“To study history means submitting to chaos and nevertheless retaining faith in order and meaning.”

— Hermann Hesse

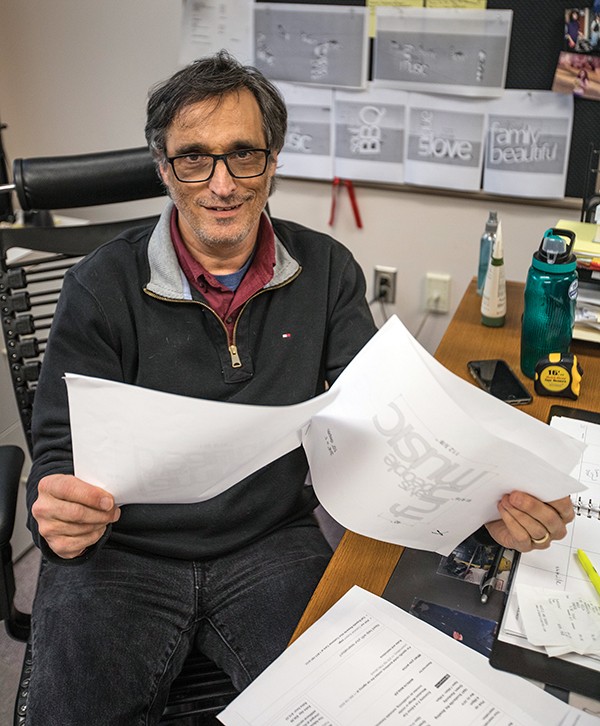

Steve Masler, anthropologist and manager of exhibits at the Pink Palace Museum, would no doubt agree with this quote. In fact, he told me as much when I spoke to him about the museum’s grand exhibit, “Making Memphis: 200 Years of Community,” running from March 2nd to October 20th. “My feeling is that the exhibit’s design is an integral part of how you interpret it. It’s organized chaos, which is purposeful, because that is really the way that history works.”

Indeed, visitors to the exhibit should prepare themselves for total immersion in the images, artifacts, and sounds of the city. And its words. Let it be known that the Pink Palace has the biggest words — some up to six feet high. The exhibit team’s exhaustive community outreach program through 2018 elicited the words people most associate with the city, translated those into word clouds, and then made the word clouds larger than life with 3D sculptures of the most popular ones.

Photographs by Justin Fox Burks

Photographs by Justin Fox Burks

“So when you walk in through these words, you see what current-day people have said Memphis means to them,” Masler explains. “Then you go into the room, which is full of things. Five thematic areas, or pods, and 10 chronological monoliths. And they’re all tied together with colored threads. Each of the five theme-pods has a color, sending out four threads to the other pods, and with threads of different colors coming in from the others. So overhead will be this web, and that’s what the story really is: This intertwined, complicated web of things. If you follow them, they go to certain specific points in the other pods.”

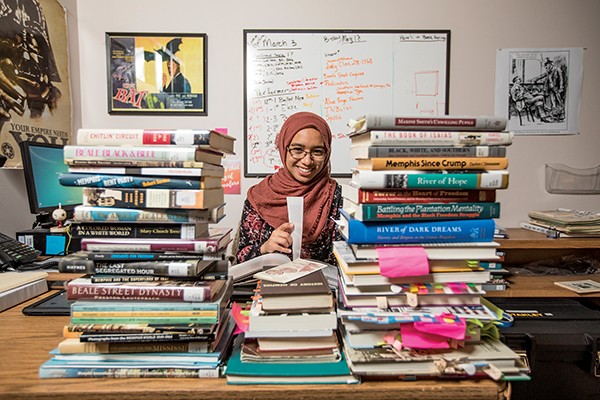

Caroline Carrico, supervisor of exhibits, chimes in: “The idea being, what makes Memphis today is the intersections of all these different stories, these different lines of thought. Our themes are Art and Entertainment, Commerce and Entrepreneurialism, Heritage and Identity, Migration and Settlement, and Geography and the Environment. So things come up in different places. For example, when we were putting it together, we’d ask things like, ‘Where are we going to put Robert Church?'” But Church, considered the South’s first African-American millionaire, had his hand in so many facets of the city’s early growth that choosing where to address his legacy was simple, according to coordinating curator Nur Abdalla: “Everywhere.” Carrico explains further, “So there’s not just one place where you read about Robert Church. You go through the whole exhibit, and find him lots of places.”

