,” she said. “Can we just have one?”

If Tinker expected agreement from Towns, she didn’t get it. “If you’re black and no good, you’re no good. If you’re white and no good, you’re no good,” he said, in pithy dismissal of the issue. That did not stay him, later on, from chastising Cohen for the then state senator’s anguished reaction to a lower-than-hoped-for black vote in 1996, after losing his first congressional race to Harold Ford Jr. that year.

Cohen’s response was that his frustration had mainly stemmed from the vote garnered against him that year by the late Tommie Edwards, a relatively uncredentialed opponent in Cohen’s simultaneous reelection race for the state senate. The congressman noted that he went on to win the black vote in the 2006 general election. As for 2008, Cohen, a sometime speaking surrogate for presidential candidate Barack Obama, cited voter acceptance of racial differences in his own case, that of Obama, and that of Shelby County mayor A C Wharton, an African American.

“We’ve turned a corner,” Cohen maintained. “Barack Obama, A C Wharton, and Steve Cohen are in the same boat, and it’s a boat that’s moving forward.”

Towns made an effort to rock Tinker’s boat as well, castigating as “demeaning” her frequent declarations in a TV commercial that she’s running in part to make sure that her infirm grandmother’s government check continues to get to her porch.

Tinker’s pitch Sunday night was heavy in such personally tinged declarations, which constituted a counterpoint of sorts to Cohen’s frequent citation of his endorsements (the NAACP, the AFL-CIO, the Sierra Club, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, and Judiciary chairman John Conyers, among others) and the financial benefits to the district and other accomplishments from his legislative record, both in Congress and previously, during his several decades as state senator. In a sideswipe clearly directed at the incumbent’s ubiquitous presence in the district, she said, “People are tired and fed up. At the same time we’ve got elected officials just running around here and going to galas and, you know, giving out proclamations and renaming buildings.”

Debate moderators Richard Ransom and Claudia Barr had their hands full keeping accurate tabs on time allotted to the principals, especially during a segment allowing candidates to accuse and challenge each other. Tinker availed herself of such a moment to ask Cohen, who holds an investment portfolio, if it was true that he “profited” from an increase in gasoline prices.

The congressman rebutted the notion, contending, “I always vote against my own personal financial interests.” He then turned the question around on Tinker, inquiring about the stock holdings in her pension or 401(k) accounts at Pinnacle Airlines. Cohen also pressed Tinker on her self-definition as a “civil rights attorney,” extracting her grudging concession that she had served Pinnacle for the last decade on the management side of labor-relations issues.

But Cohen’s relentless prosecution of that line of questioning also yielded Tinker what may have been an effective moment in self-defense.

When the congressman interrupted Tinker at one point, insisting on a direct answer to a question, she responded, “Mr. Cohen, I’ve respected you, and I’ve allowed you to [finish your answers]. … I’m asking for your respect, as humbly as I know how.” Apropos his allegations about the nature of her employment, she contended that her airline’s flight attendants and baggage handlers are “on the front lines with me and supporting me in this campaign.” She concluded, “My heart is pure, and I’m satisfied with what I’ve done.”

It remains to be seen to what degree viewers were satisfied with what the candidates, together or singly, had done in a debate that, as Towns suggested, was meant to “allow … us to see who is who and what is not.”

One issue that remained unexamined was that of abortion, on which Cohen has long been known as pro-choice, while Towns has just as resolutely proclaimed his pro-life views. Tinker’s position has been shrouded in mystery, though, as indicated, she received an endorsement — and presumably the promise of funding — from pro-choice group Emily’s List.

CA columnist Wendi Thomas, originally scheduled to be a panelist for the debate, wrote a column speculating on Tinker’s abortion-issue dilemma, since many of her supporters are virulently anti-abortion. One result of that was apparently a negative reaction from the Tinker camp, who saw Thomas’ column as over-critical and, according to debate organizers, requested that Thomas be replaced as a panelist.

One result: Moore was there in Thomas’ stead. Another result, inadvertently or not: No question about abortion was ever asked.

Less than a month remains before the 9th District’s Democratic voters resolve the issue on August 7th. Early voting begins Friday and continues through Saturday, August 2nd. Cohen held a substantial fund-raising lead over Tinker through the first quarter of 2008, with second-quarter totals due to be known within the week. (See Politics, p. 13, for more information on early-voting locations and financial disclosures.)

As of now, no further public debates are scheduled — a fact unhelpful to Towns, who has raised virtually no money and who probably needs more free media like Sunday night’s to gain real traction. Meanwhile, warriors Cohen and Tinker had ample money to spend and were running their first round of TV commercials virtually nonstop — Cohen touting the record of his first term in Congress and Tinker making her porch-top plea.

Further pyrotechnics may be in store before the summer’s fireworks season is done, and the Flyer will bring you news of them. A last comprehensive look at the 9th District race will be included in our pre-election issue of July 31st.

jb

jb  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks  by Justin Fox Burks

by Justin Fox Burks  Justin Fox Burks

Justin Fox Burks