Steve Masler, manager of exhibits at the Pink Palace.

This approach, emphasizing the disparate, yet interconnected aspects of the city’s society and environment over time, is not a typical historical presentation. In the beginning, the team looked back at similar retrospectives in the past. “We have a pamphlet from the centennial, in 1919, that talks a lot about [city founders] John Overton, James Winchester, and Andrew Jackson … and Davy Crockett, who was barely here,” Abdalla says.

Carrico adds, “In the mansion, we actually have the sesquicentennial mural, and it’s very startling when you look at it. It was 1969, the year after MLK’s assassination, and the only African American on there is W.C. Handy, and he’s standing in a cotton field. The Civil War generals take up much more area than that. So we very starkly did not want to do that. We had a really clear picture of what we didn’t want the exhibit to be when we started, but not a predetermined plan of what it would be.”

Caroline Carrico, Pink Palace’s supervisor of exhibits, inspects the artifacts.

Abdalla (recently honored in the Flyer‘s “20<30” cover story) dove deep into hundreds of sources on Memphis history, distilling their insights for the team, who then collectively developed the focal points of the exhibit. “When you read the stuff that was written in the 1930s, and even the sesquicentennial in ’69, you read a lot about Jackson, Overton, Winchester, and of course they’re important. But they don’t come up in all our pods. They come up at the beginning. … We also find that every single pod has to talk about race. Because everything that happened here, just because of the social order, has to do with race.

“Even in the Geography and the Environment pod, race is discussed,” Abdalla elaborates. “We talk about pollution, neighborhoods prone to flooding, the planning of the interstates, which were built through the poorest neighborhoods to split them apart purposely.”

Nur Abdalla, coordinating curator for “Making Memphis: 200 Years of Community.”

As I spoke with the team, their acute sense of responsibility in curating the city’s history was palpable. As Masler recalls, “Ours is one of the biggest events, if not the biggest event, that’s going on for the [city of Memphis] bicentennial. And we didn’t know that that would be the case. But then we looked into what the city was doing, and it turned out that there wasn’t much, that we know about at least. It’s more spread out. In a way, they see it more as a tourism booster and a community feel-good event.”

Abdalla points out that the Pink Palace’s ambitions aimed higher — and wider. “We are the museum of the history of Memphis and the Mid-South, so there’s no way we were going to tell the stories in ways they’ve already been told. We started out with these huge research documents, these large essays that tie into these themes. And then you have to cut that down in ways that retain those meanings. So the pods and timelines are stepping stones. We’re telling the stories that have always been told, but in different ways, as well as stories that haven’t been touched on in other tellings of Memphis’ story.”

This includes looking at the grimmer aspects of Memphis’ past with eyes wide open. How, I asked, would they confront the city’s history of slave trading?

“We talk about it in various places when it comes up,” says Carrico. “But we confront it in depth in our Commerce and Entrepreneurialism pod, where we talk about slaves as merchandise, which was Nur’s suggestion.” Abdalla adds, “And we have a child’s shackles, relating to the text on the pod. So that’s where the artifacts really enrich the meaning.”

Such facts, presented point-blank, speak for themselves, as Masler clarifies. “The slaves were a good that were bought and sold in Memphis. And we were able to talk about the slave dealers in that way. What we say is pretty straightforward. We don’t say ‘and this was slavery, and slavery was bad!’ We say, ‘People were sold and were considered like merchandise.’ And our hope is that people look at that and go ‘Oh, that’s horrible.'”

In some cases, past issues of oppression that live on today are better taken up in the chronological sections, rather than in thematic pods. “We were trying to figure out how to talk about the Confederate statues,” says Carrico, “something that is clearly an issue now, and has a long past. It turned out that it was best to tell it on the timeline. So you can show when the Civil War happened, then talk about the later Lost Cause mythology and the Nathaniel Bedford Forrest statue. Then, after King’s assassination, we talk about the Jefferson Davis statue. And in the very last section of the timeline, we talk about #takeemdown901. Because the last timeline goes up to the present day.”

As it turned out, representing our current history and its demographic shifts required some creative thinking. “We have an amazing collection here, but recent communities were more of a challenge. We didn’t want to just make it black and white. We’ve had a Chinese community here since the mid-19th century, and the Chinese Historical Society was great, because they’re a historical organization. But when we tried to collect from the Latino community, it was harder than we were expecting. Then, through a personal connection with a mom’s group, of all things, we were able to get a tortilla press and some indigenous instruments. Or, we realized we weren’t representing punk and women in music. So we found a Klitz artifact through Steve’s friend Marcia Clifton Faulhaber. It’s not always the organizations that you think are the best sources for a community. You have to work your relationships in different ways.”

Abdalla notes a positive side to these unorthodox methods: “Yes, the artifacts are a bit of a challenge, but also an opportunity, because now we’re developing connections with these new groups of people to build up our permanent collection in the future. This is what happens when you go out asking people for things.”

Though the team’s exhibit planning appears to have unfolded in classic Memphis style, relying on friends and friends of friends, it also embodies some cutting-edge thinking in museum design. As Masler explains, “In the museum world, there’s a lot of thought going into what community involvement really means. With our exhibit — and we have never designed and built from scratch, in house, an exhibit this complicated — the word cloud you enter through is totally done by what people said.”

To that end, nearly 30 pop-up events were held last year, either at the museum itself or in different communities, where people could note what Memphis meant to them, and, if they wished, be photographed and even recorded on audio. “Part of the whole thing was community input and inclusiveness,” Masler goes on. “So we did these different word clouds at different times of the year, different locations, different aged people. Different neighborhoods. Each one has its own character. Caroline’s idea was to lay them out on a map, so you could see that at this particular date, this particular place, these people said these were their words. Across the city as a whole, the most common word people said was ‘Home.'”

“And then,” Carrico adds, “we took these events that Nur was taking out into the community, and designed them into the exhibit in a seamless way. It was part of the design from the beginning. We didn’t want to ask their opinion and then just slap it on at the end.” Thus, a mural of those who agreed to be photographed will cover one wall, and a “community curated” display case will feature an iPad where visitors can vote on what will be displayed from month to month. “I think we’re starting with the Prince Mongo poster,” Abdalla notes with a mischievous grin.

Young Memphians have built one corner of the exhibit. “The education department’s installing these decorated lockers on one wall. We worked with different schools around the city to make lockers designed around the themes of the exhibit. … And the top three exhibits from each category will be featured.” In addition, a special day of free admission on March 3rd will feature performers, and at the end of the month, the Pink Palace will host a symposium on women’s suffrage as part of a series tied to next year’s centennial celebration of that watershed moment.

The most intense community involvement may be in the exhibit’s presentation of the city’s future. Not only will visitors see a “Trace Your Memphis Journey” display, where they create their own connections between themes using actual thread, they’ll see what the city has in store for us in the years to come. As Carrico explains, “At one point, we were struggling with how to end the exhibit. And that’s when the idea came up to incorporate Memphis 3.0 and the city planning process into it. So if you follow the timeline, toward the end, you’ll end up with a display on the Memphis 3.0 Plan, looking at how that planning process is impacting where we’re going forward.”

And, at the behest of the UrbanArt Commission, two artists from the Memphis 3.0 community engagement process, Yancy Villa-Calvo and myself, will have work presented. From 2017-18, Villa-Calvo staged many pop-up events with a large, graphic map of the city, on which people could mark their favorite places, and even record vignettes about themselves. My project, dubbed ReMix Memphis, hosted similar events, all concerning people’s reactions to the sounds of the city. For this, Pink Palace visitors will be treated to a large video game console on which they can play sounds familiar to all Memphians, including trains, tornado sirens, and cicadas. And, in the spirit of the word clouds, they can note what sounds they associate with the city and drop their card in a slot.

Simultaneously with the exhibit’s opening, a SoundCloud link will present original works by Memphis musicians like IMAKEMADBEATS, cellist Jonathan Kirkscey, and others, who added music to ReMix Memphis field recordings, to create an eerie sonic journey through the city via 16 original tracks.

This, then was the perfect finale for the ambitious, cutting-edge exhibit. As Abdalla says, “I think it’s great that we’re a part of continuing that process that Memphis 3.0 started, like collecting the sounds, or Yancy’s asset mapping. It’s that continual message of, ‘Hey, this is not ending. The Memphis 3.0 district meetings may be over, but this is still something ongoing.’ It’s a great way to end everything.” Carrico adds, “Our hope is that anybody who comes in will see something that is powerful to them. Be it a picture or an artifact, they can see themselves in the story.”

Larry Kuzniewski

Larry Kuzniewski